Scam Reviewers Are So Crafty They Actually Deserve 4 Stars

(Photo: Artem Samokhvalov/shutterstock.com)

(Photo: Artem Samokhvalov/shutterstock.com)

You’re walking around the city with a group of friends. It’s 7 p.m., and you all have a similar urge to fill your stomachs with fish tacos and strong margaritas.

How do you decide which restaurant in which to park your derrieres and spend your hard-earned cash for a couple hours? Search reviews on Yelp or Google Reviews, of course.

In 2015, word-of-mouth reviews have gone viral. We’re more likely to trust a complete stranger’s favorable or unfavorable recommendation for restaurants, stores, products, and even dental hygienists, than our own instincts. If 100 random people review a meal, and it still has four stars, surely it’s bound to be pretty decent.

Or is it?

Online reviews are a serious driver of business. According to Bloomberg, favorable Yelp reviews can directly lead to a five to nine percent increase in revenue. More than that, over 90 percent of survey respondents in a Dimensional Research study indicated that their purchasing decisions were influenced by positive reviews. A 2012 Cornell University study found that, after a one-star increase in a hotel’s overall review score, that hotel could raise its room rate by 11 percent and wouldn’t scare away any new customers.

And online reviews are a serious business unto themselves. Yelp, probably the best known of the online review aggregators, has a market cap of $1.82 billion. Trip Advisor, the preferred travel agency for denizens of the internet, has a market cap of $10.91 billion.

So it’s certainly not chump change. But just how trustworthy are random strangers on the internet?

Surprise, surprise: not very. According to a 2013 study from the Harvard Business School (pdf), up to 16 percent of the Yelp reviews in the Boston area are fake. Totally, completely, fake.

Apart from getting into the ethics of posting fake reviews, the study indicates that the practice is motivated by simple economics. The fake reviews tend toward the extreme–that is, they are always either one-star (exceptionally negative), or five-star (exceptionally positive) reviews. It’s in a business’s best interest to post negative reviews about its competitors and to boost its own review averages through a slew of positive reviews.

With the help of an army of third-party assistants, everyone’s doing it.

An advertisement for Silverman Slim’s, an online “review dealer.”

In the heady days of the mid-2000s internet, online “reputation management” or “search engine optimization (SEO)” firms were a big deal. In a process dubbed “astroturfing,” these firms paid armies of freelancers around the world to post positive reviews for their clients. And they did this with reckless abandon.

An anonymous former employee at Main Street Host, a self-titled “digital marketing agency,” told the Huffington Post: “five or six years ago you could have just sat there and posted everything from the same computer. Nothing mattered.”

But this was all headed for collapse. Though Yelp has measures in place to detect and remove fake reviews, the onslaught was too much for the company to handle.

Between 2012 and 2013, New York State Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, launched an investigation into the practices of these so-called “reputation management” firms. In order to lure fake reviewers, investigators participating in ”Operation Clean Turf” posed as the owners of a fictitious Brooklyn yogurt shop. They solicited proposals from a number of SEO firms, some of whom who offered to write fake reviews for the fake yogurt shop, and game Yelp’s review system to highlight the positive reviews.

Schneiderman’s report uncovered a much more sophisticated network of fake reviews than they anticipated. Some of the firms employed complex IP-spoofing techniques. Freelance writers–from as far afield as Russia and the Philippines–were encouraged to “write in the mindset of the consumer,” and constantly switch computers and locations to avoid detection by Yelp’s fraud-targeting system.

Worst of all, the freelancers were supposed to have been paid between $1 and $10 for each review they posted, while the SEO firms were to take a huge cut. And the companies wanted a lot for these meager payments: SEO company Webtools (which was caught in the sting operation along with the aforementioned Main Street Host), even gave its fake reviewers style tips, telling the ”content creators” not to use too many superlatives, and to make each review sound unique.

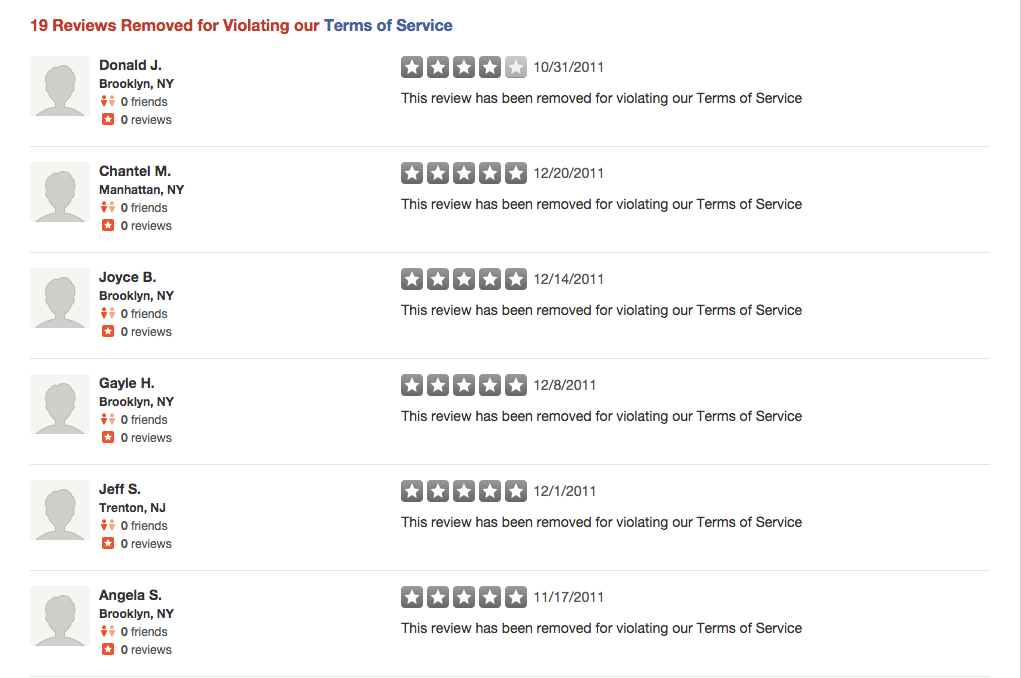

Following the sting operation, 19 companies offered to settle with the Attorney General’s office out of court, setting a precedent that fake reviews would not be tolerated in New York.

Fake reviews for a New York area orthodontist had been removed for violating Yelp’s terms of service. (Screenshot: Jeremy Berke)

But where there’s a will, there’s a way. If people were still out there writing fake reviews, I wanted to see how it worked for myself. Combing through the Attorney General’s report, I found a few sketchy “reputation management” firms that had not been caught in the sting operation.

I graciously offered them my skills to write fake reviews, and one company, the not-shady-at-all sounding Silverman Slim’s, actually got back to me. But getting paid to do the work was more difficult than I anticipated.

A representative explained via email that once Silverman Slim’s got “sales” for reviews in my area, they would kick me the link. Once I completed each review, I would get compensated through PayPal.

After expressing my enthusiasm for review assignments in both Brooklyn and Toronto—places I legitimately frequent—I didn’t hear back for a few days. I sent an email asking for an update. They responded by asking me to share their information with local businesses, negotiate a deal myself, and write the review. And after all that, they’d still take a cut of the profit.

It didn’t seem to add up.

Whatever the case with this particular firm, fake reviews are not going away anytime soon. In 2012, tech-market research firm Gartner estimated that, by 2014, up to 10-15 percent of social media reviews would be fake. It’s a brave new world, and we’re already living in it.

![Sometimes it's just nice to let the prima donna melt. (Photo: [TK]/Lisa Homa)](https://img.atlasobscura.com/0xPp8mKRHUWistTaVXImW4x-H_favi4tfBU2B4Byl5Y/rs:fill:600:400:1/g:ce/q:81/sm:1/scp:1/ar:1/aHR0cHM6Ly9hdGxh/cy1kZXYuczMuYW1h/em9uYXdzLmNvbS91/cGxvYWRzL2Fzc2V0/cy9kNWVmMTVmOWMz/MWRmYjc0NWFfVU1f/SWNlX0NyZWFtLmpw/Zw.jpg)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook