The Slowly Expanding World of Pet Deathcare

From traditional burial to taxidermy.

The road to Bubbling Well Pet Memorial Park in Napa, California, follows a range of twists and turns up a rocky, sparsely vegetated hillside. Eventually, a row of trees shading a series of sweeping glens appears, along with a pair of imposing gates. At first glance, Bubbling Well—which was immortalized in the 1978 Errol Morris film Gates of Heaven and features a burbling fountain to back up the name—looks like an ordinary cemetery, but a closer look reveals the graves are actually for cats, dogs, the occasional rabbit, and a few other species.

I came to Bubbling Well to explore the wide, and growing, world of pet death care. According to the American Veterinary Medical Association, some 30 percent of U.S. households have cats, and 36 percent have dogs—that adds up to a lot of animal remains every year. Pet guardians may spend time thinking about where their pets go when they die on a more metaphysical level, but the question of what happens to the remains of Fido and Fluffy at the end of their lives is one that’s been vexing humans for millennia.

“Disposition,” as the industry euphemistically describes what to do with the body, has evolved into a large industry that will bury or cremate your pet, sell you a headstone or urn, and even outfit your animal with a lavish casket. For some grieving pet owners, the combined costs can climb into the thousands—though for most, still below the $7,000 to $10,000 median human funeral cost. But while the options were once limited to burial in a backyard or abandonment at the vet’s for disposal, pet owners now can access a spectrum of services that rivals—and sometimes exceeds—those available to humans.

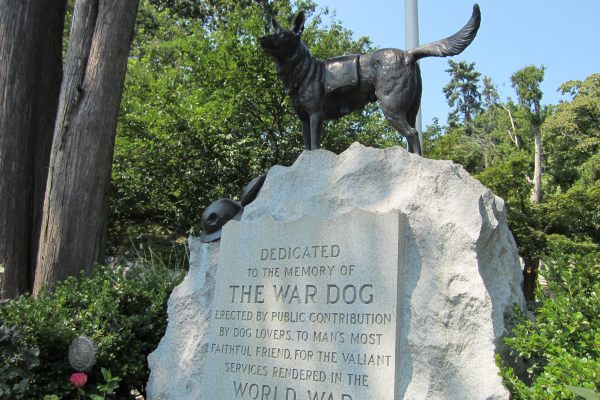

Burial is certainly the most traditional of options, one that has a long history in the human-animal relationship. The oldest known pet burial is a 14,000-year-old grave in Bonn-Overkassel in Germany that contains the remains of two humans and a domesticated dog. But growing urbanization has made backyard burials more unusual, especially with many people moving house frequently and not wanting to leave the late Lassie behind.

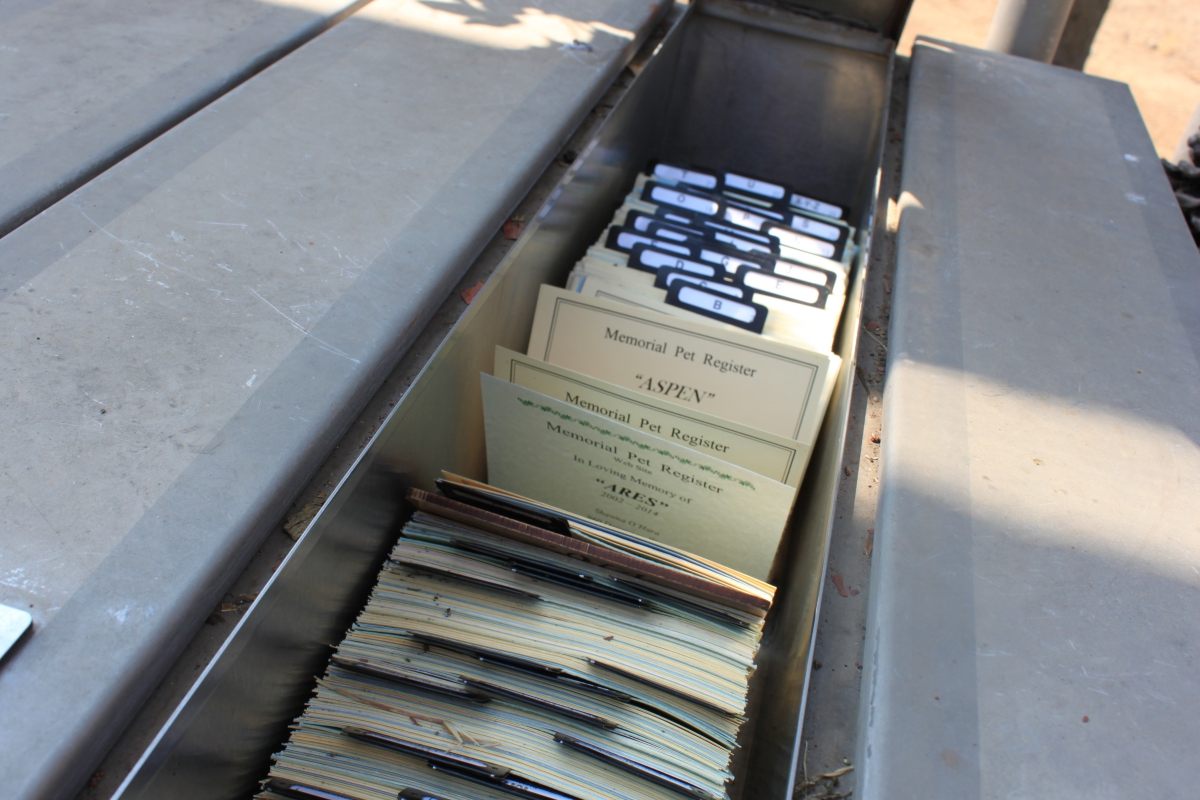

The response: pet cemeteries. In the United States, Hartsdale Pet Cemetery, the oldest pet cemetery in the country, has been home to variety of deceased animals, including a lion cub, since 1896. But purchasing a plot for your pet in one of nearly 700 pet cemeteries across the United States is just the beginning.

Perusing pet headstones at Bubbling Well reveals that some families spend thousands of dollars on elaborate laser-etched headstones, while others opt for simple handmade markers. Many of those headstones are bedecked in flowers, and the remains underneath may be shrouded in plastic or fabric, or encased in wood, metal, or biodegradable caskets. Embalming, while a popular option for human funerals, is not as common when it comes to animal companions, according to Donna Shugart-Bethune, Executive Director of the International Association of Pet Cemeteries and Crematories. This is partly because of cost and partly because many facilities aren’t equipped to perform the process.

Since cemetery plots can cost hundreds of dollars, some pet guardians turn to the less expensive option of cremation. There are two primary kinds of cremation: “group,” wherein the ashes of a single animal are mixed with the ashes of others, or the more pricey “private,” which ensures the only ashes you receive are the ashes of your companion.

But here lies another parallel to the human death industry. When people started turning to cremation as a low-cost option for their human loved ones, the industry pivoted to catch up with elaborate urns, costly columbarium niches, and delightfully kitschy “memorials”—so it should come as no surprise to learn that the pet funeral industry has done the same. These days, a grieving guardian can store their beloved pet’s ashes in a German Shepherd-shaped urn, a statue of an unsettlingly dyspeptic-looking bronze cat in a basket, or a ceramic paw-print plaque.

If the pet funeral industry is following human trends with respect to “traditional” disposition, it also appears to be taking cues from the growing alternative death movement. Humans are changing the way we think about death and dying, and the result is a new approach to death care that’s spilling over into animals, too.

When it comes to burial, pets—or rather, their guardians—can opt for the natural route if they don’t like conventional, manicured cemeteries. So-called “green cemeteries,” designed primarily (though not exclusively) for humans, only accept unembalmed bodies in shrouds or caskets made from simple, biodegradable materials, like willow. Graves are shallow, allowing remains to break down more quickly, and the cemetery is left untouched, without landscaping. Some green cemeteries have a separate pet section, while others allow for “whole family” burial, mingling humans and pets together just as they have been for thousands of years.

John Wilkerson of Glendale Memorial Nature Preserve in Florida explains that he and his family started the green cemetery as a way to retain family land, but didn’t think to bury animals until a customer brought it up. At cemeteries like Glendale, mourners are encouraged to get involved, digging graves and participating in as much of the process as they’d like, whether they’re burying pets or people.

At Resting Waters in Seattle, operators Joslin Roth and Darci Bressler offer yet another option—and one that hasn’t widely extended to humans yet, thanks to regulatory challenges. Instead of traditional burial or cremation, they perform alkaline hydrolysis (AH), sometimes known as “aquamation.” Bodies are dissolved in a chemical solution, yielding water and hard tissue that can be ground down, just like cremated remains. The process, Roth says, “is very gentle,” acting effectively like an accelerated version of what happens in nature. She sees it as the future of both human and animal death care, if they can overcome the stigma—a situation akin to that faced by cremation when it was first introduced on a large scale.

Thanks to the limited regulations surrounding pet death, those looking for unusual ways to memorialize a loved pet have a lot more options than people looking to do the same for humans. Some pet guardians opt for taxidermy or freeze drying, or even articulation of full or partial skeletons.

Taxidermy and skeletal articulation draw upon practices used for hundreds of years to preserve animal remains, usually in the form of anatomical specimens or hunting trophies. Companies like Precious Creature in Southern California, though, specialize in caring for pets, a nod to a market of deeply attached pet owners.

Freeze drying, yet another option, preserves whole bodies by bringing them to very low temperatures and low pressure, forcing frozen water to turn to gas over a period of weeks or months. Companies promising a meticulous preservation process give a new meaning to never letting go, likewise reflecting a sea change in the way we think about companion animals.

As I leave Bubbling Well, I see an open grave. Two adults and a child stand awkwardly, a large Golden Retriever panting by their side, as cemetery employees carefully lower a cloth-wrapped body into the hole. I hear snatches of conversation on the breeze and the child kneels, dropping something in. Though the business of pet death has changed, after thousands of years, we’re still leaving Fido with something to play with in the afterlife.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook