What Planned Parenthood Taught WWII Veterans About Birth Control

“The step-up in your pulse when a nifty number looks your way isn’t love. That’s sex, mister.”

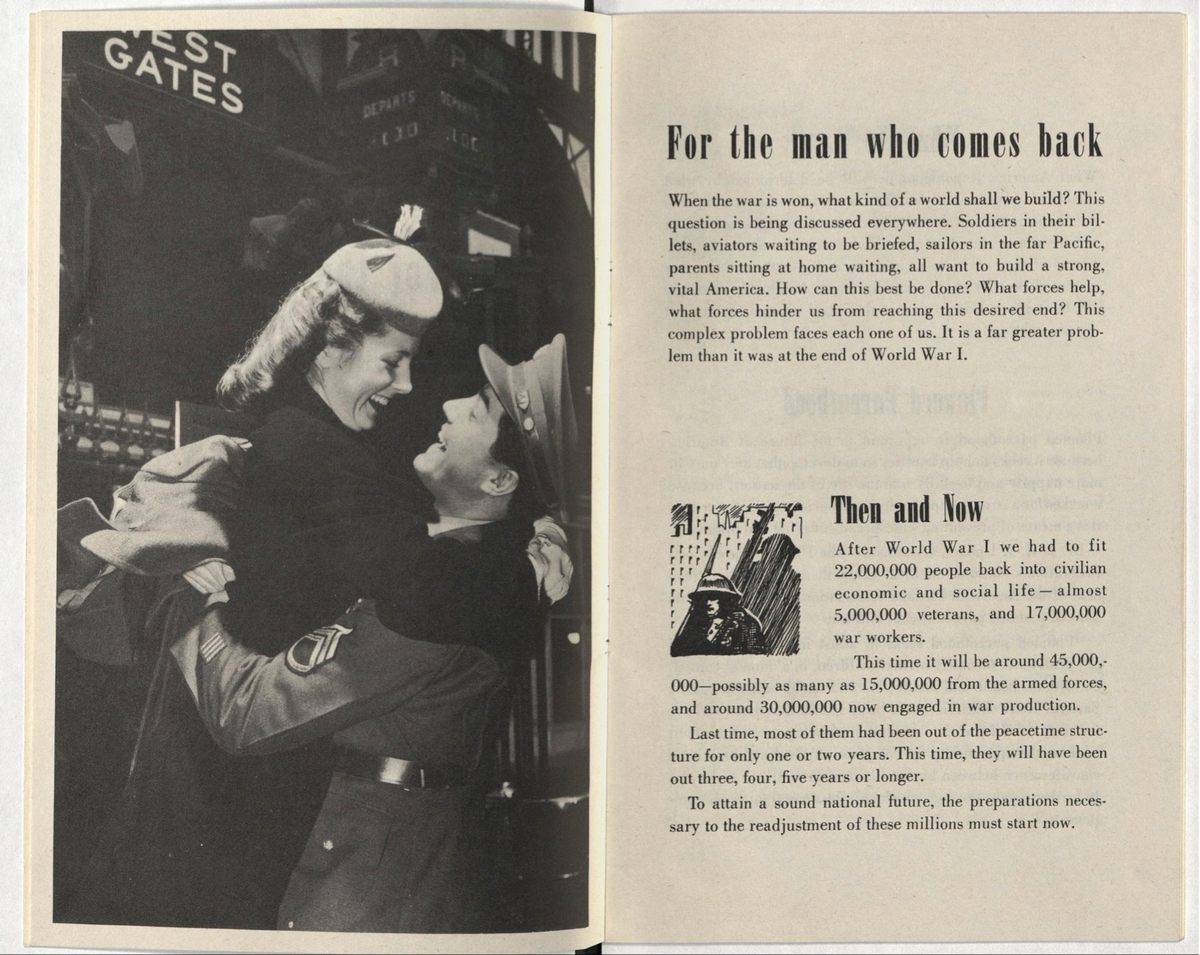

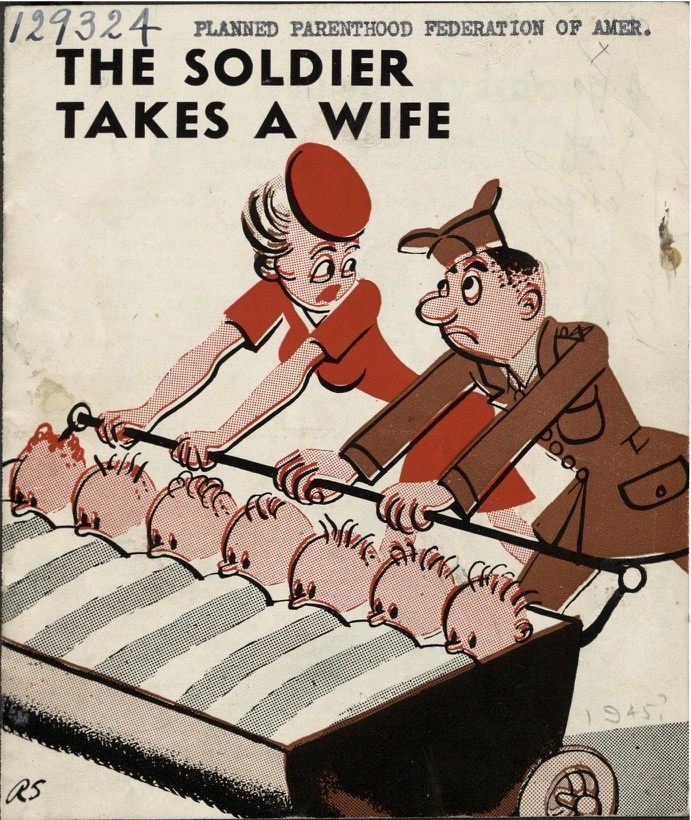

When soldiers returned from World War II in the mid-1940s, the Planned Parenthood Federation of America was ready for them. With educational programs and materials, such as the pamphlets “The Soldier Takes a Wife” and “For the Man Who Comes Back,” the organization targeted long-separated couples and men eager to spend time with real-live American women instead of paper pin-ups. Whether a wife, a sweetheart, or a dedicated correspondent, one pamphlet read, “you don’t need to be told, any one of them in the flesh is better than a million pictures on a wall.”

“Millions of our returning fighting men and servicewomen will come back with one thing uppermost in their minds,” stated another. What did these men and women want? “A home of their own and children to whom they can gave give the best chance of health and happiness.”

Although the birth control movement was started by radical feminist women who believed in liberation from childbearing, by the 1940s, the movement’s message had changed. In 1942, the Birth Control Federation of America changed its name to the Planned Parenthood Federation of America and began focusing on family planning and spacing out births, rather than women’s rights.

By the end of the war, the organization had “largely abandoned the women-centered approach of the earlier birth control movement,” writes Peter Engelman, in A History of the Birth Control Movement in America. This new message “appealed more to men and the male-dominated public health departments, hospital, legislatures, and government agencies that were integral to the future success of the movement.”

The pamphlets shown here, from the collection of the New York Academy of Medicine, were willing to talk frankly about sex (“The step-up in your pulse when a nifty number looks your way isn’t love. That’s sex, mister,” one reads), but they also promoted norms rather than rebellion, sexuality within traditional marriage, and having plenty of babies—at the right time.

In the decades before World War II, the birth rate in the United States had declined steadily, but after war, the national attitude toward childbearing shifted. “Procreation was one way to express civic values,” writes historian Elaine Tyler May in Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era. “Along with the baby boom came an intense and widespread endorsement of pro-natalism—the belief in the positive value of having several children.”

In its brochures, Planned Parenthood didn’t try to fight that tide. Instead, the organization focused its message on having kids at the right time, when a couple’s relationship and finances were strong. The organization also encouraged couples to space out their children, and let a mother’s body rest and recover between births. “Getting married and having a family is like a military campaign. It makes forethought, preparation and a certain amount of strategy,” the pamphlet “The Soldier Takes a Wife” advised men. “By planning and preparing for the birth of each child you and your wife can do much to improve its prospects for health and happiness.”

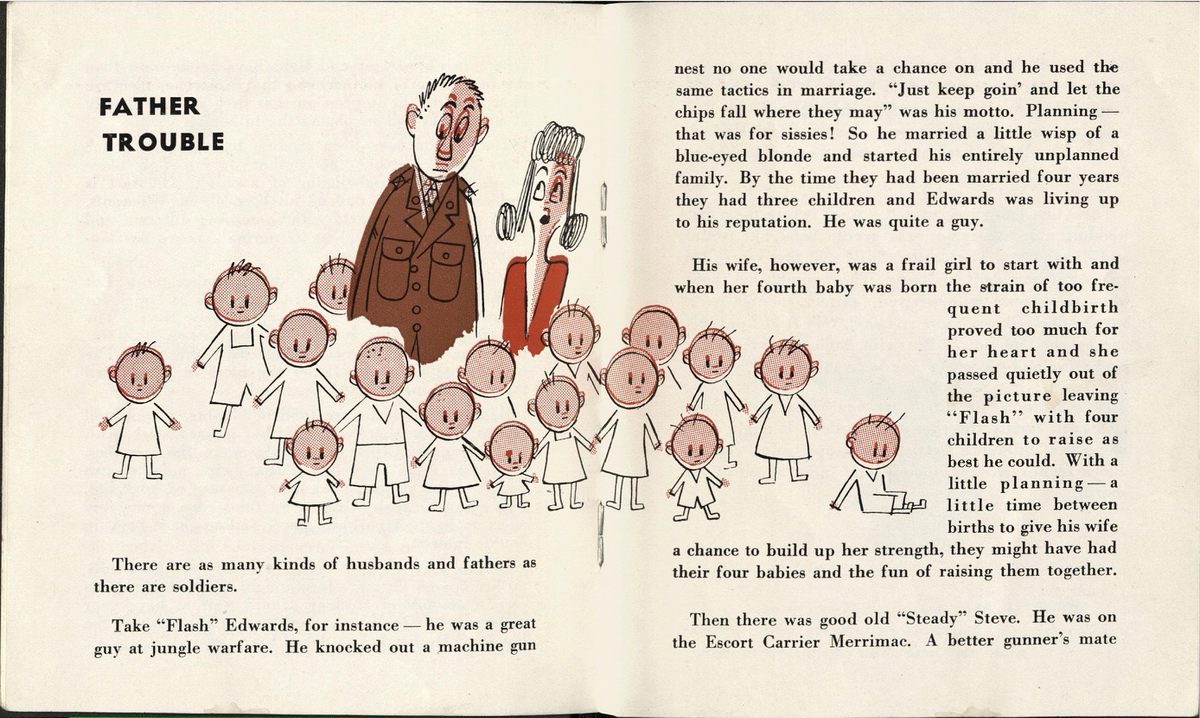

The pamphlet included scare stories about what would happen to men who didn’t follow this advice. “Flash” Edwards’ wife dies because she had too many kids too fast, and “Steady” Steve gets himself into financial trouble by failing to plan his family carefully.

The one vestige of Planned Parenthood’s more radical past was its emphasis on female sexuality. “Frigidity and unhappiness are often the natural results of selfishness or lack of appreciation by the man of his wife’s sexual needs,” the pamphlet advised. “Love-making among civilized peoples is a delicate art which can be attained only when the physical and emotional desires of both mates are realized.”

The organization spoke directly to men about this, too. “You can learn these things by sharing your wife’s feelings instead of just thinking of your own.” (The history of feminism and women’s issues in the 1950s suggests that few men absorbed this advice.)

Even female sexuality, though, was promoted in service of a greater goal—America’s bright future. “Mating may be the first objective of a marriage but two other goals—companionship and children are equally important,” Planned Parenthood advised. “Planned parenthood is important to the future of America because it seeks to help families so to develop [sic] that they may fit more happily and usefully into the life of the nation.”

Although birth control pioneers, including Margaret Sanger, who was still associated with Planned Parenthood at the time, fought the movement’s turn in this direction, this more normative message generally served birth control advocates well. “PPFA gave the birth control movement ‘a clean image,’ emphasizing not women’s rights, individual freedom, or sexuality, but as Scientific American noted, ‘the need of individual couples to plan their families and for the nations to plan their populations,’” writes May, the historian. “American society was certainly ready to accept birth control as a means of improving marital sex and family planning. But it was not ready to accept its potential for liberating sex outside marriage or for liberating women from childbearing to enable them to pursue careers outside the home.”

Information about and access to birth control didn’t stop the Baby Boom. The birth rate in America increased, and most couples in their 20s had multiple children. But it did, perhaps, limit its extent. Even if the postwar generation rushed to have kids all at once, those men and women did tend to stop procreating at a certain point. For these married couples, birth control didn’t keep them from having kids, or allow all women to pursue careers. But it did help couples choose the size of their families. Once they were ready to stop having kids, birth control was there to help.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook