The 1903 Parrot Academy That Taught Birds to Speak Using Phonographs

In three languages!

Only the most prestigious pupils could enroll in the Philadelphia Phonograph School of Languages for Parrots, which in 1903 was said to be “the only institution of its kind in the world.” It boasted over 100 feathered graduates that “could pronounce all kinds of sentences and phrases” and speak three different languages (English, French, and German).

One of the school’s most distinguished alums was a parrot that, in the morning, could tell the children in its house it was time for school and, at night, could “ask them, with a knowing look, if they have mastered their lessons and express the hope that they have been good scholars.” This bird belonged to an unnamed famous actress.

A woman named Mrs. Hope—the school’s founder and only teacher—started the academy because her husband, a bird seller, found that he could make 10 times the profit on a single parrot if it could talk. She wanted in.

“It was because the demand for good talkers was one which Mr. Hope could not always supply that Mrs. Hope, who is his wife, established her school,” The Strand Magazine wrote, identifying only the male Hope by first name.

Mrs. Hope’s Philadelphia school soon sparked a revolution in parrot pedagogy. Previously, the norm was for a professor to hide behind a curtain—seeing a person proved too much of a distraction for the birds—and repeat the same phrase hundreds or thousands of times, a process that Hope called “monotonous and tiring.” But Hope had an epiphany: rather than endlessly repeat “Pretty Polly,” she could instead make phonograph records and play those on loop.

“I tried this upon eight parrots and the success was beyond my expectations,” she said. The Strand Magazine article noted that those parrots “were declared to be the finest talkers in Philadelphia” and each sold for approximately £20 (roughly £2,000, or $2,500, today).

The birds were such a hit that Hope’s husband began boasting of them in the press. To one publication, he described how the school had trained a parrot for a soap company, Apple Soap, to squeal at customers, “Buy Apple Soap,” and “Apple Soap Forever.” The goal was for customers to heed the advice of the feathered employees and purchase the product. This was, he proudly declared, the future of advertising.

As news of Hope’s successes with phonographs spread, other parrot owners began requesting that Hope give speech lessons to their birds. She agreed; for a full school term, she would teach any bird to talk for the price of £8, though most customers opted for the shorter, 10-shillings-per-week option. Luckily, tuition covered room and board for the birds.

As of September 1903, the school had enrolled 20 students.

Arthur Conan Doyle himself may have memorialized the prestigious school in The Adventure of Black Peter, also published in The Strand Magazine in 1904, a year after the Philadelphia Phonograph School of Languages for Parrots feature was published. A throwaway line at the beginning of the book mentions the arrest of a “notorious canary-trainer.”

“In this memorable year ’95, a curious and incongruous succession of cases had engaged [Holmes’] attention,” he wrote, including “his arrest of Wilson, the notorious canary-trainer, which removed a plague-spot from the East-end of London.”

The meaning of “the notorious canary-trainer” has been the subject of much debate, with many fans wondering whether “canary” might be a euphemism of some kind, but one theory suggests that Holmes was in fact inspired by the Philadelphia parrot academy.

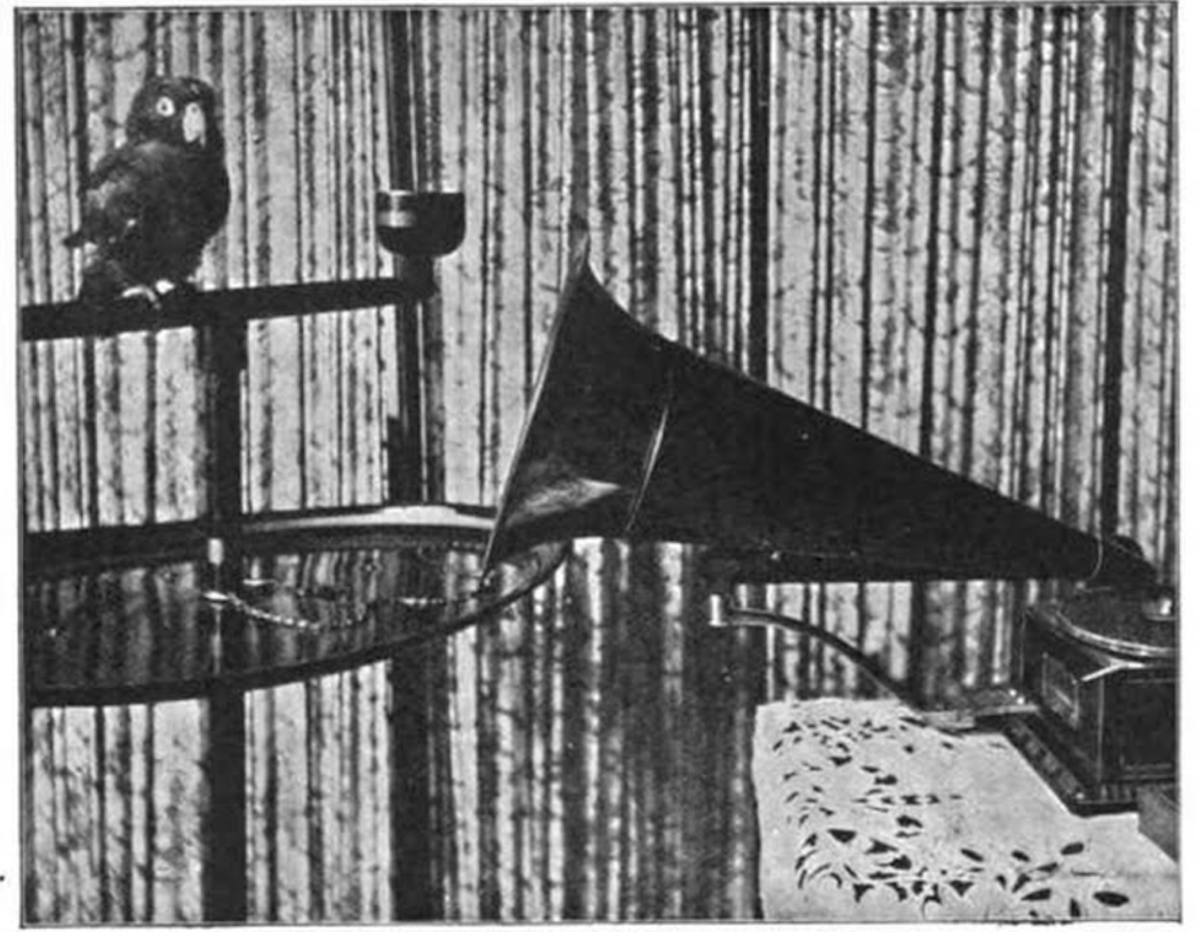

When the Strand Magazine journalist visited the Philadelphia school, he described eight parrots sitting in a room, staring intently at a phonograph that repeated, “Pretty Polly, Pretty Polly.” He wrote: “The birds were listening attentively, and now and then one of them would stammer, ‘Pree-pah,’ ‘Pree-pah.’” They kept on repeating the words until they got them right.

“Those parrots will hear that phrase for a week,” Hope remarked. “It takes the average bird a week to learn one sentence. Only one lesson is given a day, and it lasts half an hour.”

Then the pair visited The Philadelphia Phonograph School of Languages for Parrots’ “star pupil,” whose valedictorian status had earned him a room all to himself. There, he was practicing “what is believed to be the longest speech ever mastered by a parrot”:

Yankee Doodle went to town

A-riding on a pony.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook