Rediscovering the Civil War Heroics of a Tiny Massachusetts Armory

By pioneering mass production techniques, it played a unique role in U.S. history in more ways than one.

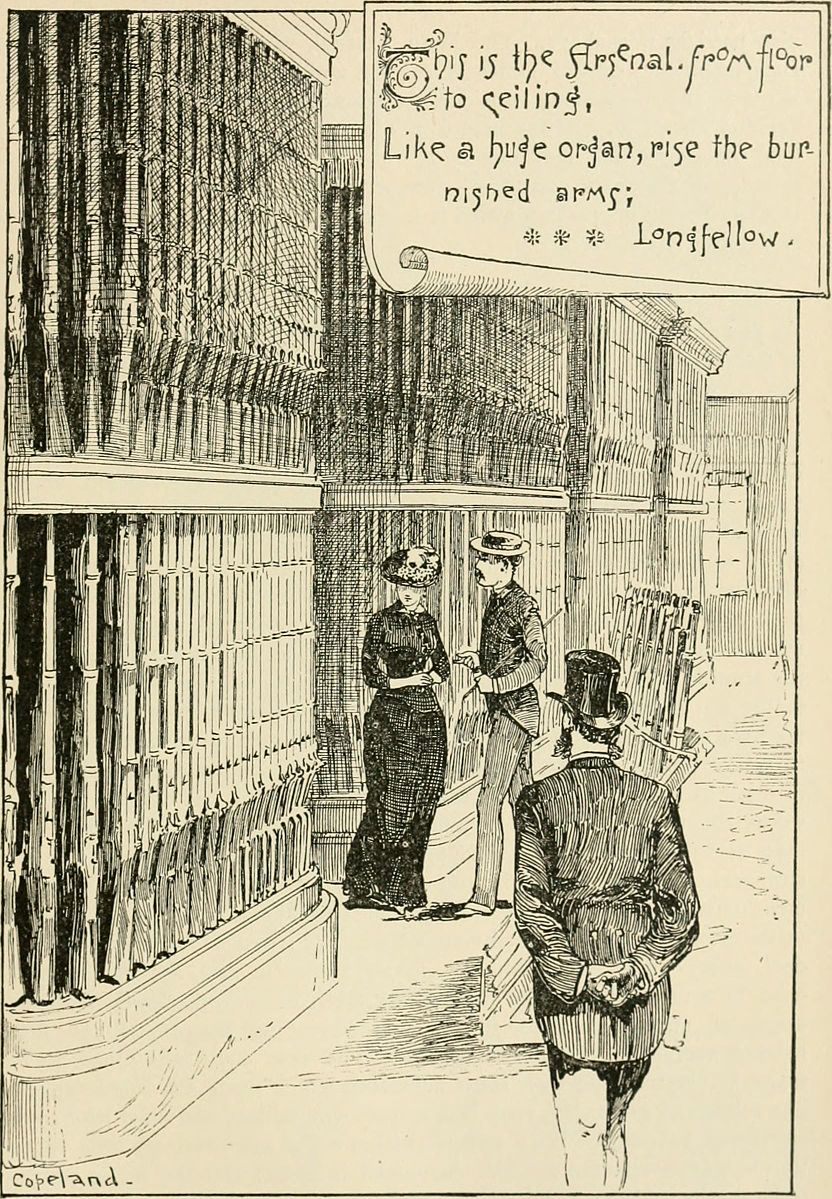

In 1843, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and his new wife, Fanny, made an unusual honeymoon stop: in between jaunts to the Berkshires and the Catskills, they swung by the Springfield Armory, a small, federally owned weapons manufactory in Western Massachusetts. As they walked through the factory, gaping at gun stands that held tens of thousands of identical rifles, the Longfellows felt a sense of dread. “I urged H to write a peace poem,” Fanny later remembered.

He did just that—“The Arsenal at Springfield” was published in 1845. In it, Longfellow describes both the “huge organ” of guns that greeted him at the factory, and his hope that, soon, “there were no need of arsenals or forts.”

It was not to be. Twenty years after the Longfellows’ visit, civil war erupted, and the Springfield Armory kicked into high gear, churning out hundreds of thousands of rifles and arming a full third of Union troops. By perfecting interchangeability and pumping up their production line, the Springfield Armory went from practically empty to a well-oiled rifle-making machine in just a few short years.

“The Springfield Armory rarely appears in Civil War histories except perhaps as an unexplained statistical wonder,” writes Michael Raber in a new paper in Arms & Armour. But, he argues, it was also more than that—“Springfield’s response to wartime demands… may have been among the first examples of American mass production,” he writes.

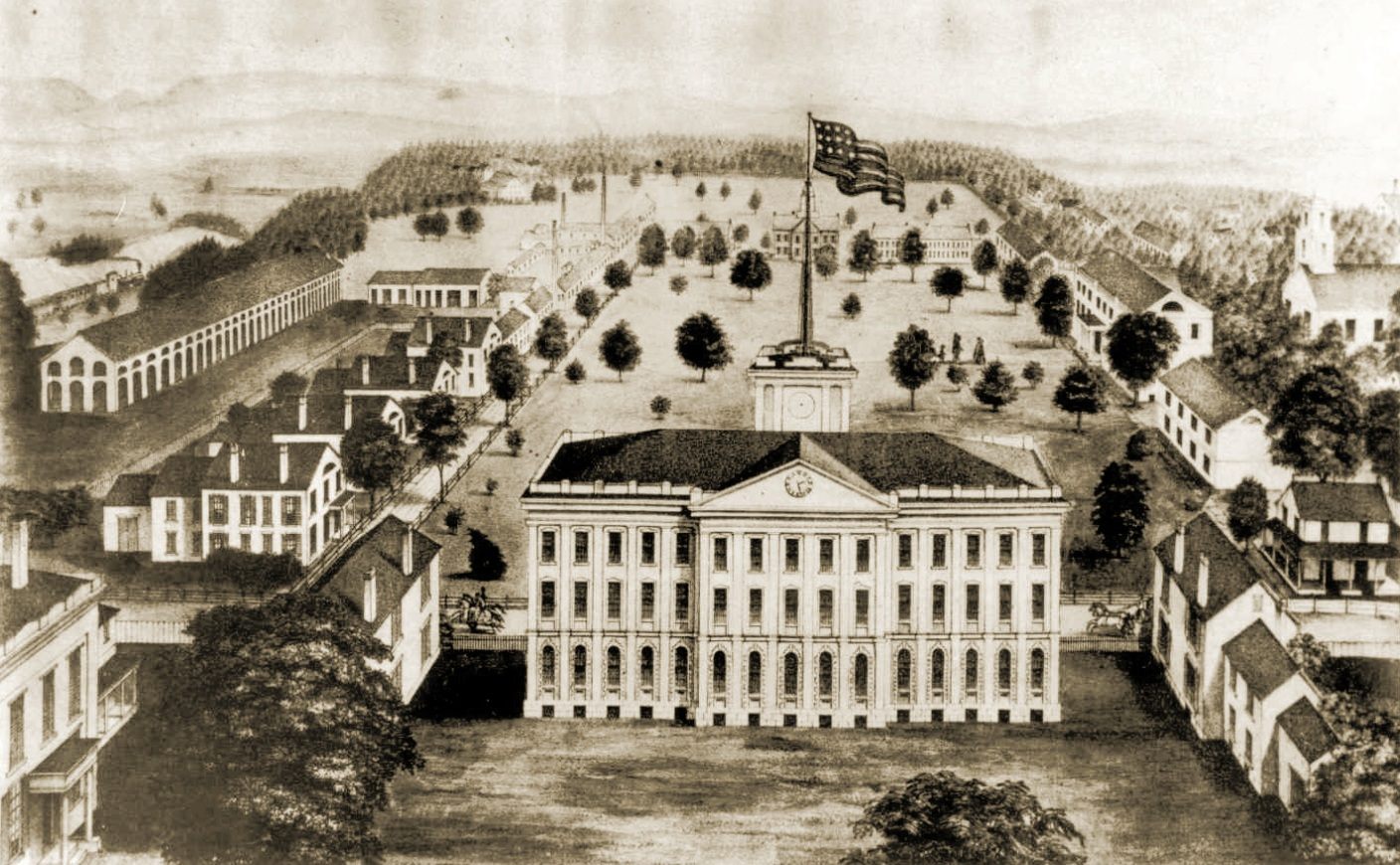

The Springfield Armory grew up with the country, playing a shifting but vital role in a large number of U.S. military conflicts. Throughout the 17th century, local militia would drill on the bluff where it was eventually built, which overlooks the Connecticut River. At the outset of the Revolutionary War, when George Washington was seeking a spot for an arsenal, he chose that same bluff, building barracks and storehouses there, as well as stockpiles of weapons.

During Shays’ Rebellion, rebels targeted the Springfield Armory, hoping to use it to arm themselves further and overthrow the Government of Massachusetts, but the state militia kept them at bay with grapeshot; a few years afterwards, in 1794, large-scale manufacturing began. The Armory was also involved in later conflicts: just before World War II, a Springfield-based armsmaker designed the M1 semiautomatic rifle, which General George S. Patton Jr. called “the greatest battle implement ever devised.”

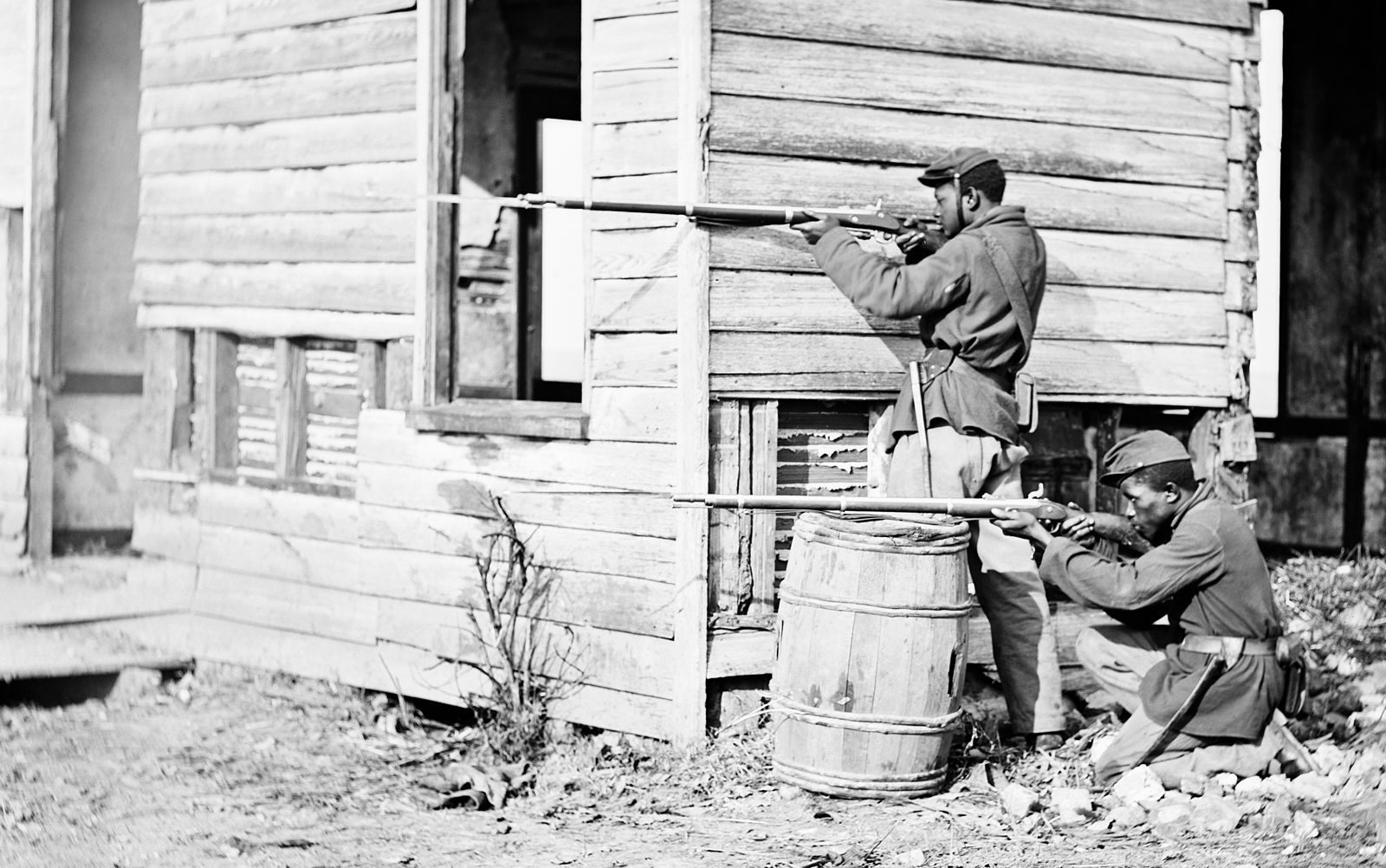

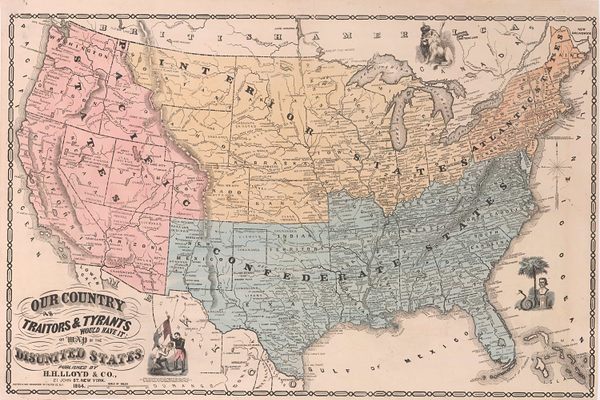

But it was during the Civil War that the Armory really shone, Raber argues. As he explains, the Union Army started the war at something of a disadvantage—in the years before war broke out, they had sent large quantities of arms and equipment down South, under orders from soon-to-be Confederate generals Jefferson Davis and John Buchanan Floyd.

To make matters worse, just a few days into the Civil War, the other Union armory, at Harpers Ferry, was destroyed in battle. The Union Army’s Ordnance Department quickly emptied the Springfield storehouses to arm the first waves of troops. It was up to the Springfield Armory to refill itself.

Within a few months, they proved themselves up to the task. “So many rifles and bayonets are now being turned out of the Springfield Armory, that if our armies lost theirs in every battle they could be replaced in a very short time,” wrote a Harpers Weekly reporter in a September 1861 profile of the institution. Under the joint direction of Ordnance Captain A.B. Dyer and Assistant Superintendent George Dwight, the Armory continued to grow over the next two years, soon outstripping private contractors and foreign importers to become the largest supplier of shoulder arms in the United States. “The works are daily turning out enough to arm an entire regiment,” marveled the technical writer George B. Prescott in 1863.

As Raber explains, Springfield’s dominance was partly the result of their devotion to a principle called “interchangeability.” Building weapons with completely identical, swappable parts had been a goal of the American military since soon after the Revoultionary War—in 1785, Thomas Jefferson wrote to John Jay about a French inventor who had proposed “making every part of [a musket] so exactly alike that what belongs to any one may be used for every other musket in the magazine.” By 1849, the Springfield Armory was producing standard-issue army rifles made of completely interchangeable parts.

When the war hit, they put this knowledge to good use. Dwight quickly expanded the facilities, added steam power, and—since the rifles were being shipped out as fast as they were made—dragged more machinery into what had been stockpiling rooms. Captain Dyer also outlawed smoking in the shops, to reduce the risk of fire.

In the month before the war began, the average Armory worker produced 43 rifles, writes Raber. By the beginning of 1862, that number had risen to 84 rifles per month. By May of 1863, the factory average topped out at 120 rifles per worker, nearly a 300 percent increase in productivity. Dyer kept wages high to attract new workers, both to ramp up production further and to replace those who had been drafted. Eventually, the Armory employed nearly 3,000 people working ten-hour shifts, seven days a week.

Raber argues that another part of the Armory’s success came from a certain resistance to progress. Although the Armory also made ammunition, replacement parts for other weapons, and bits for military horses, they produced just one particular type of rifle throughout the war—the Model 1861—making only the occasional change for safety reasons.

Even when soldiers, pundits, and President Lincoln himself made the case for other weaponry types, the Ordnance Captain kept the Armory churning out Model 1861s. “Making essentially the same [rifle] throughout the war avoided… extensive re-tooling and production delays,” writes Raber.

By the time General Kirby Smith surrendered the Confederate Department of the Trans-Mississippi in June of 1865, the Springfield Armory had built nearly 800,000 rifles. In Raber’s mind, this was not just an achievement in itself, but a potential important first, and a harbinger of things to come. “The initial achievement of mass production has often been credited to self-publicized 20th-century makers of automobiles,” such as Henry Ford, he writes. “[But] it is hard to see the wartime Armory as engaged in anything other than mass production.” Perhaps it was not the Model T that first exemplified what we now see as all-American principles of ingenuity and replicability, but the Springfield Armory and the Model 1861.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook