How Ireland Uses Shamrocks to Gain Access to the U.S. President

It all goes down during an annual St. Patrick’s Day ceremony at the White House.

It was quite the unlucky rollout. Ahead of St. Patrick’s Day, President Trump’s online shop debuted a green version of his signature “Make America Great Again” hat. To “capture the luck of the Irish” this March 17, the back of the $50, limited-edition cap featured a gold-embroidered, four-leaf clover. But the emblem of St. Patrick, and a broader symbol of Ireland, is an altogether different species: the three-leaf shamrock, which, legend has it, the celebrated saint used to teach the concept of the Holy Trinity in his fifth-century ministry. Many Irish, long accustomed to the confusion, quickly called out the sham on social media, and the hat soon after vanished from Trump’s website. Clover-gates aside, though, the shamrock is no stranger to politics this time of year, thanks to the annual “Shamrock Ceremony” at the White House.

On or around St. Patrick’s Day, the Irish taoiseach, or prime minister, presents the U.S. president with a crystal bowl brimming with live shamrocks as a symbol of the close ties between the two countries. After the leaders confer, a luncheon, and sometimes dinner, follows. The reception toasts the long legacy of the Irish in America and overflows with every manner of green attire and stilted lilts. Today, the Shamrock Ceremony can seem like an inevitable fixture of American-Irish affairs, but it began with a tiny sprig of diplomatic genius.

On March 17, 1952, President Harry Truman was viewing some baby seahorses at the Key West Aquarium. Back in Washington, Irish Ambassador John J. Hearne left the president a small box of shamrocks, traditionally pinned on a lapel or blouse to mark St. Patrick’s feast day. Nearly 70 years later, those humble tufts bloomed into the full-on cultural institution we take for granted today.

To many Americans and Irish alike, the symbolism of the Shamrock Ceremony verges on diddly-eye tokenism. Consider a few of the most groan-worthy Irish jokes presidents have told at the event over the years. Eisenhower once offered: “Wouldn’t it sound funny if I tried to say O’Eisenhower?” Gerald Ford started off an address: “All Americans know there is a bit of the green in the red, white, and blue.” When not threatening Democrats with shillelaghs, Reagan quipped of the holiday: “Leave it to the Irish to be carrying on a wake for 1,500 years.” George W. Bush jested: “Taoiseach, good morning—or should I say, top o’ the morning.” And last year, Obama attempted some Irish lingo while touting his heritage: “The Obamas of Leinster are nothing if not welcoming. We’ve got trad. We’ve got pints of black. It’s up to you to provide the craic.”

In spite of all of the pageantry, it’s “a deadly serious day” for the Irish government, says Dr. Michael Kennedy, Executive Editor of Documents on Irish Foreign Policy. “In officialdom, this is something absolutely unique to have 15-20 minutes with the most powerful person in the world. No other small country like Ireland has it.” He adds: “You can tell jokes about paddywhackery until the cows come home, but you’ve still got that access.”

Back in 1952, Hearne shrewdly recognized “the soft power of shamrock,” Kennedy says. Dubbed Ireland’s Thomas Jefferson for his work in drafting its 1937 constitution, Hearne was the first official Irish ambassador to the United States. Then, the young republic was eager to be seen as a modern state. But its relations with the U.S. had soured over its neutrality during World War II and refusal to join N.A.T.O. What’s more, Ireland detested the previous U.S. ambassador, Thomas Gray. Hearne’s box of shamrocks was a small but strategic effort to hit reset.

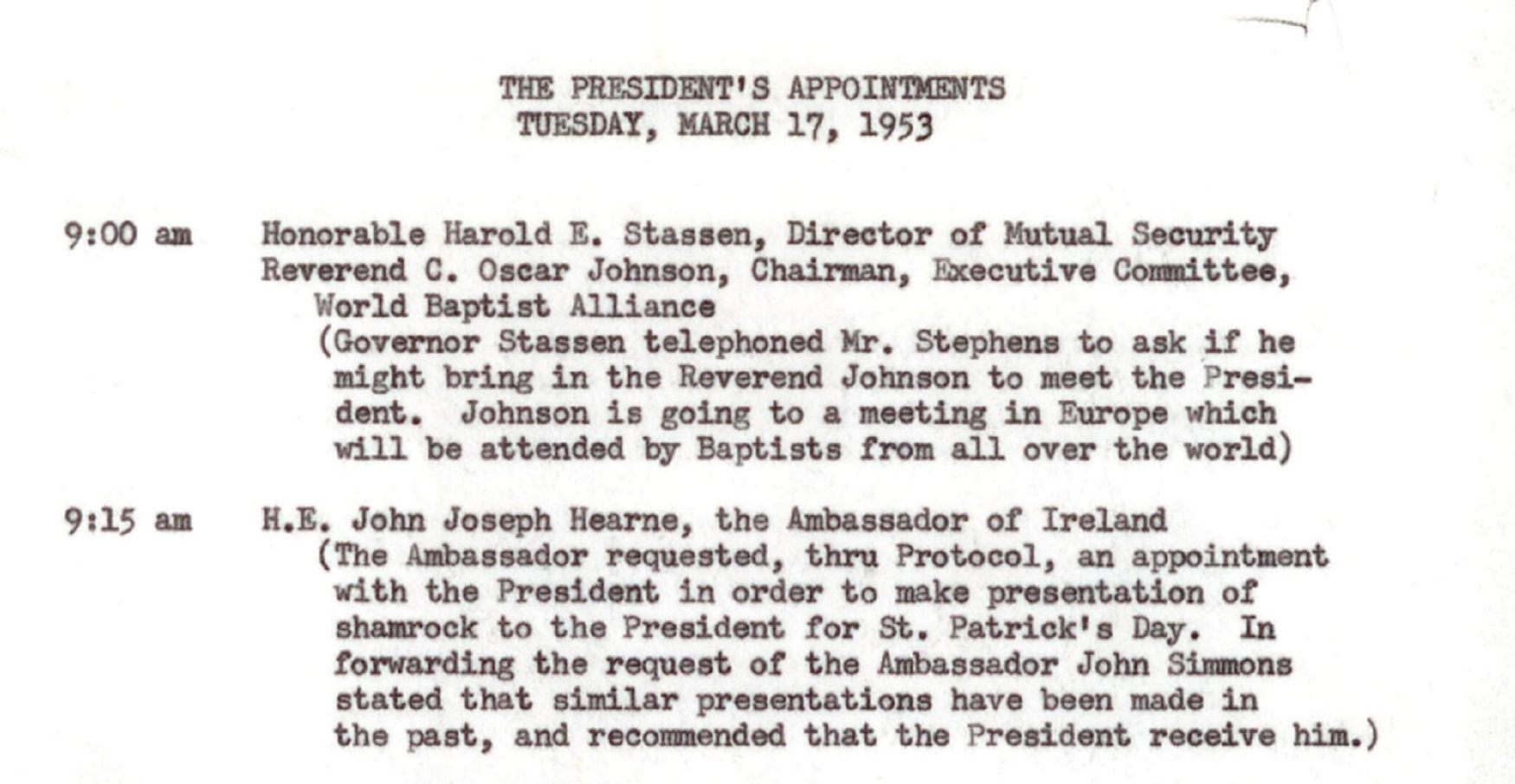

Hearne’s most brilliant move, though, may have come the following St. Patrick’s Day. As entered in Eisenhower’s presidential diary: “The Ambassador requested, thru Protocol, an appointment with the President in order to make presentation of shamrock to the President for St. Patrick’s Day … [Chief of Protocol] John Simmons stated that similar presentations have been made in the past, and recommended that the President receive him.”

Thanks to Hearne’s cunning follow-up, the tradition “greened” the White House over the next 11 administrations, almost without interruption. Eisenhower invited the first taoiseach in 1956. Under Kennedy, Ambassador Thomas Kiernan introduced the media and the now-traditional crystal for the U.S.’s first Irish Catholic president.

By the time of the Obama administration, which first dyed the White House fountain green, the ceremony had settled into its current fanfare, though it also remains a critical occasion to discuss political and financial issues between Ireland and the U.S. Now, Michael Kennedy says Ireland’s yearly face-to-face with the president gives it more diplomatic “wiggle room” at the U.N.

For such a high-profile event, the shamrock comes from Living Shamrock, “a single grower in Ballinskelligs, County Kerry,” says Horkan’s Garden Centre, which coordinates shamrock gift shipments around the world. Roots intact, it arrives in Washington primed for planting.

But the State Department’s 2007 “Report of Tangible Gifts” suggests the shamrock, valued at $5.00, was “handled pursuant to the United States Secret Service policy”—that is, destroyed for security purposes, or, as some Irish have joked, massacred. A comment by Ford in 1975 suggests, though, he may have taken his to Camp David, while Obama indicated his 2010 shamrocks made it into the White House garden.

“I cannot confirm nor deny the Ford and Obama stories,” Dr. Matthew Costello, Senior Historian at the White House Historical Association says by email, “but I would highly doubt that these shamrocks were saved and planted elsewhere.” Shamrocks, he explains, are a potentially invasive natural species that must be destroyed by law.

But Costello says one cluster of shamrock did find a final resting place. As The Washington Post reported on March 19, 1964: “Mrs. John F. Kennedy paid a St. Patrick’s Day visit to her husband’s grave in Arlington National Cemetery Tuesday and placed on it a cluster of shamrock which had been presented to her by Ireland’s Ambassador Thomas J. Kiernan.”

As for the bowls? For the past several administrations, the Department of the Taoiseach tenders designs from glass-crafters from around Ireland each January, says the State Protocol office. Based on quality, price, and workmanship, they commission a piece from the winner. The National Archives and Presidential Libraries now house dozens of these gifts, as a 1966 law prevents federal employees from keeping foreign gifts exceeding, currently, $390. (Obama’s 2015 bowl, as catalogued by the State Department’s Protocol Gift Unit, is estimated to be worth over $10,000.)

“Most presidents kept the bowls in the [White House] during their time there,” says Costello, as is permitted before they head to the archives. Reagan notably filled his with his beloved jellybeans—green ones. And “Clinton mentioned the Irish crystal was on display on the Second Floor of the White House in the Residence,” according to Costello. And Hearne’s fateful box? “I’m afraid we just don’t know exactly where it is,” Costello says.

The public won’t see the 2017 bowl, handmade by Criostal na Rinne, until its ceremonial debut. But a lot of Éire eyes won’t be looking out for crystal (or four-leaf clovers): They’ll be watching how Taoiseach Enda Kenny interacts with President Trump. Many Irish hoped the taoiseach would leverage the soft power of their shamrocks in a symbolic break from the longstanding tradition this St. Patrick’s Day. But Kenny will be coming, bowl of shamrocks and all: Hearne’s simple sprigs, plucked so many decades ago, have sunk some deep political roots.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook