Solving the Nutritional Mystery of Historical Food at Sea

Was the food really as bad as sailors claimed? There’s only one way to find out.

Mealtime on board the USS Olympia, 1899. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-128415)

It’s easy to take salt for granted. Cheap and plentiful, it’s not the sort of the thing you expect to find mixed with the dregs of human existence, especially when you’re seasoning a nice cut of meat. But salt in earlier centuries was not the same as the salt we have today. According to one account of French bay salt in 1746, it was “always mixed with dirt and nastiness which makes up a full seventh part.”

“The filth arises from putrefied human bodies, dead fish and the carcasses of animals,” the writer continued, “and from most immense quantities of different kinds of rotten weeds together with innumerable other unwholesome mixtures brought into the salines by the tide.”

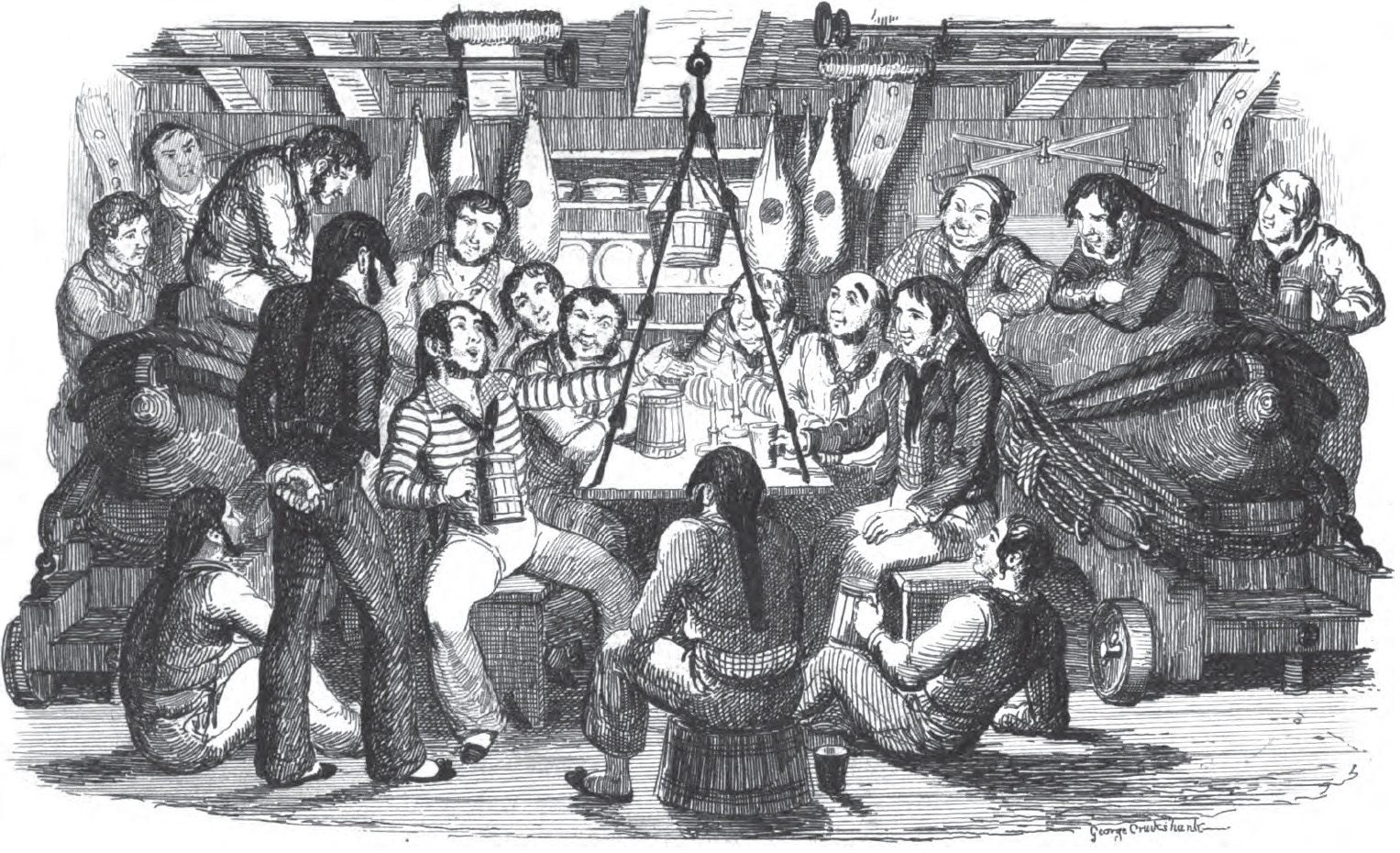

An illustration titled Saturday Night At Sea from a book of songs, published in London in 1841. (Photo: Thomas Dibdin/Public Domain)

Now imagine that mixed into a boil and poured atop chunks of freshly butchered beef. And then imagine that being one of your only sources of food for the next three months on a ship at sea. That’s about as luxurious as it got for sailors in the 17th century, in a time before canning or refrigeration. Things often spoiled, and nutritional value suffered, often a direct result of how food and drink were preserved. Things that could keep became staples, such as ship biscuit, beer and wine, a balanced breakfast be damned.

But researchers want to go beyond diaries and journals to find out how ship diets worked. They want to make the food itself. On a boat.

“No one really knows if the food they were eating was really that bad, or if [diaries] were written by sailors who just really hated the food, or whose ship happened to get a bad batch of rations,” Grace Tsai, a PhD student specializing in nautical archaeology at Texas A&M University, tells me over the phone.

Past studies, according to Tsai, have tried to derive nutritional information based on historical documents, rather than in the lab, with little success. Which is why, since 2014, Tsai and her team of fellow PhD students have been preparing to make salted beef, ship biscuit, beer and wine as closely as possible to how they were made in the 17th century—right down to the type of ingredients and storage containers used. Next August, those foods will go on a simulated voyage in a real ship, and be sampled every ten days for nutritional and microbial analysis over a period of three months.

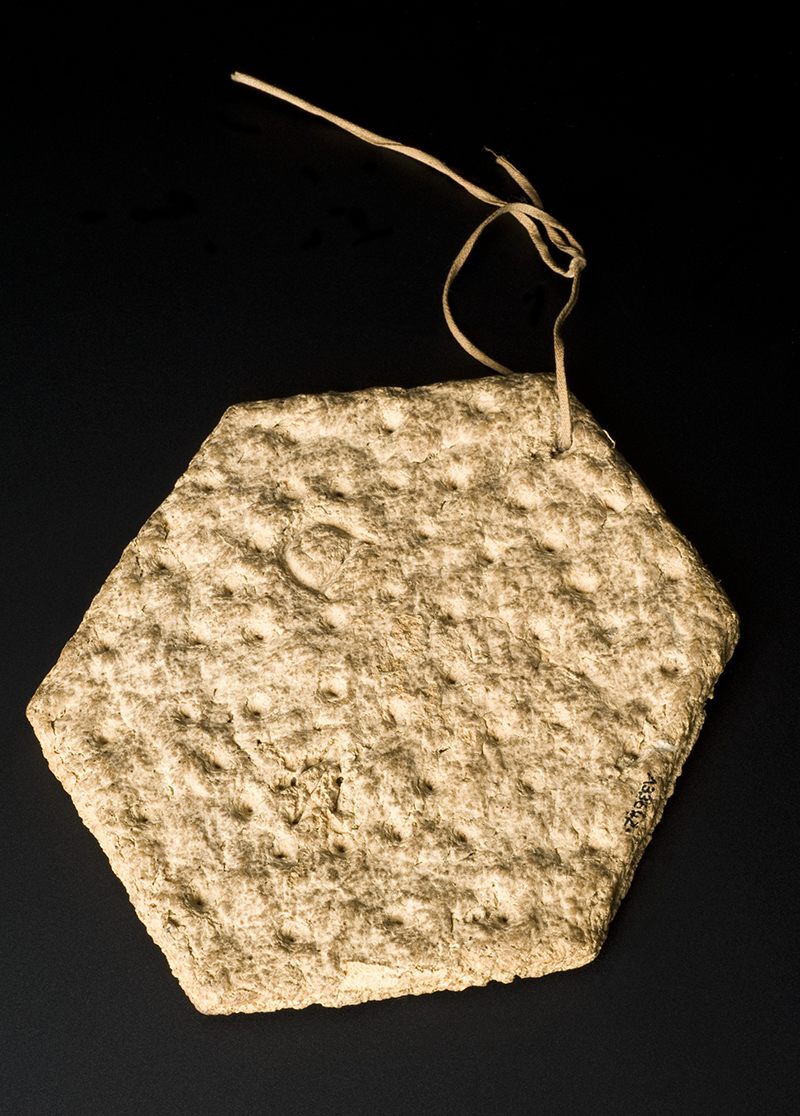

A staple to a sailor’s diet - a ship’s biscuit, from 1875. (Photo: Wellcome Images, London/CC BY 4.0)

The hope is to paint the most accurate picture yet of shipboard food quality and sailor health at sea, said Tsai, the project’s director, which is jointly funded by the university and the Institute of Nautical Archaeology. But making those rations accurately will be no small feat.

There’s a reason past experiments have tried, unsuccessfully, to extrapolate nutritional content from modern day foods and ingredients instead. Making historical food in the present day is hard. The team has given itself over a year to test their methods and gather supplies.

To start, Tsai consulted manuals and cookbooks dating from the 15th to 17th centuries, which detailed various methods and guidelines for obtaining and preparing ingredients, as well as documentation kept by ships and ports. Unsurprisingly, some ingredients have been easier to track down than others. Ship biscuit, for example, was essentially just a cracker—“unrefined wheat, flour, mixed with water, sometimes a little bit of salt, sometimes a little bit of yeast, then it was baked twice,” Tsai explains—and so hasn’t posed much of a problem. But on the other hand, finding the right type of salt for the salted beef has been difficult. Tsai says they may import it from Europe, sans the human and animal remains, of course.

The beer is a little bit easier. Christopher Dostal, the project’s historical beer consultant, says historical recipes brewed today taste “surprisingly not as different as you might expect” because the ingredients and processes are in many ways the same. Nevertheless, while they know the water profile of their intended English Ale, which is specific to the location of where it was brewed, and the hops and grain that were likely used, the specific strain of yeast is impossible to know. “People don’t really know what was used in the past,” Tsai says.

Portugese galleons from the 16th century. (Photo: British Library/Public Domain)

And then there’s the challenge of actually making the food. The team’s cattle specialist Meg Hagseth believes they’ve tracked down the specific breed of cattle, a Devon, which still exists today. But butchering the meat is another matter. In those days, if you cut too large, the salt couldn’t penetrate deep enough into the meat, and the meat would rot from the inside out. Too small, and you exposed more of the meat to oxygen, which caused it to degrade faster (and also, increased the risk of contamination, when you’re handling more meat directly).

“It needs to be pretty precise, otherwise it probably won’t hold up for very long,” Tsai says.

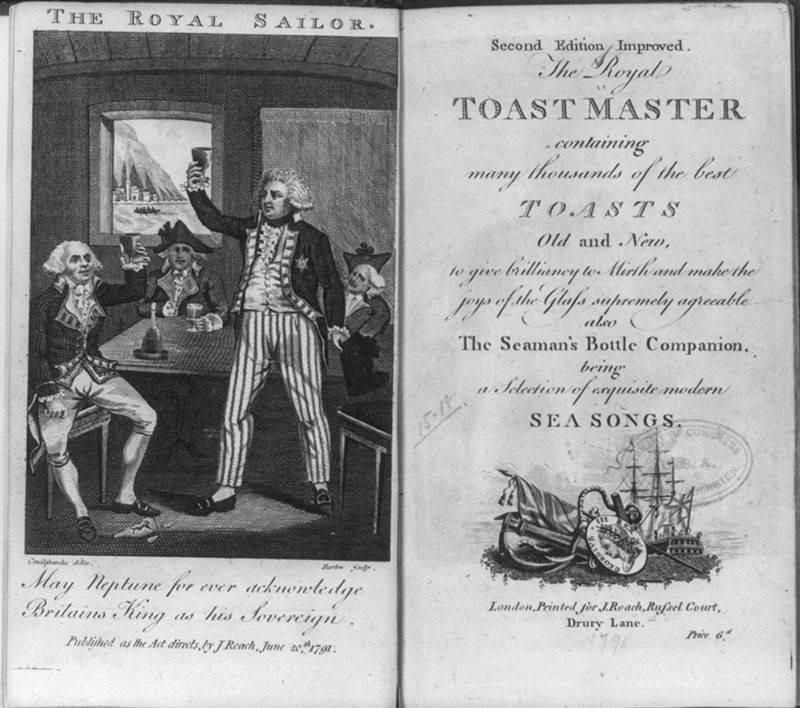

Four Naval officers raising a glass in the title page to The Royal Toastmaster, a 1791 book “to give brilliancy to Mirth and make the joys of the glass supremely enjoyable.” (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-71693)

As far as storage and transport goes, the project is being modeled on an English galleon, the Warwick, that sunk off the coast of Bermuda in 1619. The ship spent three months at sea, which is how long Tsai hopes her project will run. The materials will be stored in casks of the same size and wood as the originals, based on items recovered from the ship that Grace examined last spring. The ship biscuit was stored in canvas bags.

Of course, there are only so many variables within the team’s control. The containers will be stored, not on a wooden ship like the Warwick—hard to find in the best of conditions, but especially so in Texas—but a 19th century tall-ship, the Elissa, docked at a museum in Galveston. The Elissa is made from iron, and won’t be exposed to the same changes in environment that it would at sea (not to mention, it’s docked), which they hope will be close enough. Samples will be gathered and tests will be performed every ten days—which, in the case of the salted beef, will actually require opening the barrel, and re-sealing it each time—in addition to measurements the team can “see, feel, touch, but not taste,” says Tsai.

The Elissa, in port in Galveston, Texas. (Photo: Bill Staney/CC BY ND 2.0)

But when I talk to Dostal, there’s a slight difference of opinion.

“Of course we’re going to drink the beer!” he tells me with a laugh. “I’m personally not going to eat any salted beef that’s been ageing for a while, but beer’s beer.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook