The Aurora Hunters Who Spend All Year Chasing the Lights

Aurora from Andoya island, Norway. (Photo: Arctic light - Frank Olsen/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Aurora from Andoya island, Norway. (Photo: Arctic light - Frank Olsen/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

When the sky turned red over Laramie, Wyoming, Todd Salat had never seen anything like it. Oh my gosh, he thought, it’s unbelievable. It was 1989 and he was seeing the aurora borealis, or Northern Lights, for the first time.

The aurora is typically not visible in Wyoming—as the name suggests, the lights are more visible the further north you travel. States that border Canada have a better shot at a lightshow than others and prime spots include Alaska, Norway, Canada and other high latitude locales during fall and spring. But in 1989 a massive solar flare made the lights visible even in tropical locales such as Cuba and Hawaii. Salat was hooked; he had to see it again.

Luckily, Salat, a geologist, had just landed a job in Alaska and a few months after his inaugural sighting, he was driving his truck down the Alaska Highway to chase an obsession that has lasted half his life.

Put in the simplest possible terms, the aurora is the result of charged particles from the sun colliding with atoms and molecules in the Earth’s upper atmosphere. When the particles and atoms meet, they emit light, and the dramatic, colorful aurora ripples across the darkened sky. There are two auroral ovals, around the south and north magnetic poles. In the south they are called (naturally) the Southern Lights or the Aurora Australis, and can be seen in spots such as Antarctica, New Zealand and Australia. Because the Northern Lights are visible over more populated areas, they are the most famous of the pair. The lights are often a vibrant green, but also glow pink, purple, blue and (as Salat saw) red.

Purple Aurora seen from Alaska. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Purple Aurora seen from Alaska. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The lights are captivating in a primal way—they connect those who gaze upon them to the edges of outer space. Getting a glimpse of them has become a common item on many bucket lists, and the tourism industry has been happy to oblige this urge. You can hop on the Aurora Express, operated by the Alaska Railroad. In Tromso, Norway tourists are ferried to ideal viewing spots and provided with warm booties, hot chocolate and sometimes reindeer meat. There is a photography festival in Tasmania and in Iceland you can combine aurora hunting with a dip in geothermal baths. You can even take a dogsled to the lights.

But Salat belongs to a more rarified group. He calls himself an aurora hunter and has dedicated his life to chasing the lights. After an initial stint in Alaska, he shrugged off his office existence and traveled around Australia and New Zealand, where he grew his hair long and had adventures (Spotting the Southern lights wasn’t one of them, but not for lack of trying.) Then he returned to Alaska—and the Northern Lights—for good in 1997. Salat makes his living photographing the lights and selling the images online and at craft markets and documents his travels on AuroraHunter.com.

Todd Salat on top of Murphy Dome just outside of Fairbanks, Alaska. He says the trick to successful aurora hunting is to dress warm and stay up all night long, for as many nights as it takes. (Photo: Todd Salat/AuroraHunter.com)

Todd Salat on top of Murphy Dome just outside of Fairbanks, Alaska. He says the trick to successful aurora hunting is to dress warm and stay up all night long, for as many nights as it takes. (Photo: Todd Salat/AuroraHunter.com)

The aurora is “sneaky,” says Salat. Even for scientists, predicting when the aurora will be visible is tough. It all depends on very specific atmospheric conditions and clear, dark skies. Luck and time are on Salat’s side, and he also uses online tools, such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration site, to keep track of conditions that might tip things in his favor. August through April are when he typically goes on photography trips (May through July are too bright for good viewing conditions) and he ranges quite far from his home base in Anchorage, sometimes straying over 800 miles to Prudhoe Bay in his camper. Salat’s wife accompanies him on some trips, but often he is alone and they call these excursions his “Lone Wolf Aurora Hunts”.

When Salat sees the aurora, he goes into a “zone” as the curtains of light buckle through the sky, convulsing in shockingly bright bursts.

“Imagine a solar wind racing through space a million miles an hour,” he says. “And then it gets into Earth’s magnetic field like a little baby’s breath puff, but that energy comes streaming down the magnetic field lines, collides with oxygen and—blamo!—photons of green lights, and there we are watching them swirling around like turbulence in a river.”

Looking straight up from Anchorage, the auroras create the breathtaking pattern known as the “corona effect” on August 23, 2015 at 12:40am. (Photo: Todd Salat/AuroraHunter.com)

Looking straight up from Anchorage, the auroras create the breathtaking pattern known as the “corona effect” on August 23, 2015 at 12:40am. (Photo: Todd Salat/AuroraHunter.com)

Over the years, Salat says he has seen the intererst in aurora hunting grow—sometimes he’ll show up at a spot to find more than ten photographers set up. And more an more, people ask him if he’ll lead them on a tour of the lights (which is not a service he offers).

The lights are beautiful, but they are also a force of nature. That 1989 event that dazzled Salat and other skygazers? It was the beginning of a solar storm that pummeled Earth. Radio communications were interrupted, satellites tumbled out of control, and Quebec’s power grid blinked off, leaving millions of people in the dark for about 12 hours.

With that in mind, scientists have joined pleasure seekers in hunting down these celestial events. Elizabeth MacDonald is a space physicist who works at NASA and is part of Aurorasausus.com, a project that is trying to harness the power of aurora hunters to better predict the lights, which will also help scientists better understand such (very rare) storms.

MacDonald first got the idea for crowdsourcing aurora sightings in 2011 when a particularly fantastic red aurora was visible as far as Alabama. She was a Twitter novice at the time, but knew people were talking about the aurora on social media, so she logged on and found a cascade of real time reports pouring in. A light went on: What if all those people were reporting their sightings to one place?

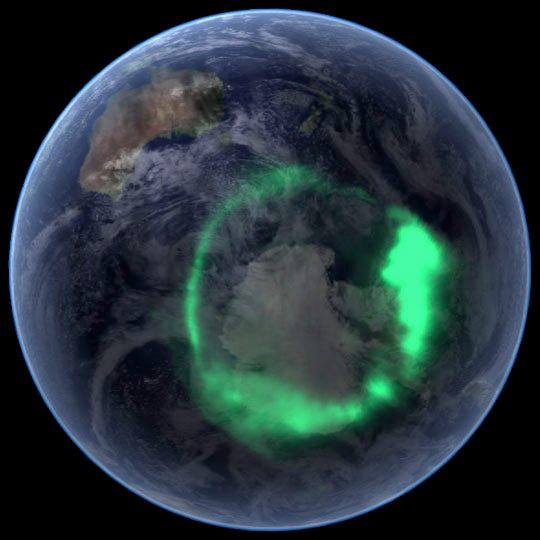

The Aurora Australis seen from space. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

The Aurora Australis seen from space. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

A trip to Aurorasaurus.com will reveal the project’s mascot—a friendly red dinosaur with green stripes that emit a very aurora-like light—and a map, which is the project’s key tool. The map pulls in user submitted reports as well as tweets to try and discern where the aurora is popping up in real time. Users are encouraged to help verify tweets—to sort out those that are actually about the aurora instead of, say, Aurora, Illinois. Through these efforts, Aurorasaurus aims to provide something that has been elusive—an aurora alert. Once sufficient reports have been accrued, Aurorasaurus (which can be downloaded as an iPhone or Android app) will send notices out to people in that area. The hope is to provide users some lead time, if even just an hour. The project, which is supported by the National Science Foundation and staffed with scientists, educators and volunteers, has over 2,000 registered users, including a core group of aurora hunters.

The project has arrived at a particularly opportune time—aurora visibility is on an 11-year cycle, and that cycle is currently peaking. Sun activity and other conditions are aligning to make the lights more visible at lower latitudes. A few large events this year have splashed the aurora across night skies as far south as Virginia and North Carolina.

Northern Lights seen from Finland. (Photo: Joni Räsänen/flickr)

Northern Lights seen from Finland. (Photo: Joni Räsänen/flickr)

MacDonald herself has seen the lights from Alaska (where she worked on a rocket that monitored the aurora) and from New Hampshire and Canada.

“Actually seeing them, it’s just amazing,” says MacDonald “They shimmer, they move, your jaw drops and you’re just staring at the sky thinking ‘Oh, my God.’”

Recently she made a trip to Yellowknife, Canada—a particularly good spot to see the lights from—where she accompanied a hardcore chaser on a trip, the kind of expert hunter whose arsenal of gear includes a tripod, camera, warm boots and a mug of Tim Horton’s coffee. The work of aurora chasers goes hand in hand with MacDonald’s scientific pursuits.

“You need to know when to get out of the truck and know when it’s going to be active,” says MacDonald. “That’s something that people who are expert aurora watchers really know quite a bit better than the scientists who sit in front of their computer screen and watch data coming down from satellites.”

For Salat, aurora hunting can be ecstatic.

“When I’m photographing, sometimes I call it ‘The Dance’— I’ve got a tripod in each hand and I’m spinning around and throwing my coat off. Even though it’s twenty below I’m sweating,” he says. “It’s just so exciting to get the shots.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook