The Two Best Dutch Anatomists of the 17th Century Hated Each Other

They had dramatically different ideas about how to depict dead bodies.

When two people share the same passion, that passion may draw them together, but almost as often it can drive them apart. Rival anatomists Govert Bidloo and Frederick Ruysch, who lived in the Netherlands in the late 17th century, were both innovators in a field that was, at the time, revealing the secrets of the human body as never before. Bidloo created a magnificent atlas of dissections that depicts the workings of the body’s muscles, organs, and bones; Ruysch was a showman who revolutionized the preservation of anatomical specimens and built cabinets of curiosities that drew dignitaries from across Europe. In the words of Daniel Margócsy, author of Commercial Visions: Science, Trade, and Visual Culture in the Dutch Golden Age, “The two anatomists despised each other.”

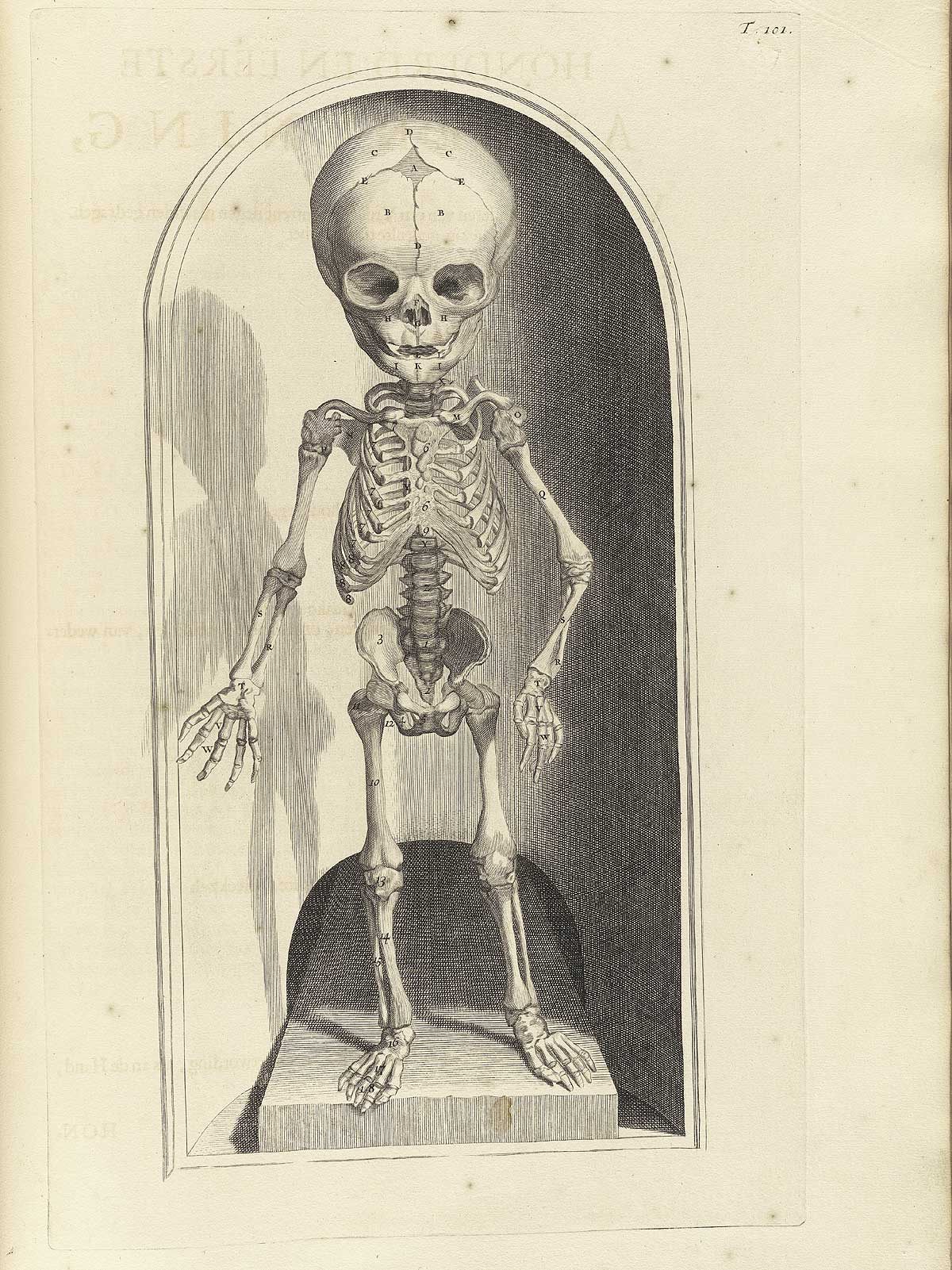

Though they shared a field, Bidloo and Ruysch diverged in their beliefs about almost every aspect of it. While Bidloo believed only printed images could accurately show the details of anatomy, Ruysch preferred displays of real skeletons and organs, suspended in preservatives. Bidloo offered realistic images of death that did not obscure the morbidity of this science. Ruysch created dioramas that added an element of art to his deceased subjects.

But this wasn’t an argument just about aesthetics. Each believed that the other was wrong about certain newly discovered details of anatomy, and each believed the other was misleading the public with false ideas.

In the 17th century, the study of anatomy was still cutting-edge science. Cadaver dissection became more acceptable and common, which led to a revolutionary new understanding of how the human body actually works. The circulation of blood was a relatively new discovery, for example. One of Bidloo’s accomplishments was demonstrating that nerves are not tubes that carry a liquid “spiritus” through the body, as blood vessels do. Some anatomists were revered for their abilities and insight, and were associated with the highest levels of society. For seven years, Bidloo served as personal physician to the English King William III of Orange, who was Dutch-born.

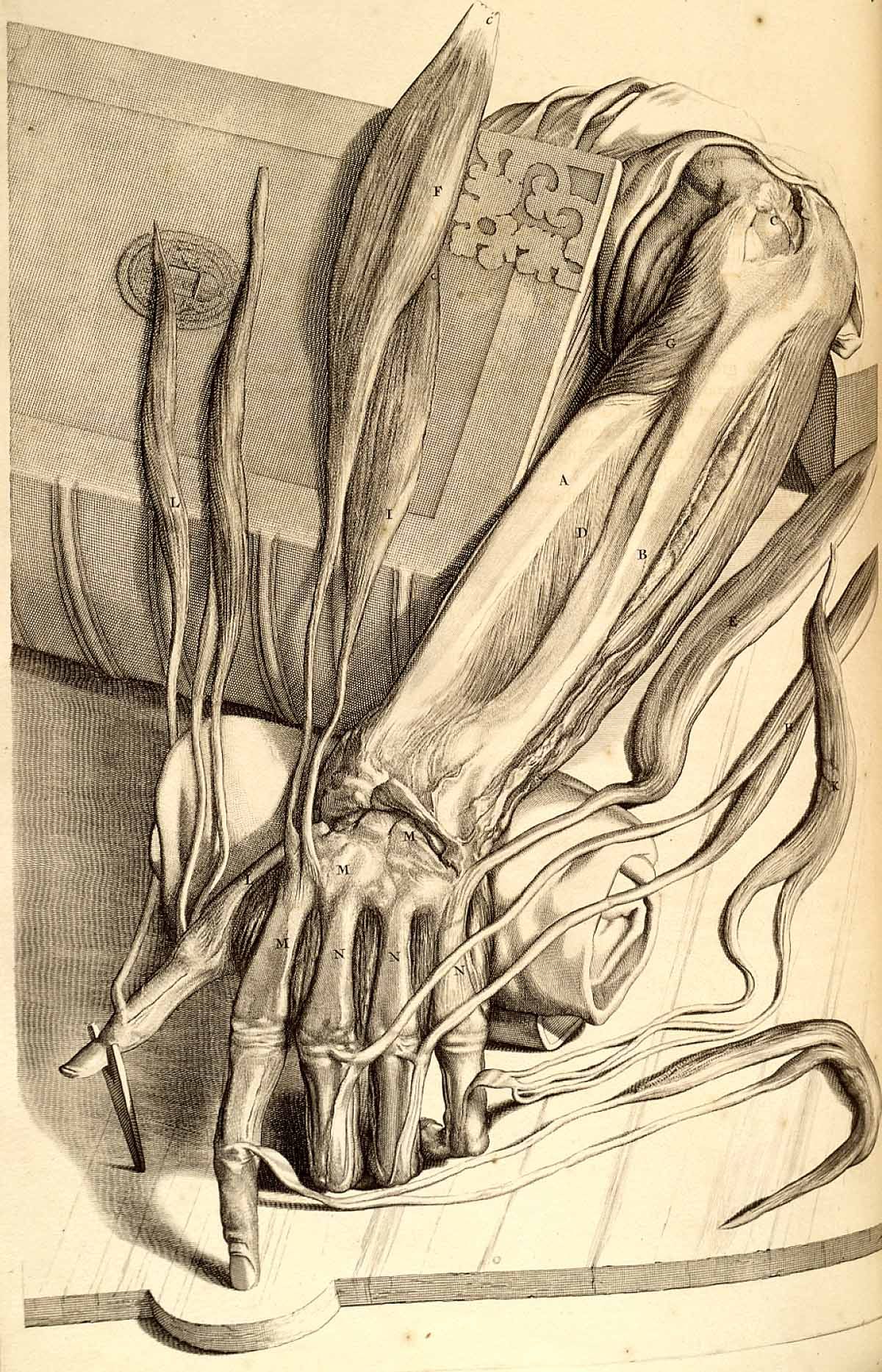

Anatomy as a practice and field of study lived at the intersection of art and science. Before Bidloo published his tome, anatomical illustrations tended to shy away from the grislier side of the work. Skeletons and skinned men, muscles exposed, were depicted moving through the world and demonstrating the workings of the human body as if they were alive. But Bidloo wanted to strip away that artifice. He “emphasized the deadness of the dissected body,” writes historian Rina Knoeff, in her article on “Moral Lessons of Perfection.”

The illustrations in his book, created by the artist Gérard de Lairesse, one of the most accomplished of his day, were based on 200 dissections, and they showed how the work was done. Skin and tendons are held back by pins and needles; in one image, a fly has landed on the dead flesh. Bidloo believed that living forms represent the epitome of beauty created by God, writes Knoeff, and that he should not try to reanimate these dead people through art. On the other hand, by offering images of the body and its parts from different angles, dissected using different techniques, he felt he could offer a more accurate and whole picture of how they worked.

Bidloo’s atlas was ground-breaking, but not wildly popular. Ruysch, on the other hand, knew how to attract a crowd. Based in Amsterdam, he led the city’s surgical guild, and became “the most active municipal anatomist in Amsterdam’s history,” historian Julie Hansen writes, as he performed 31 public dissections over his career. His greatest accomplishment as a showman, though, was the cabinet of curiosities he created to display the specimens he had gathered and preserved. “Venice et Videte!” he invited audiences. “Come and see!”

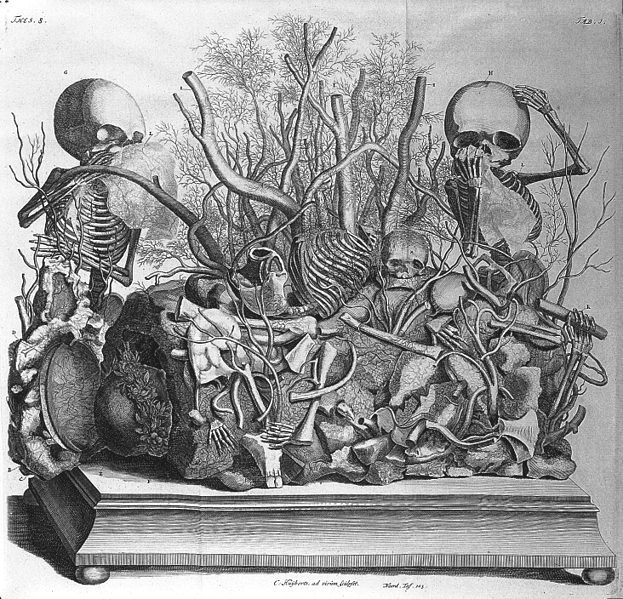

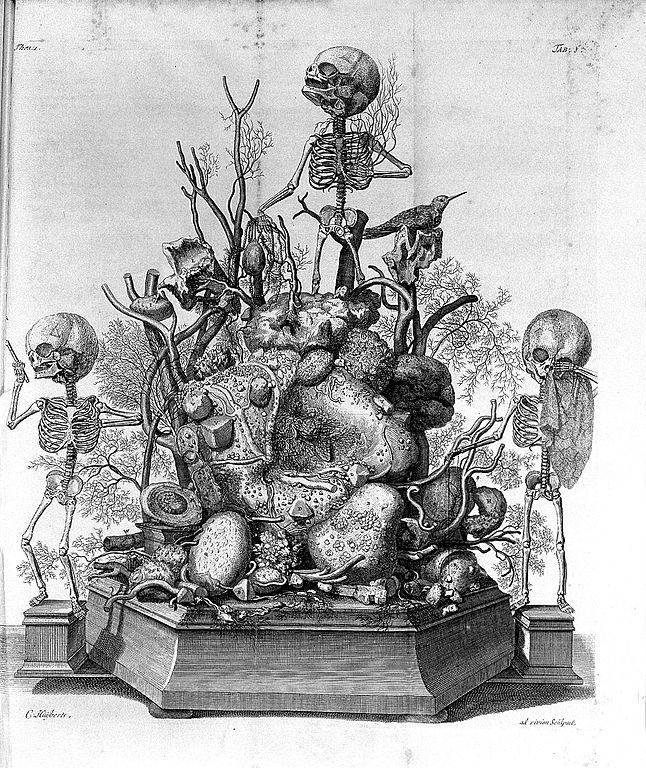

Using his collection of thousands of specimens, Ruysch created dioramas that combined skeletons, plants, and other specimens into fanciful arrangements. For him, most of these specimens did indeed clearly reveal the wonder of the human body—wonder was an important concept to him—and his displays helped people see the specimens in all their beauty.

Bidloo, predictably, disdained this aesthetic. The lace, the glass eyes, the false drama—he hated it all. (One can assume he was also bothered by the popularity of Ruysch’s work, which attracted crowds of enthusiastic intellectuals and nobles.)

If the two anatomists had different styles, though, they may not have been as divergent as either believed. “Bidloo’s stern aesthetic is just another interpretation of the same artistic trends that influenced Ruysch,” writes historian Elisabeth Brander. Ultimately, both were influenced by realism and still lifes in their efforts to communicate the true details of the human body—living or dead.

Bidloo and Ruysch did not end their dispute at aesthetics, though. Ruysch was an intellectual fighter, always ready for a scrap, and he challenged the accuracy of the medical information Bidloo presented. In a war of published pamphlets, they argued over the shapes of certain glands and the organization of the circulatory system. Ruysch needled Bidloo, and called him “shameless” and “the professor of impudence.” At one of his public demonstrations, Ruysch baited Bidloo to come forward and show that a cutaneous gland was oblate, as Bidloo had written. Ruysch held up the organ, which he said was clearly round. He also tried to show that a membrane around the brain is too thin and hard to dissect in any way that would prove that tiny blood vessels flow through it, as Bidloo’s illustrations depict.

There was a certain amount of artifice in even such live anatomy demonstrations, though. These were events, almost like fashion shows today, that were attended by interested dignitaries, who got the best seats. No one could see very well what was going on, and the other doctors were seated behind the dignitaries. The human eye could not detect all the subtleties of anatomy, and Ruysch knew this. His preserved specimens, too, though the finest of their day, were not exact representations: Some details were distorted in the process of preservation.

It’s true that the illustrations in Bidloo’s book include details that were not copied from anatomical specimens. Rather, they extrapolated from the anatomist’s knowledge of the body. This strategy, he argued, got at the ultimate truth of the body, which could never be captured with a single image or dead specimen. Through his knowledge and many images, he believed, he could provide a sense of how the body moves in life, a sense far more accurate than that of Ruysch’s decorated specimens.

At heart, these arguments were theoretical disagreements. Bidloo and Ruysch staked their reputations and their financial futures on these ideas. If the market is a measure of success, Ruysch won. His fame surpassed Bidloo’s, and while Bidloo had to fight the publishers of an English reprint of his book that used his illustrations but barely mentioned him, Ruysch sold his cabinet of curiosities for 30,000 guilders—a fortune—and set about making another. He understood what Bidloo did not: that realism could go too far. The way to get people to see his work with the clearest eyes was to make it just a little easier and enjoyable for them.

This story was inspired by an Atlas Obscura event at the New York Academy of Medicine. Join us in our ongoing series to learn about more amazing medical history in their rare books library.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook