The Brilliant MI6 Spy Who Perfected the Art of the ‘Honey Trap’

During WWII, Betty Pack used seduction to acquire enemy naval codes.

Betty Pack on her wedding day. (Photo: Churchill Archives Center, Papers of Harford Montgomery Hyde, HYDE 02 011/Courtesy Harper Collins)

These days the “honeypot” is a popular trope in espionage thrillers, with seemingly every high-level informant recruited via seduction by a ravishing female spy. But long before James Bond ever jumped across the roof of a moving train in books or film, the globe-trotting spy Betty Pack was wooing suitors for classified information on both sides of the Atlantic. Few people have elevated the habit of pillow talk to an art form quite like the crafty American-born intelligence officer, who “used the bedroom like Bond used a beretta,” Time magazine noted in 1963.

Pack’s code name at the British spy agency MI6 was “Cynthia,” and her clandestine escapades during World War II led her boss, Sir William Stephenson, to call her unequivocally “the greatest unsung heroine of the war.” Her discovery of the French and Italian naval codes, as well as her work aiding in the decades-long effort to crack the Enigma code, helped the Allies stay a few steps ahead of the Axis powers, and eventually, win the war.

Amy Elizabeth “Betty” Thorpe was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 1910. She was an uncommonly restless child. “Always in me, even when I was a child, were two great passions—one to be alone, the other for excitement,” Betty told her fellow spy and lover Harford Montgomery Hyde, according to a new biography, The Last Goodnight. “Any kind of excitement—even fear.”

Betty Pack, spy. (Photo: Reprinted with the permission of The Baltimore Sun Media Group/Courtesy Harper Collins)

The rebellious girl worshipped her father, Colonel George Thorpe, and detested her mother, Cora. Though Cora was a highly educated and cultivated woman, from her earliest years Betty, who was equally brilliant, viewed her as little more than a striving socialite. “You might say that she was a Persian Cat and I was a Siamese,” Betty said later. As her father rose through the ranks in the military, the family moved to Cuba and then to Washington, D.C., where they hobnobbed with the political elite. Betty, sent to the best boarding schools, well-versed in high-society decorum, disliked the phoniness of it all. “Life is a game where one plays one’s role—where one always hides their true emotions,” she wrote in her diary at 13.

From an early age, Betty captivated many of the men she met. When she was only 11, an Italian diplomat named Alberto Lais became so infatuated with the child that he would disturbingly visit her at school, just to chat with his “golden girl.” Tall and willowy with blondish-auburn hair, huge green eyes and a soft, teasing voice, teenage Betty already possessed the sexual allure, heightened intelligence, and eye for detail that would make her such a successful spy.

“She had a force, or magnetism, to a terrifying degree,” Hyde recalled. This was only amplified when, during her high school years, Betty discovered her unabashed love of sex. “The greatest joy,” she wrote, “is a man and a woman together.”

At 19, she found herself pregnant and unsure of who the father was. In the circles in which she moved, being an unwed teenage mother was akin to social suicide. A desperate Betty quickly came up with a ingenious way to find herself a husband, and her child a respectable father. During a weekend party, she snuck into the bed of Arthur Pack, a dapper British diplomatic attaché twice her age, and waited for him to enter the room. “There she was in my bed,” Arthur would explain to his sister, “what could I do?”

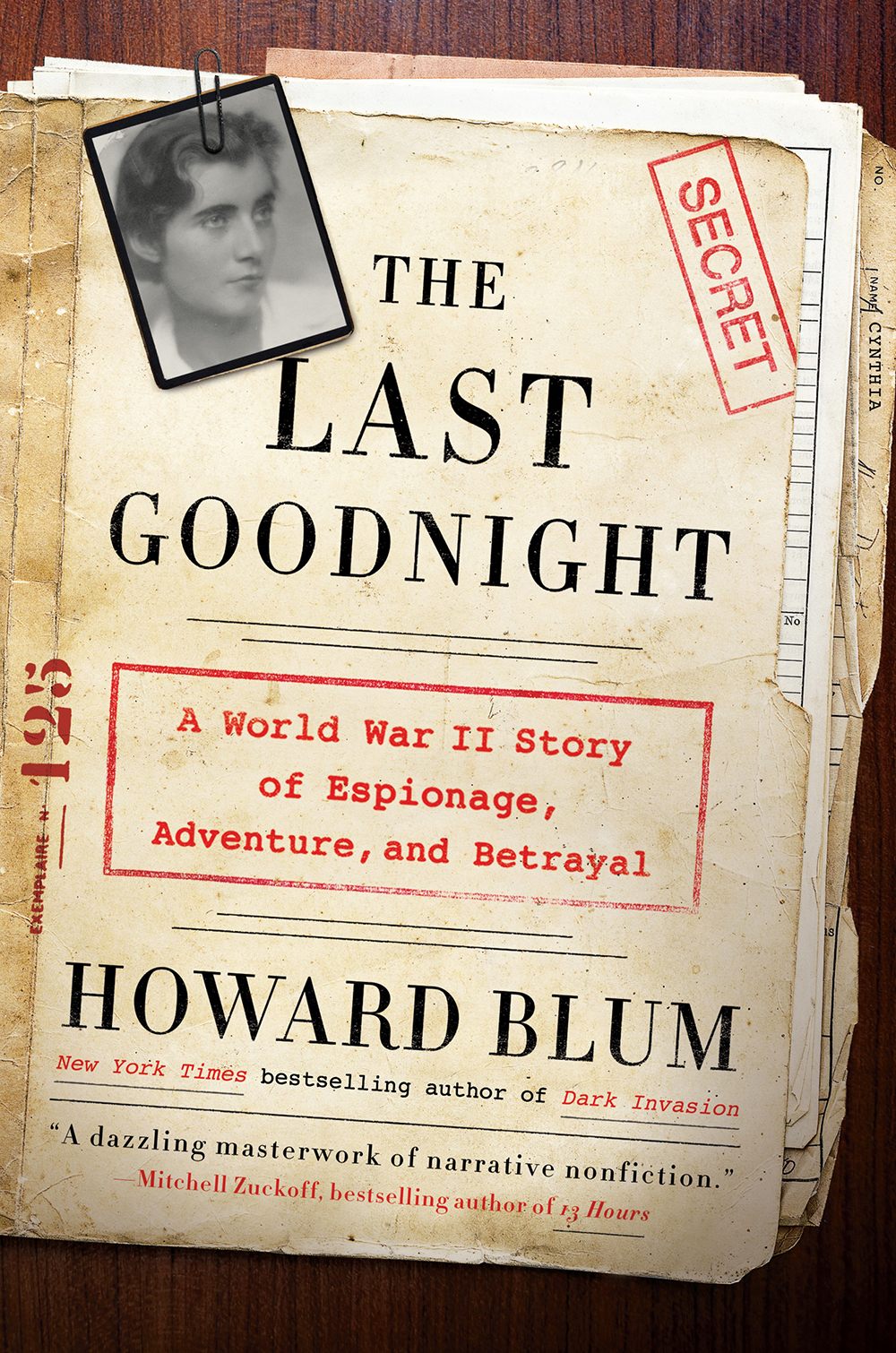

The cover of Howard Blum’s book The Last Goodnight. (Photo: Courtesy Harper Collins)

The couple were married in 1930. This would be the start of what Betty called her “vagabond years,” as she followed Arthur from diplomatic post to diplomatic post. However, Betty soon discovered that her husband was a cold man obsessed with his status. Fearing her child was not his, he forced her to give the baby boy to a foster family in England. From this point on, Betty knew she could never love the man who had taken her child from her, and began to pursue extramarital affairs.

During her husband’s postings in Chile and Spain, the trilingual Betty, often bored and restless, played the part of an perfect diplomatic hostess, and began to hone the information gathering tactics that would later serve her so well. But it was Betty’s selfless—and self-directed—actions in Spain that first caught the eye of MI6 in London. In 1936, the election of a pro-communist government in Spain led to the imprisonment of the clergy, including a priest that Betty was intimately acquainted with. After figuring out which prison he had been taken to, she arranged a meeting with the papal nuncio, the diplomatic envoy of the Holy See, and persuaded him to push for the priest’s release. Although this was a risky gambit, it worked. Betty then arranged the priest’s escape across the border.

Spain exploded into civil war soon after, and many diplomatic families were moved to Biarritz, France. But Betty did not stay there long. When she heard that Carlos Sartorius, a Spanish aristocrat and government official that she was in love with, had been thrown in jail too, she returned to Spain to find him. Again, she was able to convince a skeptical bureaucrat to not only take a meeting with her, but take up her cause. She also petitioned him for the release of 17 imprisoned airmen.

On the same trip, Betty herself was initiated into unofficial spy work by the Valencia-based British diplomat Sir John Leche. After her intercession on their behalf, Sartorius and the airmen were eventually released. Work done, Betty departed Spain. “I come and go,” she explained. “No bones broken, and no hearts either, I hope.”

In 1938, the Packs headed for Arthur’s new post in Poland. But her husband was as cold and distant as ever, a man obsessed with appearances. Lonely and searching for passion and conversation, Betty began an affair with a bookish, cultured man working in the Polish Foreign Office. Soon, he began to share his worries about his homeland, especially the fact that Poland was secretly working with Germany.

Pack in later years. (Photo: Churchill Archives Center, Papers of Harford Montgomery Hyde, HYDE 02 007/Courtesy Harper Collins)

Betty, who had seen the dangers of fascism and Nazism during her years abroad, was concerned by what she heard, and went to the head of intelligence at the British Embassy, John Shelley. A short time later, Shelley officially brought Betty into the MI6 fold. From there on out, the young American expat would find everything she was looking for—excitement, intellectual stimulation, and a life purpose—in partnership with Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

Now Secret Agent Betty Pack was instructed to set a “honey trap” for handsome Count Michal Lubienski, chief aide to Poland’s foreign minister, Josef Beck. After meeting at a society party, the two soon became lovers. During this time, Betty would empathetically listen to his worries, and then go home and type up meticulous reports. These colorful, detailed briefs of conversations with various marks became a staple of Betty’s career, and were eagerly awaited by the folks at British Intelligence.

During her trysts with Lubienski, she copied the reports that filled his suitcase, and eventually learned that the Poles had cracked Germany’s fabled Enigma Machine, whose codes had stumped Europe for decades. Armed with Betty’s information, the British convinced Poland to share the findings. Alan Turing could not have built his famous computer to crack a later, more complicated version of the Enigma cipher without the assistance of Polish mathematicians.

Betty’s time in Europe soon came to an end, but not before a side mission to Prague, where she helped rob the office of Konrad Henlein, leader of the pro-Nazi Sudeten German Party. Betty smuggled out the stolen goods, including an invaluable map detailing Germany’s three-year plan to invade central Europe, in the same suitcase as her negligees.

The Packs’ next stop was back in Chile, where an increasingly restless Betty posed as journalist “Elizabeth Thomas,” writing anti-Nazi propaganda for the paper La Nacion. But soon she left her husband and small daughter behind for good, and returned to her childhood home of Washington, D.C., posing as a freelance journalist. Her superiors at British Intelligence encouraged this move, knowing that as a single working woman, Betty could infiltrate social circles with greater ease.

Sir William Stephenson, Pack’s boss, and who called her “the greatest unsung heroine of the war”. (Photo: Public Domain)

Thus began what Betty called “the happiest days of my life.” Betty’s new boss was Sir William Stephenson, who led the “British Security Coordination” (wartime Britain’s American intelligence arm). Betty chose a lovely house on O Street in Georgetown, which had a handy secret exit around the back for “discreet entertaining.” She was soon given a big assignment— to discover the Italian naval codes.

Betty’s family connections and blue-blooded background were instantly useful. The man the BSC wanted her to trap was none other than Alberto Lais, now Italy’s Naval Intelligence agent, and the man running Mussolini’s secret spy network in the U.S. Soon, Lais was telling his “golden girl” secrets as he stroked and petted her, but never consummated the relationship. Betty, with her expert communication skills, was able to lead their conversations into areas the British were interested in. Eventually, she was able to bribe a clerk for the books containing the Italian naval codes, virtually neutralizing the Italian Navy for the duration of the war.

Her next assignment would be her greatest triumph. Having had so much success with the Italians, Betty was instructed to infiltrate the Vichy French Embassy. Betty’s mark, press attaché Charles Brousse, a married, charming man with serious concerns about the Nazis, immediately became Betty’s one “complete love.” Still, she made her boundaries regarding fidelity clear: “I do not belong to you or anyone else, not even to myself. I belong only to the Service,” she told him.

Soon, Betty had recruited Brousse to the Allied cause. But he balked at one assignment— to steal the French naval codes. “There’s a war going on, and if you, who swear you love me, will not help me, then I will either work alone or with someone else who will help me,” she threatened. He soon acquiesced.

Chateau de Castlenou, a castle in the Pyrenees, where Pack lived later in her life. (Photo: Jeantosti/CC BY-SA 3.0)

To get the codes, Betty orchestrated a brazen plan. Over time, the couple cultivated the French Embassy’s night watchman, convincing him to let them use the building for late-night rendezvous. The couple had loud, passionate sex for weeks, with the watchman believing he was simply aiding two lovers. One night, after serving the watchman champagne laced with sleeping pills, they let in a man known as the “Georgia Cracker”—a safecracker. Their first and second attempts to rob the safe failed.

The night of the third attempt, sensing the watchman was on to them, Betty and Brousse stripped naked. Sure enough, the watchman burst into the room, only to be thoroughly embarrassed. That night the safe was opened with the aid of the “Georgia Cracker”, and the code books photographed and replaced.

The codes were a boon for the British and American military, especially in North Africa. It meant the Allies were always aware of the Vichy’s location and plans, giving them an enormously important tactical advantage in every area of warfare. “They have changed the whole course of the war,” a colleague told Betty.

Unfortunately, Betty’s intelligence career ended soon after she helped secure this huge coup. Her cover was blown by none other than Brousse’s wife. After discovering the two in bed together, she screamed that Betty was a spy for all to hear. No longer anonymous, Betty retired from “the service.” She and Brousse married after the war and moved to Chateau de Castelnou, a foreboding medieval castle in the Pyrenees Mountains. Though they loved each other, Betty remained restless. Without the excitement of spy work, or a known enemy to defeat, she felt rudderless and trivial, like the society hostesses she had despised growing up.

Shortly before she died of cancer in 1963, she was asked if she was ashamed of some of the things she had done. “Ashamed?” she scoffed. “Not in the least, my superiors told me that the results of my work saved thousands of British and American lives… It involved me in situations from which ‘respectable’ women draw back—but mine was total commitment. Wars are not won by respectable methods.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook