The Alarming Aesthetics of Jazz Age Perm Machines

Mix dangling wires and asbestos to achieve the perfect flapper wave.

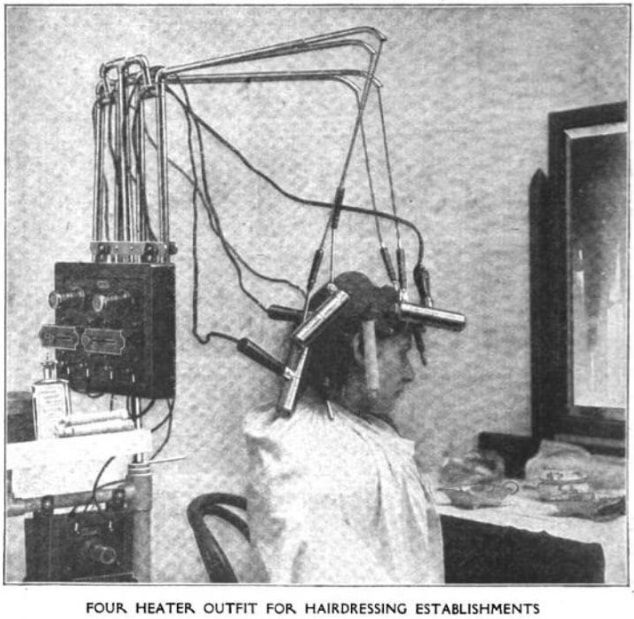

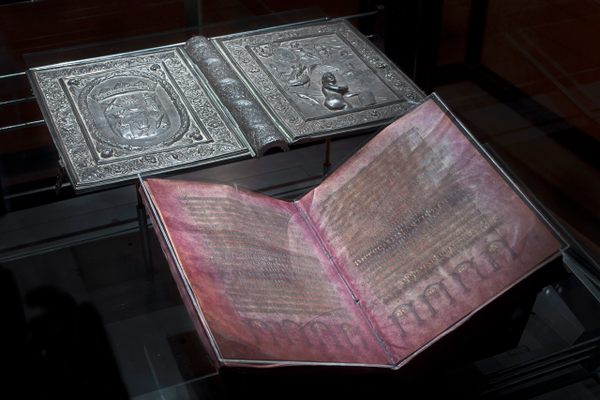

An Icall permanent wave machine from 1923 (left) and hair wound and ready for tubular heaters in 1934 (right). (Photos: Louis Calvete/CC BY-SA 3.0)

The perm may be the unofficial hairstyle of the ’80s, but the perming process originated many decades earlier—and involved machines that resembled medieval torture devices rather than sleek salon appliances.

“Science has pronounced straight hair to be freakish,” declared a haircare ad in a 1922 issue of Harper’s Bazaar. “Just think of the great improvement a permanent wave makes in appearance. Close your eyes and imagine fairy fingers transforming your lank strands into lovely, lasting curls, as natural looking as if you were born with them.”

In reality, the permanent waving process involved fewer fairies and more fallible humans, who were tasked with winding hair tightly onto rollers, painting the strands with an alkaline chemical solution, and using fearsome-looking electric contraptions to blast each rolled-up section with heat from an individual metal cylinder.

When things went well, the client walked away with a soft set of waves cascading from the face. When things went poorly, the result was frizzy curls, broken hair, or a scalp burned red-raw.

The first permanent wave machines appeared circa 1906, courtesy of inventor Charles Nessler, who also went by the name Nestlé. Nessler’s device took advantage of a relatively new phenomenon—electric power—to heat up the hair. Strands were coated in a borax solution that broke the bonds of the hair, then wound onto heated cylindrical rollers. When the hair was cool, an oxidizing agent was applied to set the new wave. The whole process, which took place in a salon, lasted approximately 10 hours.

A permanent waving device shown in a 1912 edition of Popular Electricity magazine. (Photo: Public Domain)

The science behind this process was explained to the public in various ways, ranging from the dryly procedural to the delightfully evocative. In 1912, Popular Electricity magazine explained that the bountifully curly hair of children becomes lank and straight because the “tiny pores” get “clogged by a fungus growth as the years pass.”

Permanent waving, it declared, “produces the wave or curls of any style by removing the fungus growth from the affected straight hair, cleansing it and giving to it the beautiful texture as well as other advantages of natural wavy hair.”

Regardless of the details, permanent waving had taken off by the ’20s. The flapper decade brought innovations in hair-manipulating machinery, most notably the chandelier-style permanent wavers developed by Eugene Sutter and Isidoro Calvete in Europe.

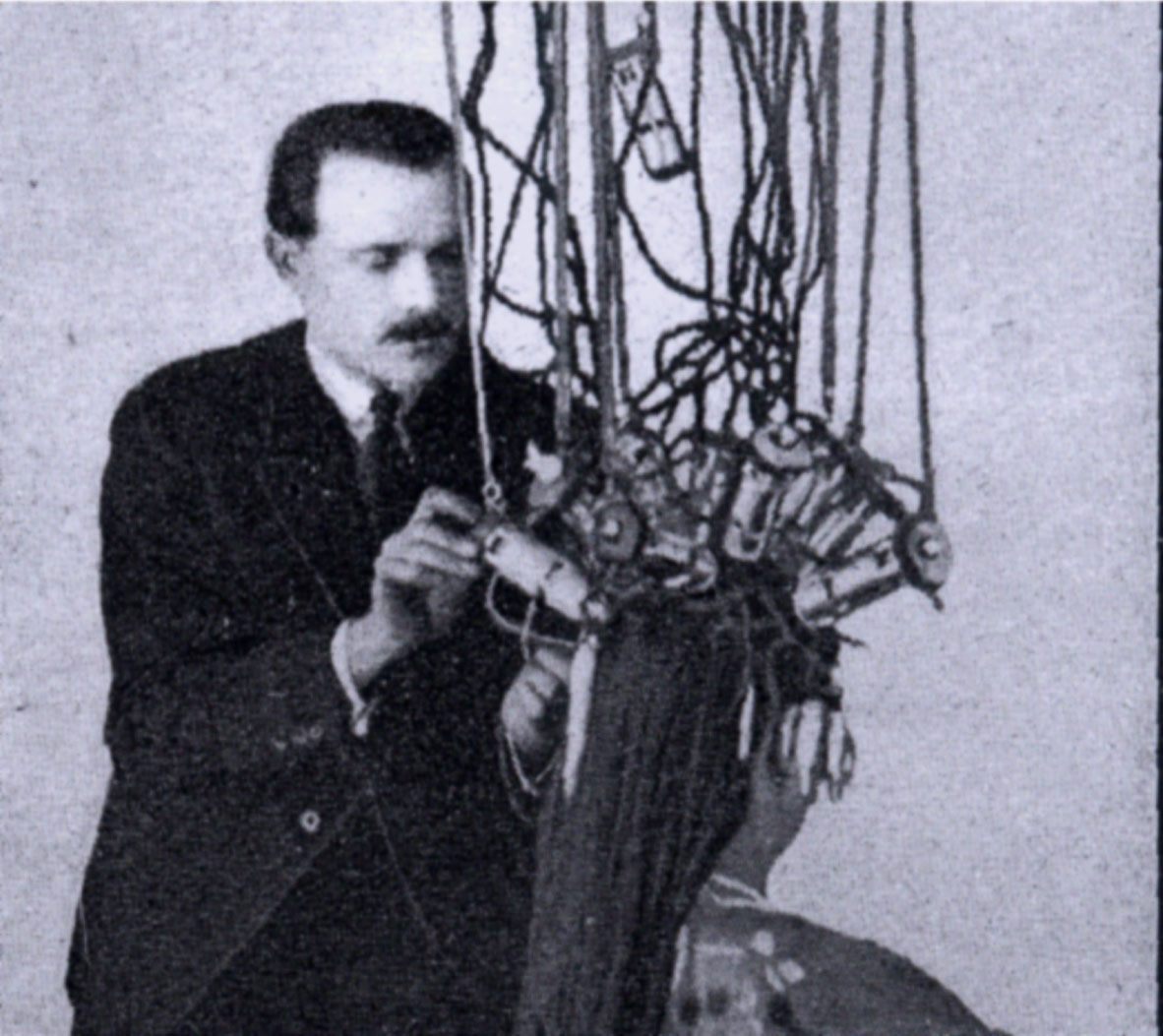

Eugene Sutter in the early ’20s, deploying a permanent wave machine designed by Isidoro Calvete. (Photo: Louis Calvete/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Salon clients whose chemically coated hair had been divided into sections and wound onto rollers would sit beneath a cluster of dangling cables, each of which had a metal cylinder on the end. The cylinders were secured over the rollers and the machine switched on, which delivered heat to each little tube. After four to 10 minutes of this head-cooking, clients would have their hair removed from the cylinders and washed to get rid of the chemicals.

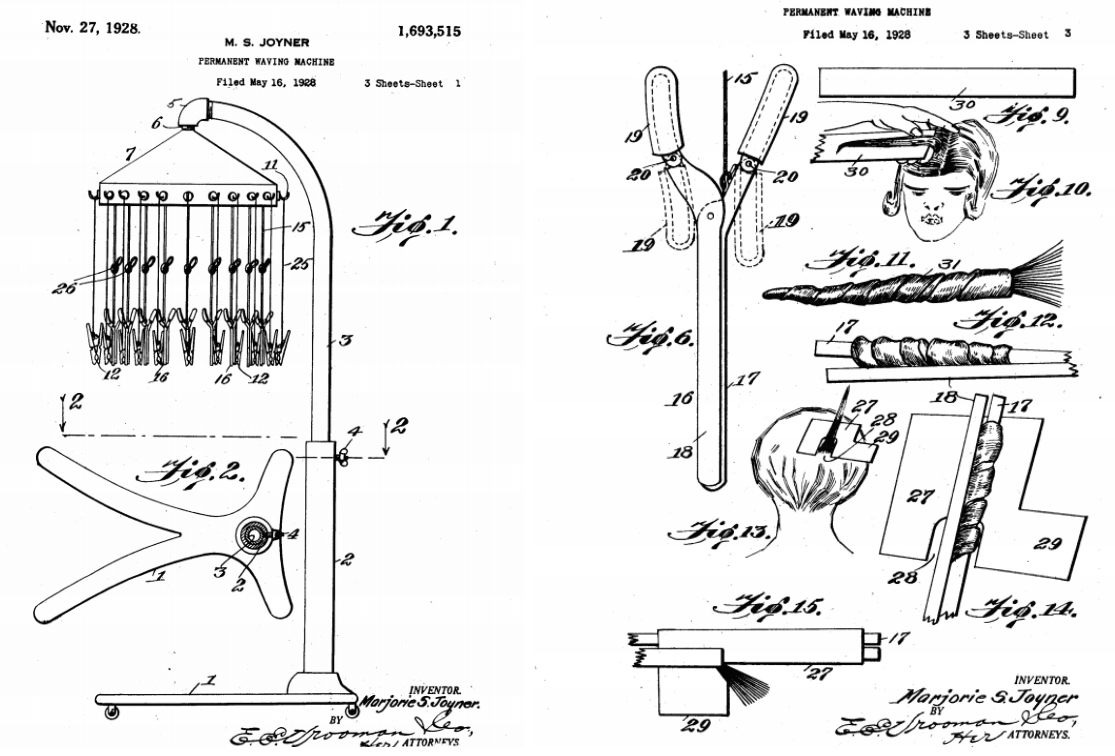

In 1928, the first U.S. patent for a permanent wave machine was granted to Marjorie Joyner, an African-American woman who had moved to Chicago to pursue cosmetology. Frustrated by the standard approach to waving black women’s hair—which involved a single curling iron and a lot of patience—Joyner came up with a more efficient method.

Marjorie Joyner’s 1928 patent for a permanent waving machine. (Images: Public Domain)

While making a pot roast one day, she stared at the rods that were holding the meat in place and heating it from the inside. Inspiration took hold. Joyner was soon hooking up 16 pot roast rods to a hooded hair dryer—her spin on the chandelier-style wavers coming out of Europe. The resulting machine, after a few design tweaks, received U.S. patent number 1,693,515.

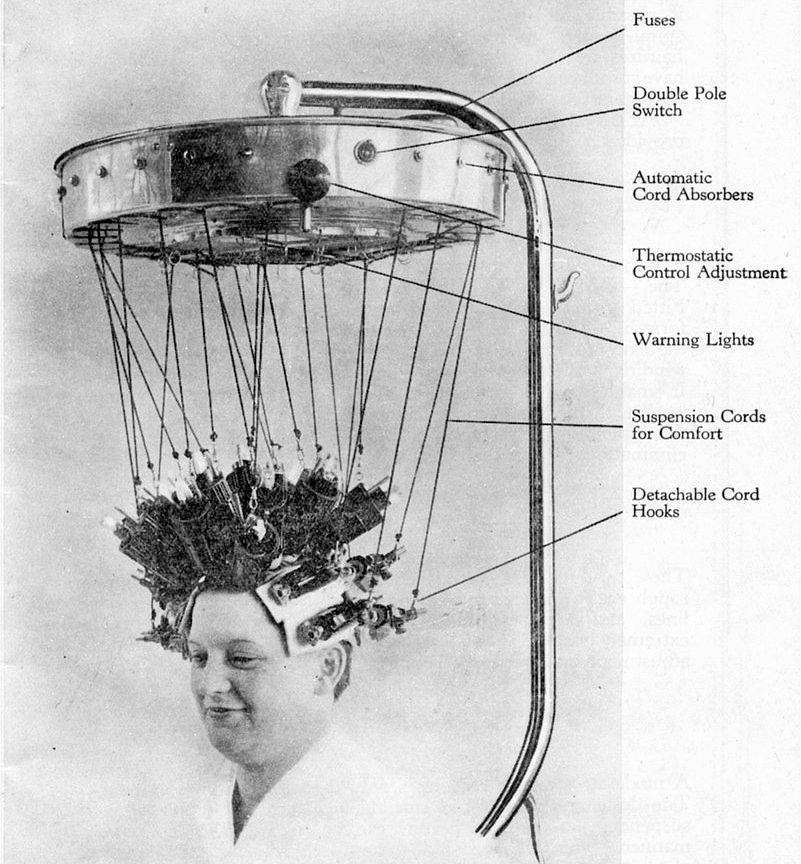

The chandelier-style machines may have been effective, but their aesthetics were a bit much for some. In his 1936 book Keep Your Hair On: The Care of the Hair and Scalp, Oscar Levin referred to the permanent wave machine as a “terrifying apparatus.” He was less critical of the protective non-conducting material used to safeguard the scalp: asbestos.

An Icall permanent waving machine from 1934. (Photo: Louis Calvete/CC BY-SA 3.0)

At the time Levin wrote his book, however, chandelier permanent wave machines were on their way out. A newly developed cold-waving perm process, which didn’t require heat, was beginning to take hold in salons. Not only that, home perming kits meant salon trips weren’t even necessary anymore.

By the time World War II had ended, the strange-looking perm machines were a rarity, and women no longer had to experience the indignity of looking like anthropomorphic hedgehogs suspended, marionette-style, by strings.

Object of Intrigue is a weekly column in which we investigate the story behind a curious item. Is there an object you want to see covered? Email ella@atlasobscura.com

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook