‘O, Shrill-Voiced Insect’: The Cicada Poems of Ancient Greece

Classical poets loved cicadas so much they wrote odes to them.

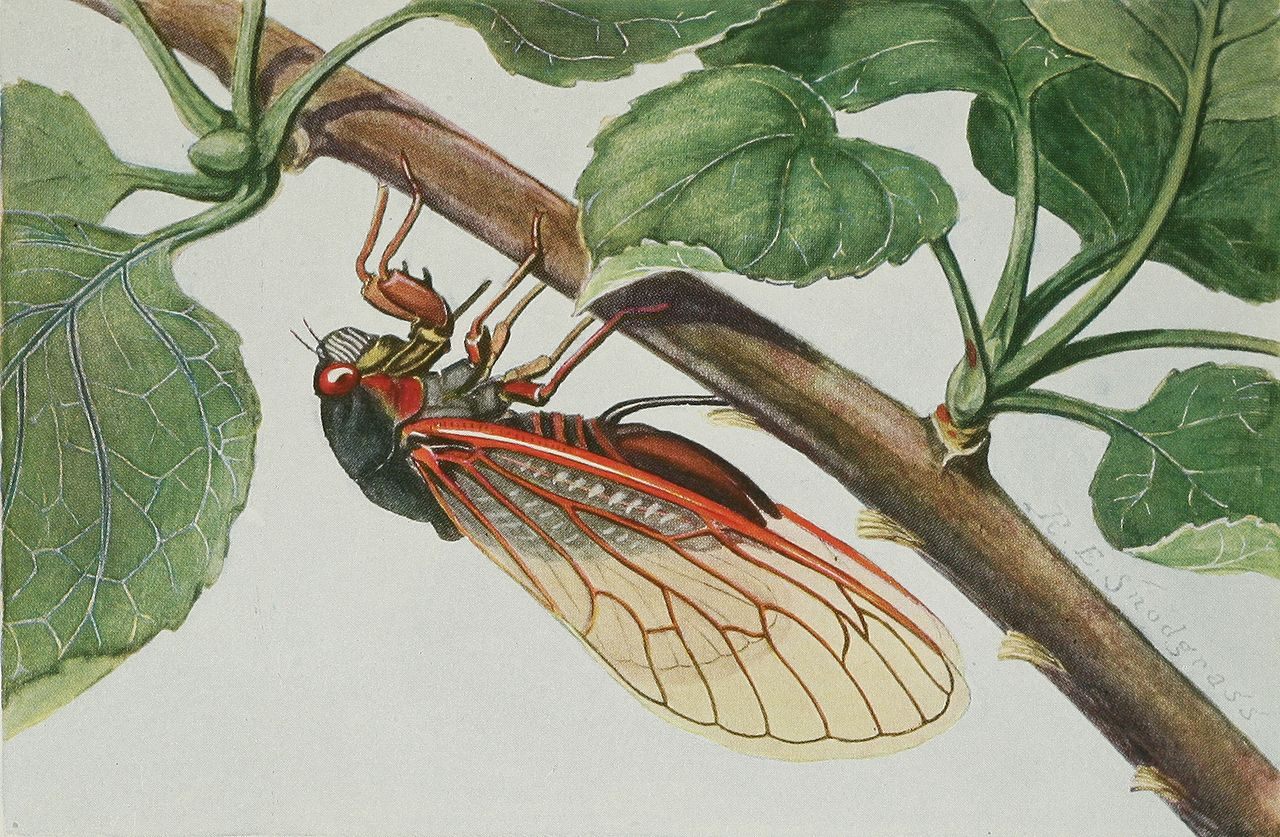

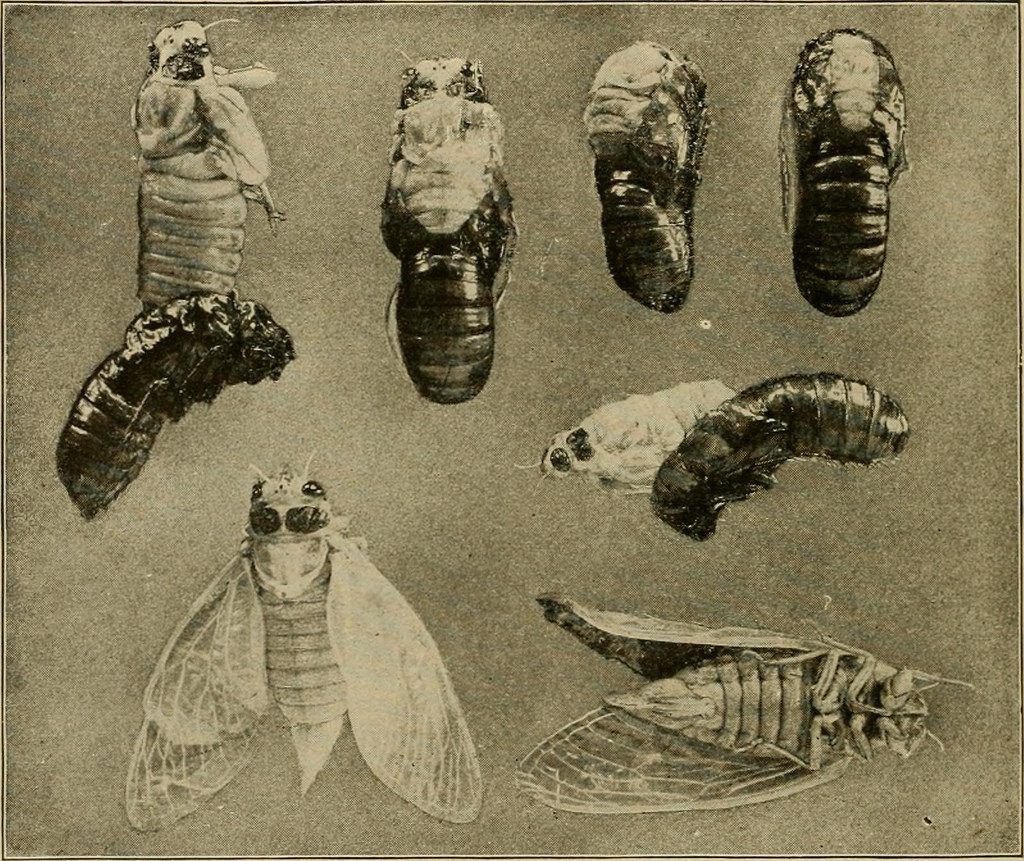

A Magicicada septendecim, a periodical cicada. (Photo: Public Domain)

This spring, after some 17 years beneath the ground, billions of cicadas announced their return with a cacophony of shrill chirps. Of course, we’re not the first to take take note of the winged, red eyed bugs; ancient civilizations lived with them, too. But, if you’re less than thrilled about the high-pitched, constant buzzing in your backyard, or the masses of cicada carcasses scattered across the sidewalk, ancient Greek poets would have said you’re on your own. They didn’t just observe these bugs; they admired them. They wrote cicada poems.

“O, shrill-voiced insect; that with dewdrops sweet,” begins an ode to cicadas by Meleager of Gadara, a first century B.C. Syrian-Greek poet:

“Inebriate, dost in the desert woodlands sing;

Perched in the spray-top with indented feet,

Thy dusky body’s echoing harp-like ring.

Come, dear cicada, chip to all the grove,

The Nymphs and Pan, a new responsive strain;

That I, in the noontide sleep, may steal from love,

Reclined beneath the dark overspreading plane”

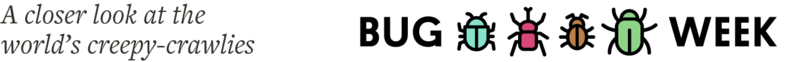

The sounds of cicadas inspired Greek poets. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

For these entomologically inclined poets, cicadas symbolized death and rebirth, due to the bugs’ elongated and hidden life cycle. In ancient Greece as in the United States, cicadas spend their nymph stage underground; classical poets likely observed species that buried themselves for two to five years (some North American species have 13 or 17-year cycles) in alternating broods.

When they do emerge from the earth, the scene is dramatic. Nearly all at once, swarms of insects shed their exoskeletons in identical, crispy heaps, cling to trees, and make a long, distinctive buzzing sound, which comes from the male’s hollow lower torso rattling against specialized muscles like a drum. Americans find it eerie. Ancient Greek poets, like Meleager and Virgil, thought this was beautiful.

But when the sun’s bright beams fierce thirst in spire,

And shrill cicada all the woodlands tire,

Then, to deep wells and spreading waters guide,

Or oaken troughs by living rills supplied–Virgil’s Georgic III 29 BCE

A 3rd century mosaic showing the poet Virgil. (Photo: Giorces/CC BY-SA 2.5)

Rory Egan, a historian of Greek culture and language, delved into cultural entomology in his paper “Cicadas in Ancient Greece, Ventures in Classical Tettigology.” Due to faulty translations in the past, some academics had thought that classical poets wrote of grasshoppers or locusts, but historians, including Egan, have since established that the Greeks were in fact struck by cicada fever.

According to Egan, the ancient Greeks not only loved the emergence of cicadas from the ground, and their characteristic song, but also believed they survived only on dew and air. The connection between the red eyes and husked bodies of cicadas and notions of love and piety make sense in some ways—their shrill sound is, in fact, a love song, meant to attract females to males. And you can bet that early Greek poets made that connection in strange ways.

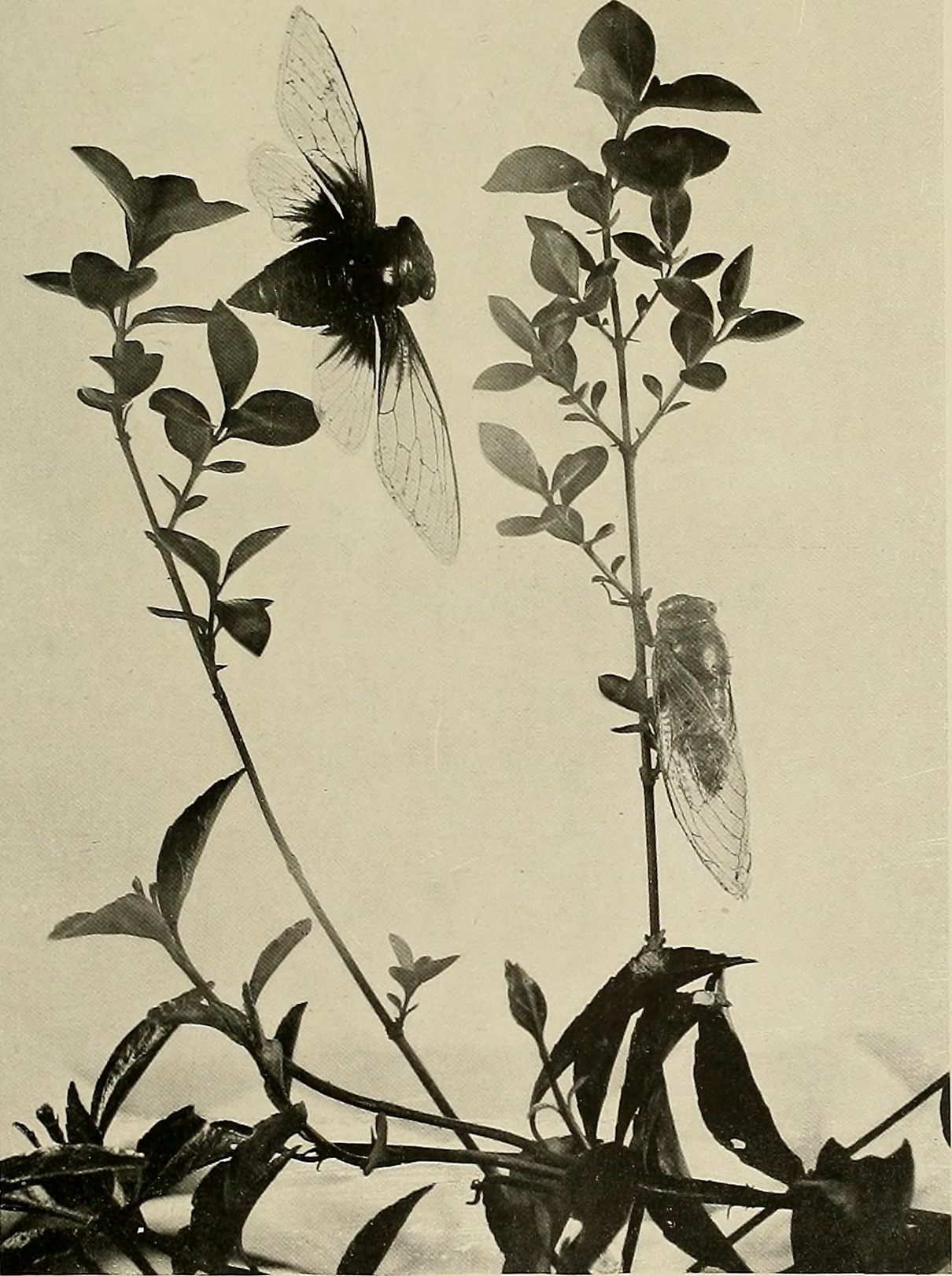

In the story of Tithonus, a good-looking young man is granted immortality by his lover, Eos. Unfortunately for Tithonus, the goddess is unable to give him eternal youth along with eternal life. Over time, his body ages far beyond normal human senescence; he “babbles endlessly, and no more has strength at all, such as once he had in his supple limbs.” So Eos takes pity on his withering body, and turns her lover into an insect, who then laments his luck by singing in the afternoon. In all accounts he becomes a cicada.

Eos pursuing Tithonus on an oinochoe. (Photo: Public Domain)

The cicada-love connection is taken to another symbolic level by Plato. The dialogue Phaedrus, a back and forth conversation about, among other topics, erotic love and how to use rhetoric, invokes the bulging-eyed bugs three times. In it, Socrates and Phaedrus walk to a tree that has anti-aphrodisiac effects, and Socrates can’t help but remark how, “By Hera”, the place they chose to sit was beautiful:

“Feel the freshness of the air; how pretty and pleasant it is; how it echoes with the summery, sweet song of the cicadas’ chorus!”

Not only did cicadas represent “various sexual and erotic connotations” as Daniel S. Werner notes in Myth and Philosophy in Plato’s Phaedrus, they were connected to the Muses themselves, as her agents on Earth. Socrates continues, saying: “I think that the cicadas, who are singing and carrying on conversations with one another in the heat of the day above our heads, are also watching us.” Later, he explains the cicada origin story:

“The story goes that the cicadas used to be human beings who lived before the birth of the Muses. When the Muses were born and song was created for the first time, some of the people of that time were so overwhelmed with the pleasure of singing that they forgot to eat or drink; so they died without even realizing it.

It is from them that the race of the cicadas came into being; and, as a gift from the Muses, they have no need of nourishment once they are born. Instead, they immediately burst into song, without food or drink, until it is time for them to die. After they die, they go to the Muses and tell each one of them which mortals have honored her.”

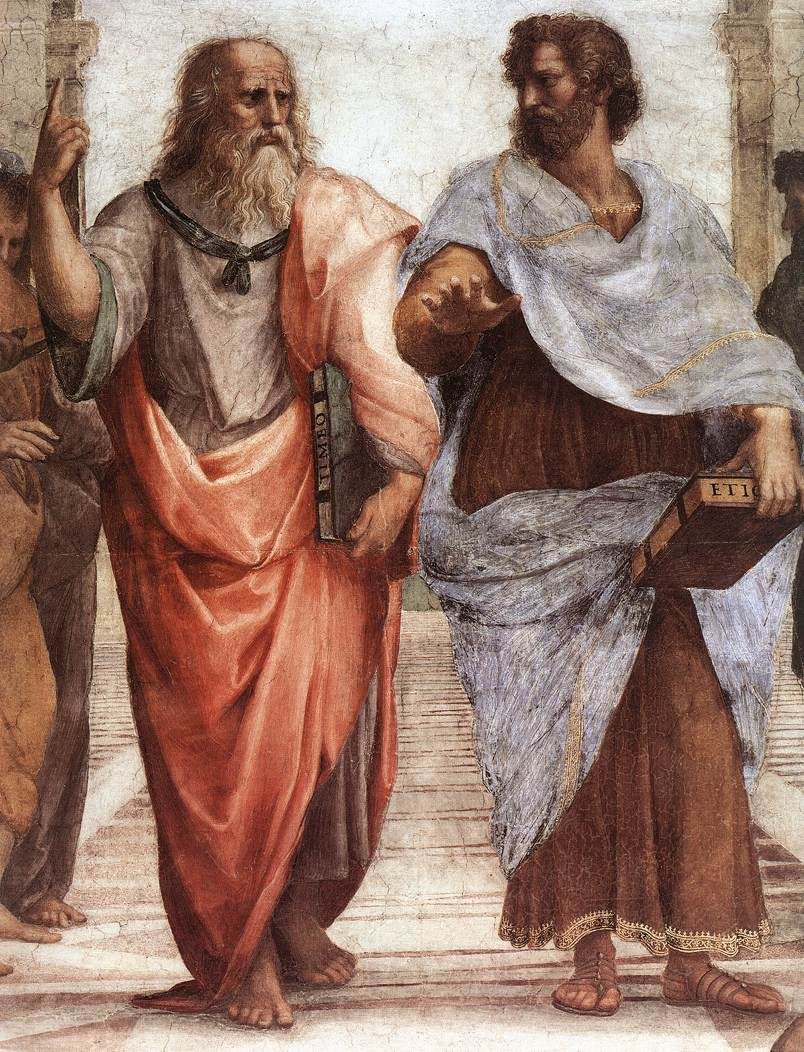

Plato (left) and Aristotle (right) in Raphael’s The School of Athens. (Photo: Public Domain)

Of course, the connection between life and death was also bridged by classical poets—the cicada, though buried in the ground, doesn’t die. In The Oxford Handbook of Animals in Classical Thought and Life, Gordon Lindsay Campbell writes that some cicada poems were “possibly prompted by genuine emotion,” in part because these insects were loved, and even kept as pets.

Anyte of Tegea, a female poet who lived around 300 B.C., explored the emotional significance and symbolism of insects in a short epitaph poem called “A Locust and A Cicada.”

“Myro, a girl, letting fall a child’s tears, raised this little tomb for the locust that sang in the seed-land,

And for the oak-dwelling cicada; implacable Hades holds their double song.”

The earliest reference to the cicada, according to Egan, arrives in the Iliad. The celebrated epic poem is set during the Trojan War. The abducted Helen of Troy is heartbroken, remembering her former husband, family and life. She approaches the tower that marks the entrance to the seized city, and the poem describes the old men who speak to her:

“They sat there, on the tower, these Trojan elders,

like cicadas perched up on a forest branch, chirping

soft, delicate sounds. Seeing Helen approach the tower,

they commented softly to each other—their words had wings”

In some translations, writes Egan, the voices of the men are even described as “lily-like”, something that has perplexed scholars; Egan believes this is a misunderstanding of an ancient Greek word associated with “dewiness”, which might just mean their voices croaked.

Stages of a cicada. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

While contemporary fans have created cicada orchestras and apps that play the cicada’s shrill song, our society’s admiration of the bug seems to be no match for the classical poets of Greece.

In the spirit of giving the cicada its deserved reverence, a poem from the collection Anacreontea (translated by Egan), which appeared between 1 B.C. and 6 C.E., probably says it best:

“We know that you are royally blest

Cicada when, among the tree-tops,

You sip some dew and sing your song;

For every single thing is yours

That you survey among the fields

And all the things the woods produce.

The farmers’ constant company,

You damage nothing that is theirs;

Esteemed you are by every human

As the summer’s sweet-voiced prophet.

Muses love you, and Apollo too,

Who’s gifted you with high pitched song.

Old age does nothing that can wear you,

Earth’s sage and song-enamored son;

You suffer not, being flesh-and-blood-less–

A god-like creature, virtually.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook