The Best Sport Of The Early 1900s Involved Pushing Around An Elephant-Sized Ball

Invented by a football-hating electrical engineer, eventually, horses got involved.

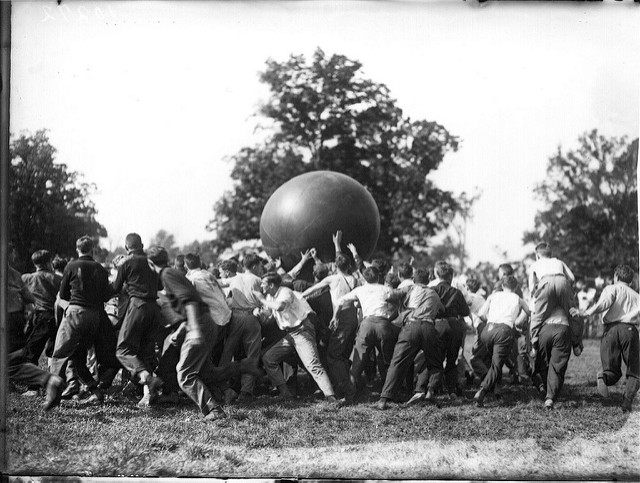

A freshmen vs. sophomores pushball game, at Miami University in 1910. (Photo: Miami University Libraries/Public Domain)

Imagine you’re touring the shed of an early 20th-century sportsman. It’s mostly standard stuff—tennis raquets and lacrosse sticks hang from hooks above the doorframe, and baseball bats lean against the walls. But over there, in the corner, something towers over the other equipment. It’s a hulking sphere, the size of a small elephant.

It looks like the boulder that chased Indiana Jones.

But this isn’t a weapon for squashing bad referees. It’s a pushball—the centerpiece of what might be the goofiest forgotten sport in American history. For decades starting in the 1890s, everyone from stockbrokers to college students had thrown themselves at a pushball, struggling mightily with his team to push it over their opponent’s goal line.

Pushball was the brainchild of a suburban Massachusetts man named Moses Crane. Crane made his living as an electrical engineer, selling telegraphs and burglar alarms from his Boston storefront. But much of his spare time was spent watching his three strapping Harvard sons play football, a sport he vehemently disliked. He was not the only one who felt this way: “The observer [of football] sees only a mass of struggling bodies piled up in a heap, disentangling themselves at intervals merely to repeat the unavailing onslaught,” wrote reporter C. H. Allison in a 1903 article celebrating pushball. “To the average person without a college education or a predilection for sports it is incomprehensible, dull, cruel.”

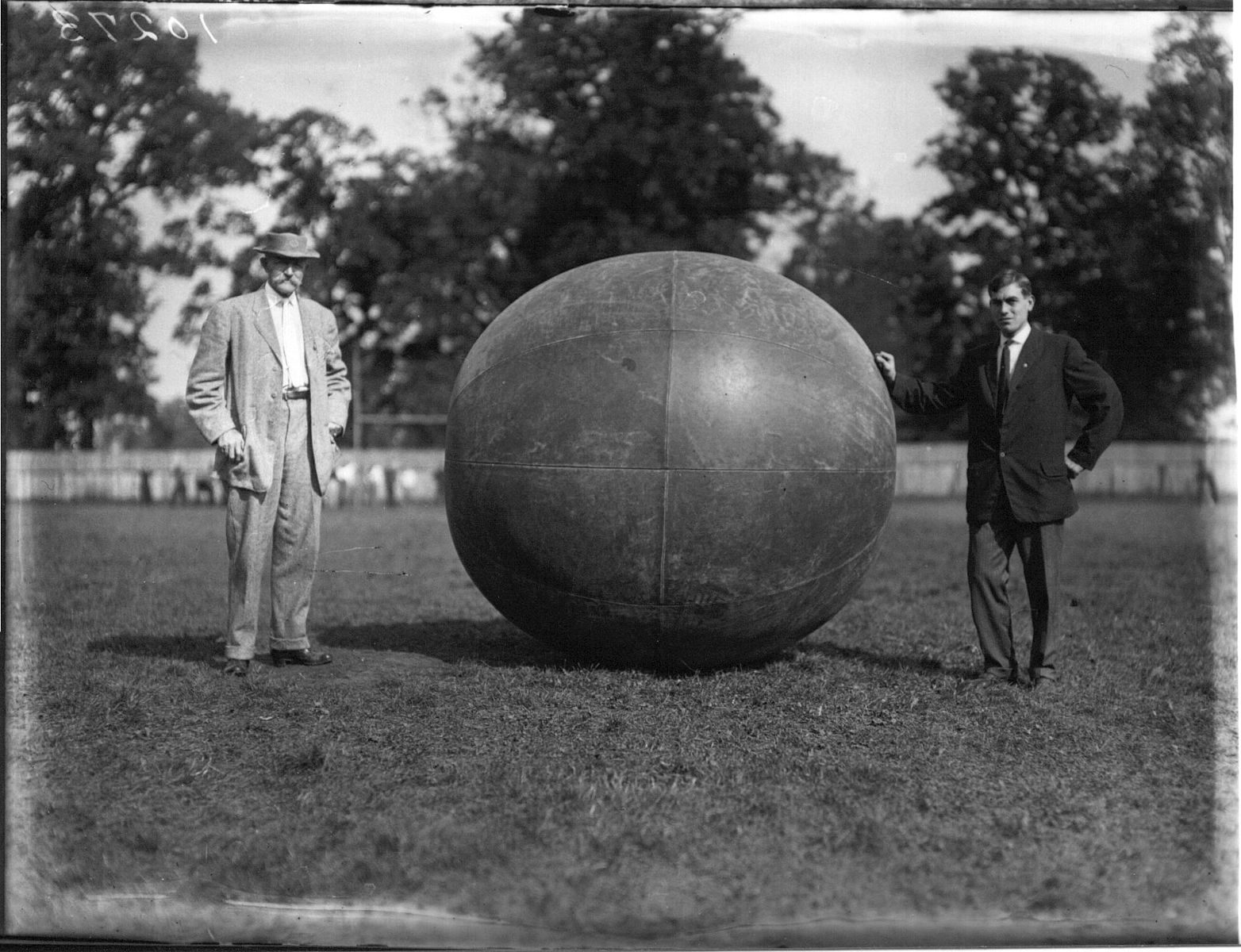

Miami University shows off its pushball. (Photo: Miami University Libraries/Public Domain)

Crane’s fix was simple: make the ball big enough that spectators could definitely, absolutely see it no matter what. After several years of offering this unsolicited advice, his hometown sporting club, the Newton Athletic Association, assured Crane that if he built such a ball, they’d find something to do with it. So in the fall of 1894, Crane constructed the first-ever pushball, out of rubber and leather and on his own dime (for $175, about $4,800 in today’s money). Six feet in diameter and weighing in at about 70 pounds, it was certainly unmissable.

Some Newton lads tested the massive ball out in a scrimmage just after Thanksgiving, pushing it around a field for hours and attracting a rather large audience. Local devotees worked out the rules over the course of the next year, and the sport’s official debut came in October of 1885, during the halftime of a Harvard-Brown football match.

“The object of the game is simply to push the ball,” explained a somewhat bemused New York Times sports reporter. “The game appeared very much a game for strong, active men, but was very amusing to the spectators.” A job well done.

Crane, who died in 1898, didn’t get to spectate many pushball games, and lacking his guidance, those who tried to introduce the sport outside of Boston ran into some logistical issues. One New York park manager, stuck without a pushball before a planned exhibition game, resorted to making one himself out of hay and shoe leather, and left it out on the playing field over a rainy night. When he let the players loose on it in the morning, the soggy boulder weighed, according to one chronicler, “closer to five hundred pounds.” The spectators enjoyed that game, too, but for different reasons.

Despite this and other setbacks, though, the sport eventually got rolling. In January of 1903, Spalding’s Athletic Library, a popular series of sports manuals, released a pushball edition, complete with illustrations, a brief history, and an official set of rules. Teams were to be made up of five forwards, two left wings, two right wings, and two goalies. The pitch was set at 120 by 50 yards, the same as a football field, with an H-shaped goal on each side.

Players scored points by getting the ball past the opposing side’s goal line—eight for hefting it over the crossbar, five for rolling it through the posts, and two for muscling it over the line at all, goal notwithstanding. And everything was done with a regulation-sized pushball, weighing between 48 and 50 pounds and produced (of course) by Spalding.

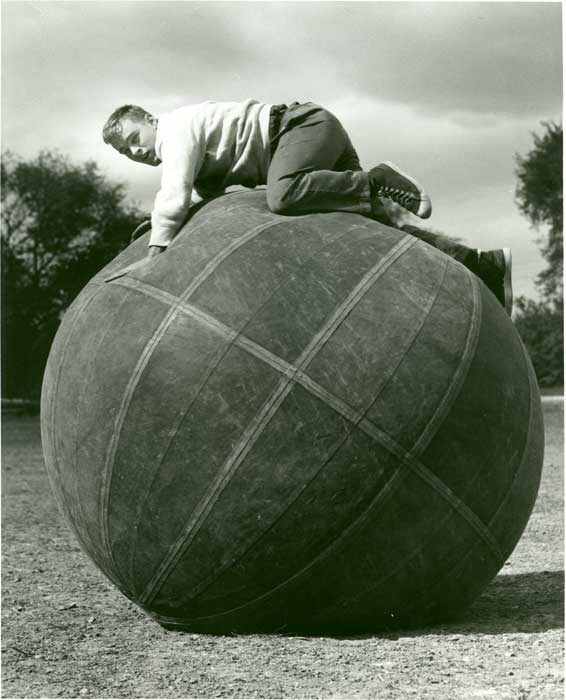

A player messes around at Washington & Jefferson’s annual pushball game in 1957. (Photo: Washington & Jefferson College/Public Domain)

Plenty of people have ideas about how to make sports better, and these days, few go so far as to implement them. But as sports historian John Thorn explains, things were different way back then. “The dawn of pushball [was] part of a ‘rage for sport’ that hit a prosperous America in the 1880s and spawned novelty contests galore,” says Thorn. Baseball was played on roller skates or ice skates, and goofy match-ups pitted every imaginable demographic against each other:one-armed vs. one-legged men, one department store’s employees vs. another’s, size-based “Jumbos vs. Shadows” matches.

Pushball had the advantage of being silly on its own. “It is an utterly ridiculous sport,” says Thorn. “It was jocular from the get-go.” Roll the behemoth game ball onto a field or into a room, and some kind of fun was inevitable. It was a favorite on various college campuses, where entire classes would rush the ball from either side. Starting in 1906, it was a huge part of the New York Giants’ preseason training regimen, replacing “the old-fashioned system of running and walking.” Wall Street brokers would break out a pushball as soon as the floors closed for Christmas. According to the New York Times, they labeled the ball “Amalgamated Copper,” and “pushed [it] up and down the floor much as the stock itself moves.”

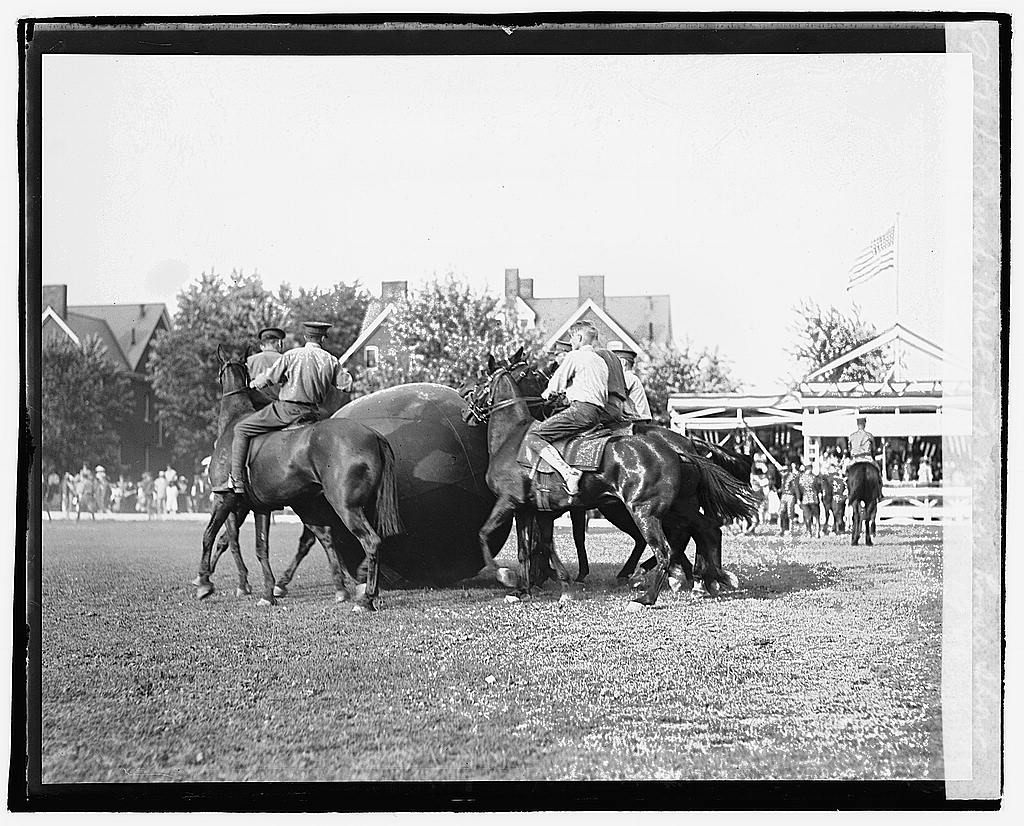

Horse pushball at the 1920 Fort Meyer Horse Show. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-npcc-02112)

Within a few decades of its invention, pushball was established enough that it, too, got the spinoff treatment. In the early 1900s, people started playing it on horses. “The ball is propelled by the horses knees, and an expert rider often makes his animal punt it the whole length of the field,” explains a description of a 1904 match, adding that this game was played “to the perturbation of several cows.” According to Thorn, by the 1920s, daredevils were attempting “auto pushball,” in which two teams of three cars went after the ball (“in it one gets many a thrill,” promised a newspaper ad). Meanwhile, says Thorn, the original sport was repurposed as a training exercise for soldiers who had been blinded in World War I, gaining it a bit of respectability.

But all good things must come to an end. By the middle of the 20th century, pushball had lost some of its momentum, replaced either by slightly more serious sports or even goofier ones. These days, you’d be hard pressed to find a pushball devotee, let alone a pushball. When asked to theorize on why the sport died out, Thorn mentions Sisyphus: “I think the existential pointlessness of the game had to dawn upon its participants,” he says. “You push this thing around, and then the time for your game is finished.”

You could argue, though, that it’s still better than football.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook