Mapping Ireland’s Mysterious Carvings of Old Women Exposing Their Genitals

Sheela-na-gigs can be found all over the country, but it’s only recently that academics have been brave enough to study them.

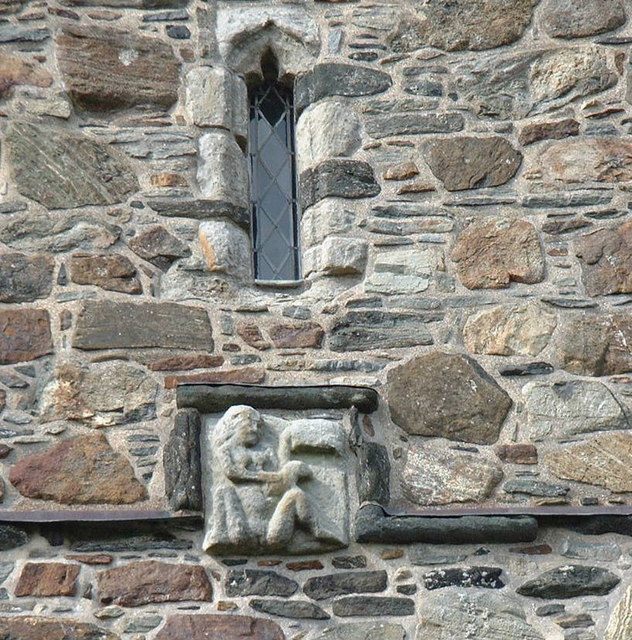

Sometime in the 1940s, workers repairing a culvert in Limerick, Ireland, pried a stone out of the ground, flipped it over, and found a surprise waiting for them on the other side. Carved into the rock was a headless figure, with drooping breasts and a round navel. One of her hands had crumbled away, but the other was doing something unmistakable: pulling a thigh aside to better expose her vagina, which had been chiseled deep into the stone.

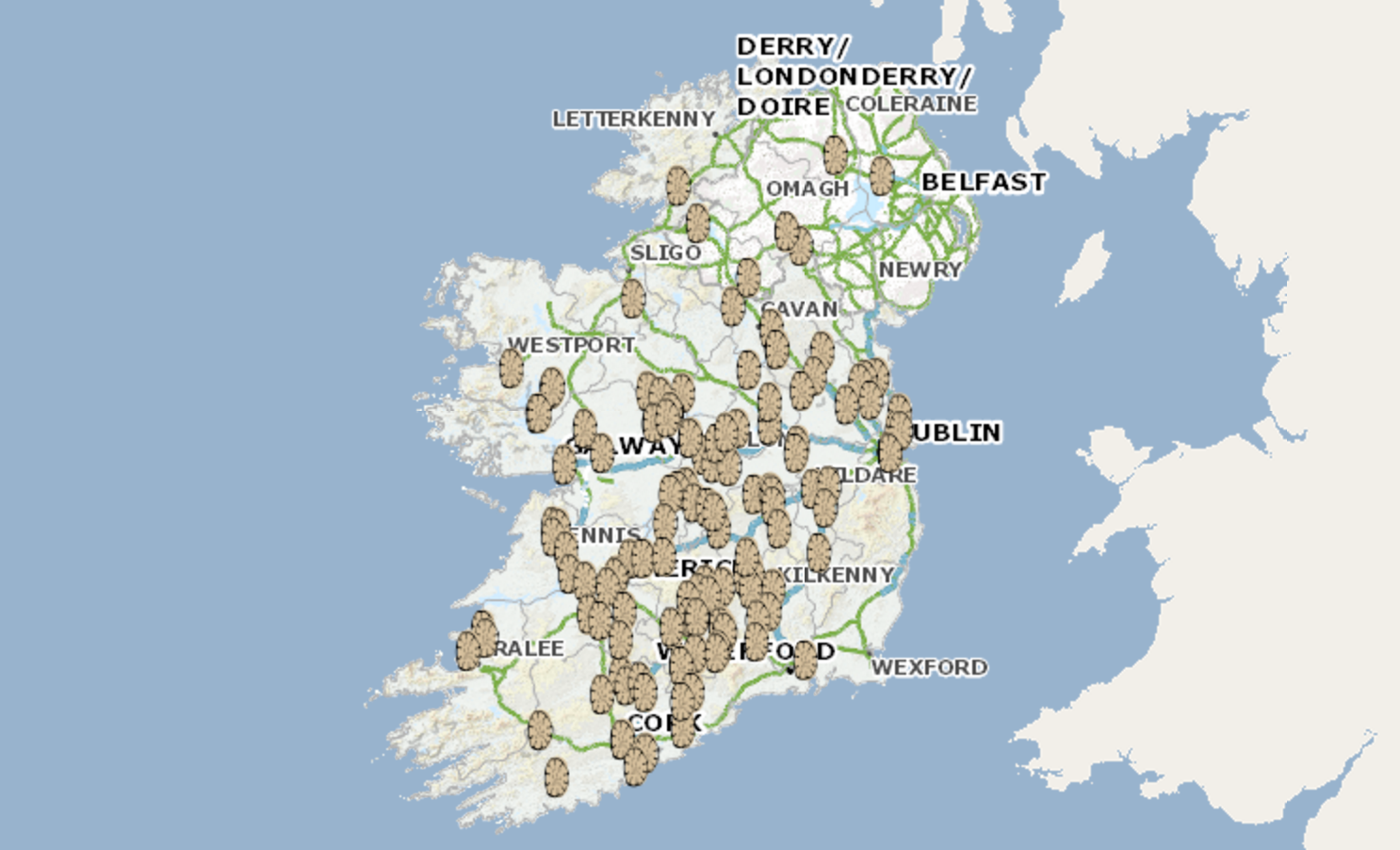

The carving is one of Ireland’s many Sheela-na-gigs: mysterious depictions of old women displaying their genitals. Once considered too vulgar for either scholarship or display, interested parties can now explore all of the known Sheela-na-gigs in Ireland thanks to a brand new interactive map from the country’s Heritage Council. “We realized that no dedicated map of these wonderful sculptures existed,” writes Patrick Reid, a GIS consultant for the Council, in an email. “So we decided to fill this gap.” (To use the map, follow the link above, click “Layer List,” then “Archeology,” then “Sheela-na-gig.”)

Today, Sheela-na-gigs are considered undisputed archeological treasures. Most date back to medieval times, when they were a standard element of decor for churches, castles, and other important rural buildings. Their craftsmanship and placement, combined with the unusual choice of subject, make them “very evocative symbols of the feminine in old Irish culture,” says Beatrice Kelly, the head of the Heritage Council, in a statement.

It has taken the carvings a while to gain this academic reputation, though. The first modern discovery of a Sheela-na-gig, in the wall of a Tipperary church in 1840, inspired an angry letter from its finder, Thomas O’Conor, who was very confused that this “ill executed piece of sculpture,” which promoted the “grossest idea of immorality and licentiousness,” should be anywhere near a church.

O’Conor’s reaction would set the scholarly tone for decades to come. Until recently, experts largely wrote Sheela-na-gigs off as unworthy of serious consideration. Museums kept them in basements, and clergymen removed and sometimes even destroyed them. (The carving discovered by workers in 1940 was probably made for a nearby castle, before more prudish inhabitants hid it face-down in the culvert wall.) “Only in the less puritanical atmosphere of the past few decades have academics and artists turned their interest to Sheela-na-gigs,” as the historian Barbara Freitag explains in her book on the subject.

As a result, many mysteries remain. While some experts maintain that the carvings are meant to warn against lust, others, including Freitag, posit that they instead represent fertility and rebirth. Even the name, which was was also first recorded in the 1840s, is shrouded in confusion, as it does not have an obvious translation—some interpret it to mean “old woman of the breasts,” while others go with “supernatural river goddess,” or “castle hag.”

With so much still to be learned, Reid and his team hope that their map might help scholars make up for lost time. To create it, they first scraped Sheela-na-gig locations from Ireland’s National Monument Service, which keeps an up-to-date list. They then supplemented as many entries as possible with historical information, descriptions, and images, sourced from museums, experts, and what Reid calls “inspiring amateur Sheela-na-gig enthusiasts.”

In this way, they’ve provided a sort of national, virtual exhibition: click on a particular part of Ireland, and you’ll meet that area’s resident Sheela. Over the years, many have been relocated or repurposed, and reading about each gives a sense of the changing meanings afforded to them. One, carved into a window spandrel, was only discovered in 2002, because it blends in so well with the surrounding decorations. Another, in Sligo County, has been painted pink. A third—relatively small, and doing an impressive full split—formerly watched over Scregg Castle, and is now “built into the southern pier of a nearby outhouse.”

The map stretches from Ballynacarriga, on the country’s southern edge (which has a big-headed Sheela, with “huge droopy ears and asymmetrical eyes”), all the way north to Maghera, in Derry County (where one is carved into a church tower, about 20 feet up). In total it currently offers 110 Sheelas, enough to satisfy most anyone’s curiosity.

The mystery, though, spreads out beyond Northern Ireland—another map, made by a separate group, maps Sheelas and “other exhibitionist figures” in Britain, Scotland, and Wales, and similar carvings have been found in Norway, Spain, and elsewhere. Although the Heritage Map project focuses specifically on Irish carvings, “we do hope that our map will aid and stimulate Sheela research at a European level,” says Reid.

Their main goal, though, is to get everyone talking: “The aim… is to help re-introduce them into both academic and popular cultural debate,” writes Reid. In this particular mission, the Sheelas’ striking choice of pose may finally help them.

Map Monday highlights interesting and unusual cartographic pursuits from around the world and through time. Read more Map Monday posts.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook