The Quest to Rediscover New Zealand’s Lost Pink and White Terraces

A German diary from 1859 might point the way to a geothermal wonder buried by a volcanic eruption.

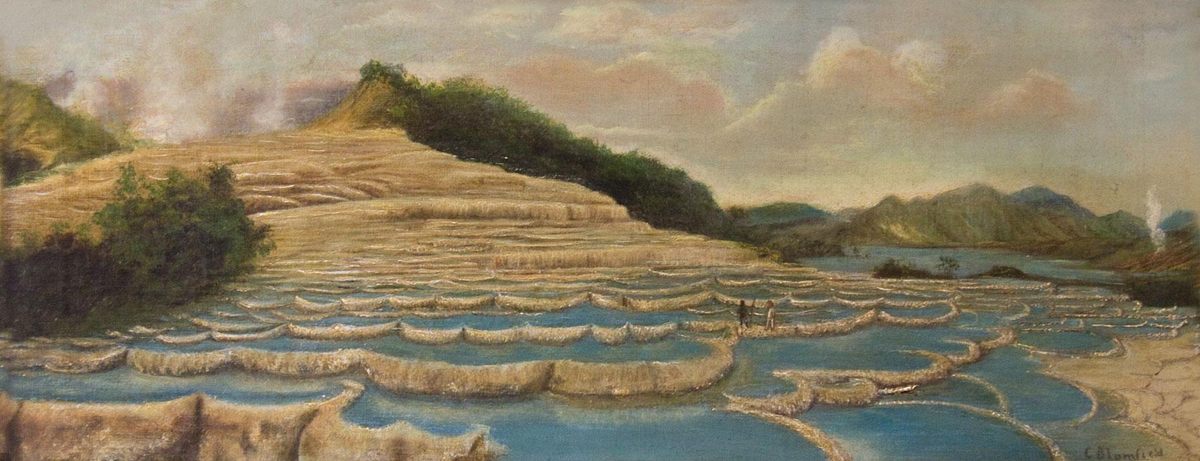

Roughly the size of a city block and up to eight stories high, the Pink and White Terraces of New Zealand were one of the top tourist attractions in the British colony during the 19th century. Visitors came from around the world to admire the dramatic, colorful, cascading formations—formed by the mineral-rich waters of a geothermal spring—on the shores of Lake Rotomahana, at the foot of Mount Tarawera on the country’s North Island. Willy Bennett saw the terraces as a child and described them for a New Zealand radio program in 1954: “The White Terraces were not actually white, but their silica coating, tinged here and there with the palest of pinks, gave you the overall impression of old ivory tinted a faint yellow. Likewise, the Pink Terraces, which ranged from a rich salmon pink to a soft rose, were themselves, in places, almost as pale as the White.”

It wasn’t just the color of the terraces that attracted admirers to Lake Rotomahana’s shores. “The color and sparkle of moving water constantly spilling over them gave the terraces a liveliness and almost a personality of their own. Truly, they were a thing of beauty and a joy forever for the few who saw them,” recalled Bennett. He was just 12 years old when Mount Tarawera erupted in June 1886.

“I was no sooner out of my bed than I was on the floor, the earthquakes were so severe that one couldn’t stand unless one held onto something,” he added. “As soon as we got outside, we could see the trees and buildings swaying to and fro, and it was rumbling like long-distant cannons going off.” The Tarawera eruption lasted about five hours, buried the region in ash, and dramatically reshaped the landscape. A 10.5-mile fissure cracked open along the mountain’s lava domes. The original Lake Rotomahana at the base of the mountain was “blown sky-high.” The Pink and White Terraces were thought lost forever.

The fate of the terraces—blown to bits or buried or something else—is a mystery, well and truly lost. The only survey of the terraces before the eruption, completed in 1859, wasn’t rediscovered until 2010, when a research librarian found it in a diary in a family archive in Switzerland. Even with that, the precise locations of the terraces is unknown, which has meant that no one could determine whether they survived the eruption. Finally, 131 years after the Tarawera eruption, there’s new hope the terraces can be rediscovered, and perhaps even resurrected, thanks to that 1859 diary.

The diary belonged to Christian Gottlieb Ferdinand von Hochstetter, a German geologist who traveled with the Austrian Novara voyage that set out to circumnavigate the globe. When the expedition reached New Zealand, Hochstetter led a surveying expedition on a nine-month tour of the British colony. “At the time of Hochstetter’s survey in 1859, very little of the inland areas of the North Island of New Zealand had been surveyed,” research librarian Sascha Nolden told Atlas Obscura in an email. “Surveys tended to be limited to populated areas earmarked for subdivision and the establishment of settlements. By the time Mount Tarawera erupted in 1886, New Zealand had been completely mapped, but there were vast areas that were not surveyed in any detail.” The eruption completely altered the landscape, changing the size and shape of Lake Rotomahana and burying geothermal features. Hochstetter’s diary, with the survey of the affected region, wound up far from New Zealand in Hochstetter’s family’s library in Switzerland, where Nolden rediscovered it.

Over 100 years later, New Zealand’s GNS Science agency (roughly equivalent to the U.S. Geological Survey) conducted a bathymetric survey of Lake Rotomahana. The surveys, conducted between 2011 and 2014, turned up evidence the agency said suggests the terraces are now located under the lake. “That’s what led me, in fact, to [propose a plan] in 2014 to operationalize their findings and lower the lake 40 meters and recover the terraces from where they stated they had found them,” says Rex Bunn, an independent researcher who developed an acute interest in the fate of the terraces. GNS Science suggested Bunn halt the project when it discovered there was a magma chamber under the lake, which could be affected by the movement of so much water.

Bunn was disappointed and shelved the plans, but as he was writing up the failed project he got in touch with Nolden, the librarian. When Nolden sent him the pages with the survey from Hochstetter’s diary, says Bunn, “it was one of the most exciting moments of my life. I knew that it was a survey and that it had compass bearings that we could use to finally establish the locations of the terraces.” He spent the next six weeks deciphering the diary’s handwritten German notes with Nolden. The team eventually matched the diary’s survey points with the modern landscape, detailed in a paper for the Royal Society of New Zealand’s journal, published in June. It turns out that draining Lake Rotomahana is entirely unnecessary—according to Hochstetter’s survey, the terraces may be located on land, under 3o to 50 feet of volcanic ash.

The next step will be confirming the terraces survived there before attempting an expensive excavation. To do that, says Bunn, he’ll lead a team on an expedition to locate the terraces using ground-penetrating radar (GPR) in the near future. “If the GPR does show encouraging imagery, I would think it’s almost inconceivable that the next step would not be taken,” says Bunn. If they can confirm the locations of the terraces, Bunn plans to collect core samples from each to be analyzed by a chemist. It can then be compared to a known sample collected before the eruption, which Bunn says suggests the famous colors were the result of antimony and arsenic sulfides in the spring’s water. A match will likely mean the team will move on to excavating the terraces under archaeological supervision.

Even if Bunn’s team finds, identifies, and excavates the terraces, there’s no guarantee that they will look anything like the ones lost in 1886. “Geothermal springs of course vary over time, like volcanoes, due to crustal shifts and so on, and it’s almost certain that the hydrothermal springs that powered the Pink and White Terraces are no longer functioning, given time and also the 1886 Mount Tarawera eruption that transformed the landscape,” says Bunn. “Whether the terraces are intact to a greater or lesser extent on those locations can only be answered by excavation, ultimately.”

He can only speculate about the future of the terraces. Restoring them, he says, is “a wish list at this stage. It might even prove to be a pipe dream. It may or may not be possible and it’s well down the track.” Before that can happen, all his planned work must go through the local Maori tribe that owns the land. But Bunn is optimistic that Hochstetter’s survey is accurate, and that history will be made. “I think we’re probably closer to finding the Pink and White Terraces than any other research group in the last 131 years.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook