Eating Spaghetti by the Fistful Was Once a Neapolitan Street Spectacle

Tourists flocked to see the “macaroni eaters” cram noodles into their mouths.

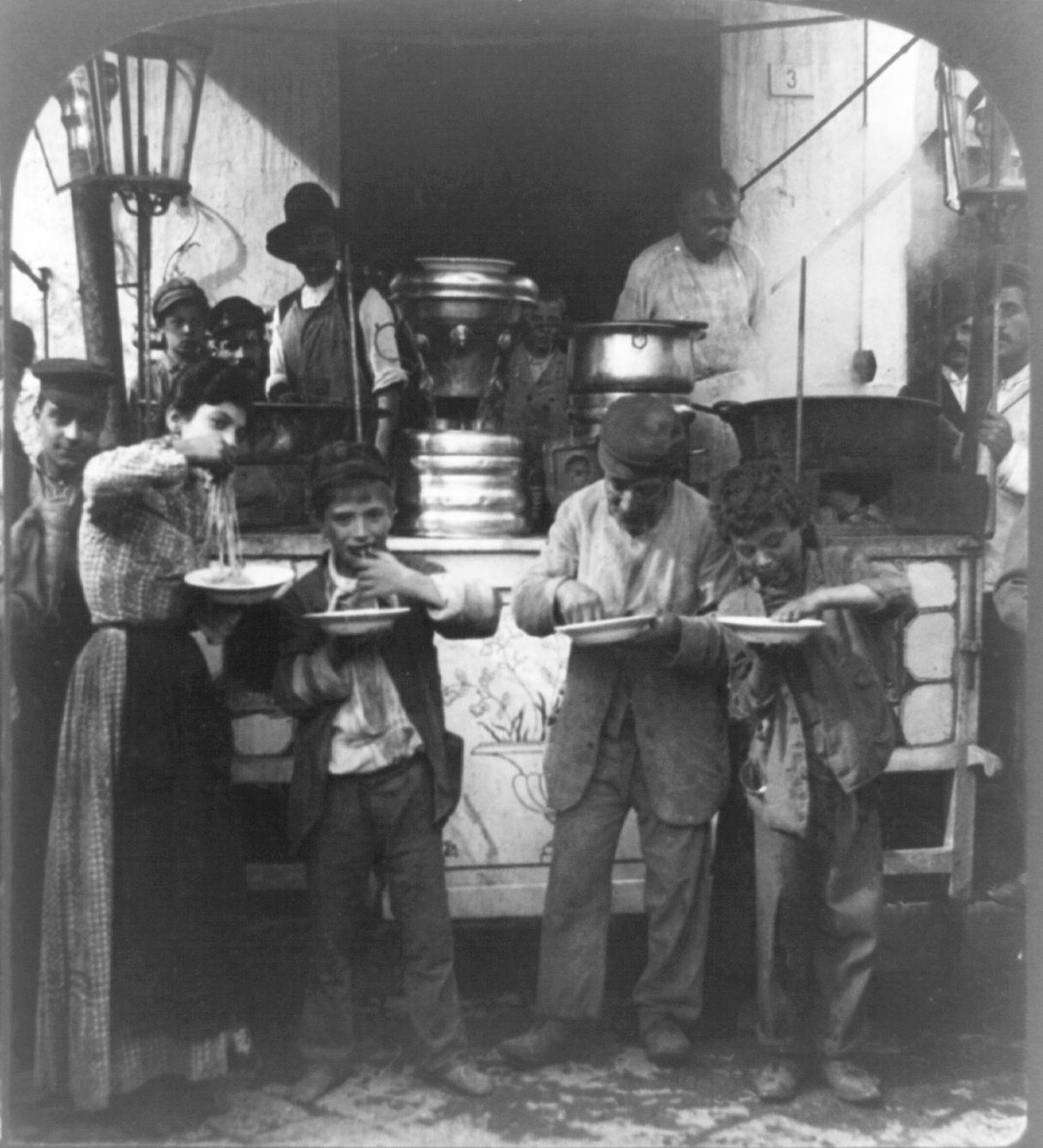

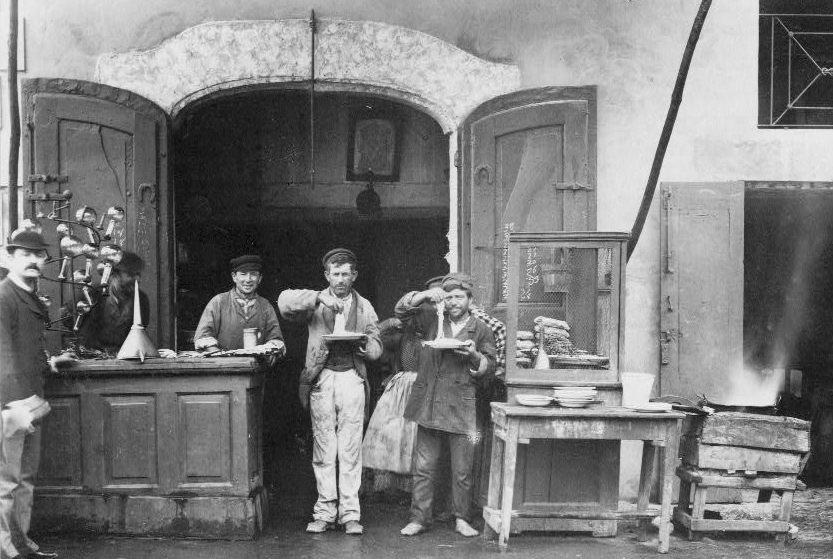

A hungry visitor strolling through the narrow streets of 19th-century Naples would have encountered a wealth of food options—some more tempting than others. Vendors hawked meats and cakes, women cooked up soups and omelets, and goats patiently awaited milking. Among those vying for attention would have been the pasta-sellers tending to cauldrons brimming with long strands of spaghetti writhing in boiling water. The spaghetti would have been fished out of its scalding bath and handed over to hungry men and women who then would have deftly lowered fistful of the noodles into their mouths in one gulp. These were the macaroni-eaters of Naples.

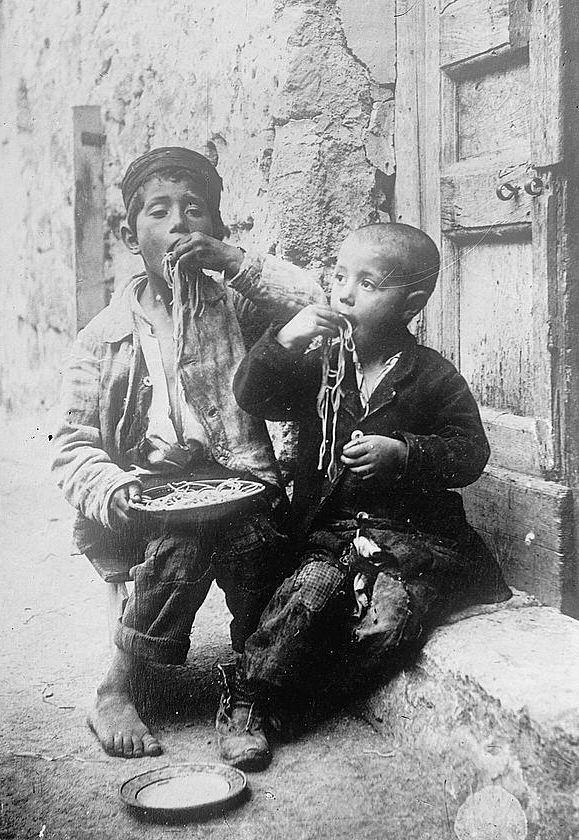

From the 17th to 19th centuries, macaroni, which was the term used for all forms of pasta, was a street food. And, like any proper street food, macaroni was eaten not with a fork, but with one’s bare hands.

Watching this custom in action was one of Naples’ major tourist attractions. The macaroni-eaters were written up in guidebooks, illustrated in paintings, and later captured in prints and on film for postcards. Some macaroni-sellers would even provide demonstrations to tourists willing to pay for a plate. Eating a handful of macaroni in a single bite was something of a sport, or at least a gastronomical challenge. In a book published in 1832, Andrea de Jorio, the Neapolitan clergyman and ethnographer, explained that to eat macaroni “the Neapolitan way” requires that the pasta be “swallowed down in a single, uninterrupted mouthful.” De Jorio further explains that the macaroni must be poured into one’s mouth “with both hands in such a way that there is no interval between successive mouthfuls, except what is necessary to allow the macaroni to reach the oesophagus.” Naturally, visitors found this endlessly entertaining.

Many tourists took it upon themselves to organize such spectacles. Simply tossing a coin or two to the lazzaroni, the street beggars, would elicit a mad dash to consume the macaroni in their characteristic way, much to the amusement of their onlooking benefactors. John Lawson Stoddard, an American visitor to Naples, wrote about one night when, while driving through a market, he stopped to buy 20 platefuls of macaroni just to watch people eat them. “The instant that one wretched man received a plate a dozen others jumped for it; [they] grabbed handfuls of the steaming mass, and thrust the almost scalding mixture down their throats,” he wrote. “I had expected to be amused, but this mad eagerness for common food denoted actual hunger.” Macaroni, as Stoddard discovered, was not just a Neapolitan idiosyncrasy, but an important form of sustenance for the poor. But it was not always so.

Pasta was first brought to Sicily by Arab merchants around the 12th century. It eventually made its way to Naples about 300 years later. The curious rope-like dough must have presented a challenge to early adopters. But by the mid-14th century, Italians had taken to eating macaroni with a fork. For centuries, pasta was only eaten by the wealthy on special occasions and by the peasantry as a rare indulgence. All that changed in the 17th century when macaroni-eating took to the streets.

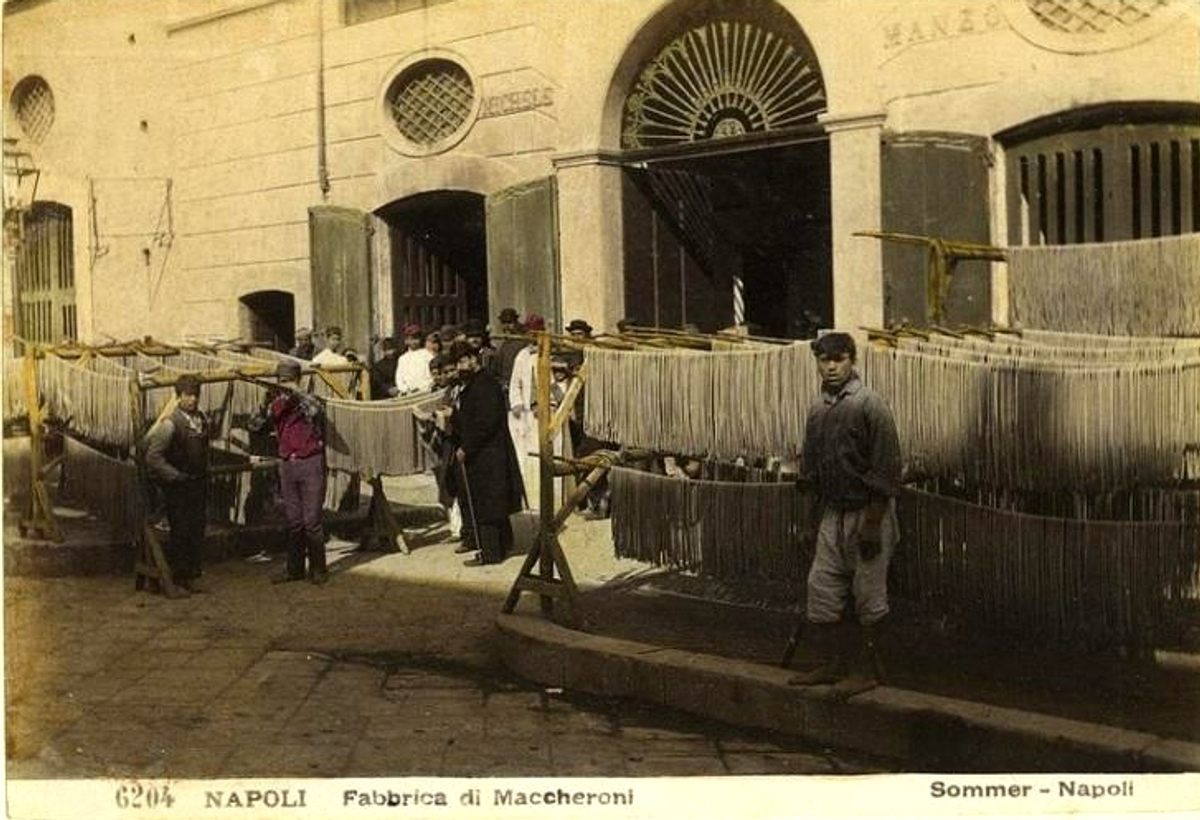

During the 17th century, the price of meat and vegetables rose and the price of bread and pasta dropped. At the same time, greater accessibility to kneading troughs and new mechanical presses enabled pasta to be produced at a lower cost than ever before. Naples, with its quality ingredients and sea air perfect for drying, became a center of pasta-making and pasta-eating. The Neapolitan working poor, who had long subsisted on a diet of mostly cabbage and meat, now relied heavily on pasta, which filled up hungry bellies and provided a wealth of calories. Neapolitans became known as “macaroni-eaters,” an epithet that had been reserved for Sicilians up until that time.

When Goethe visited Naples in 1787, he noted that ready-to-eat macaroni “can be bought everywhere and in all the shops for very little money.” These shops, which had more than quadrupled over the course of the 18th century, were mostly stalls on the streets and in the markets. The fresh pasta, made of durum wheat, was laid out near the stalls on cane racks or large cloths to dry in the bright southern sun and fresh coastal air. Macaroni-cooking was a simple affair: The pasta was boiled over a charcoal fire in a large pot of water. Occasionally the water was flavored with pork grease and a bit of salt. Other than that, grated hard cheese was the sole seasoning until tomato sauce was added in the 19th century.

While most Neapolitan pasta had a reputation for being some of the best in Italy, the stuff sold to the poor on the streets did not. A large part of the macaroni-eating population could only afford lower-quality macaroni which contained dirt and, unsurprisingly, had an acidic tang. The conditions in the macaroni shops were less than sanitary. Stoddard described “filthy men” making great sheets of dough which they then hung out to dry “amidst the dust, rags, and wretchedness of Neapolitan streets.” Stoddard did not divulge whether or not he tried the macaroni himself, but he did mention that a friend of his “was almost ill from merely recollecting that he had eaten macaroni here the night before, and nothing would induce him after that to touch the dish.”

In the 20th century, Naples’ dominance in pasta production steadily waned. In an effort to make Italy more self-sufficient, Mussolini moved the growing of durum from the south to the center and north of the country. Soon, northern factories were making pasta and using electric drying tunnels instead of the once coveted Neapolitan sun and breeze. Pasta-eating eventually moved off the streets and back indoors, where hands that had once scooped up fistfuls of macaroni now held forkfuls instead.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook