The California Town That Produced 10 Million Eggs a Year

And then went on to become the Arm Wrestling Capital of the World.

Egg gatherers at Armstrong’s Spring Hill Poultry Farm, 1897. (Photo: © Petaluma Historical Library & Museum)

Is Petaluma, California, the world’s most divided city?

On the one hand it is renowned as a hub of fragility and fluffiness, on the other it is revered for solidity and screams. The reason for this split personality is that Petaluma holds the distinction of being not only the Egg Capital of the World but also the Arm Wrestling Capital of the World.

The city’s divided self can be traced back to the mid-19th century when California proved a mecca to those seeking gold, adventure or, in the case of Lyman Byce, good health. Byce was a part-time inventor who had fled the inhospitable wastes of his homeland Canada in search of warmer climes. He had already invented a spring lancet, an acoustic telephone and a potato digger by the time he wound up in Petaluma in 1878. However it took the sweet California airs to inspire him with his greatest invention, the one that would transform his fortunes as well as those of untold billions of chickens.

Inventing the perfect chicken egg incubator was an innovation race in the late 19th century—think of how companies are racing to perfect the driverless car now. Hundreds of inventors were working on ways to make an efficient machine to grow and hatch eggs without the mother hen being present, thus freeing her to lay even more.

There was one problem, though. Incubators had a nasty habit of bursting into flames, destroying buildings and chickens alike.

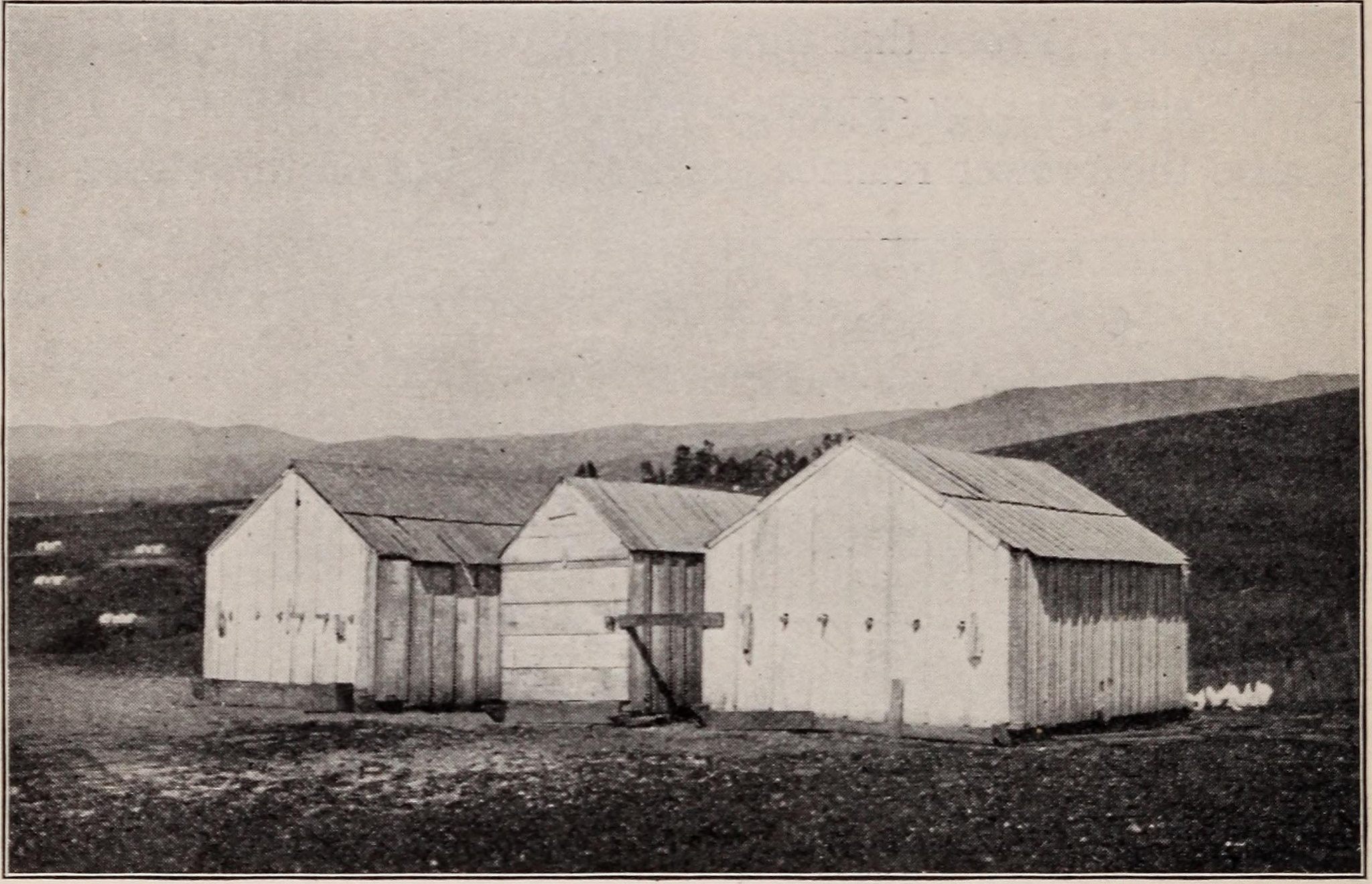

A Petaluma egg farm, c. 1913. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

This was not a new pursuit: the ancient Egyptians constructed large mud brick buildings in which to incubate their eggs. Heated by burning straw and camel manure, egg turners lived inside the malodorous structure, constantly assessing their delicate charges’ temperature by balancing the eggs on their eyelids. Later attempts used fermentation, hot water and steam to provide a constant heat to the eggs. However the inability to regulate the temperature accurately doomed them all to the inventor’s scrap pile.

It was a thorny problem and such backyard tinkering wasn’t always taken kindly. In 1881 the Petaluma Argus-Courier was aghast at a Petaluma chicken raiser using the heat from a hot spring to power his incubator. “If he succeeds,” worried the paper, “the devil will monopolize the chicken business. There are many things in this world that had better be done in the old way and hatching chickens is one of them.”

It took the tremendously mustachioed Byce to create a respectable incubator. His invention looked like a Victorian sideboard but was capable of maintaining a temperature of 103 degrees for a period of three weeks, so that the embryos inside the eggs could develop and hatch. Byce’s design won a medal for “Best Incubator” at the California State Fair and the Petaluma Incubator Company was born.

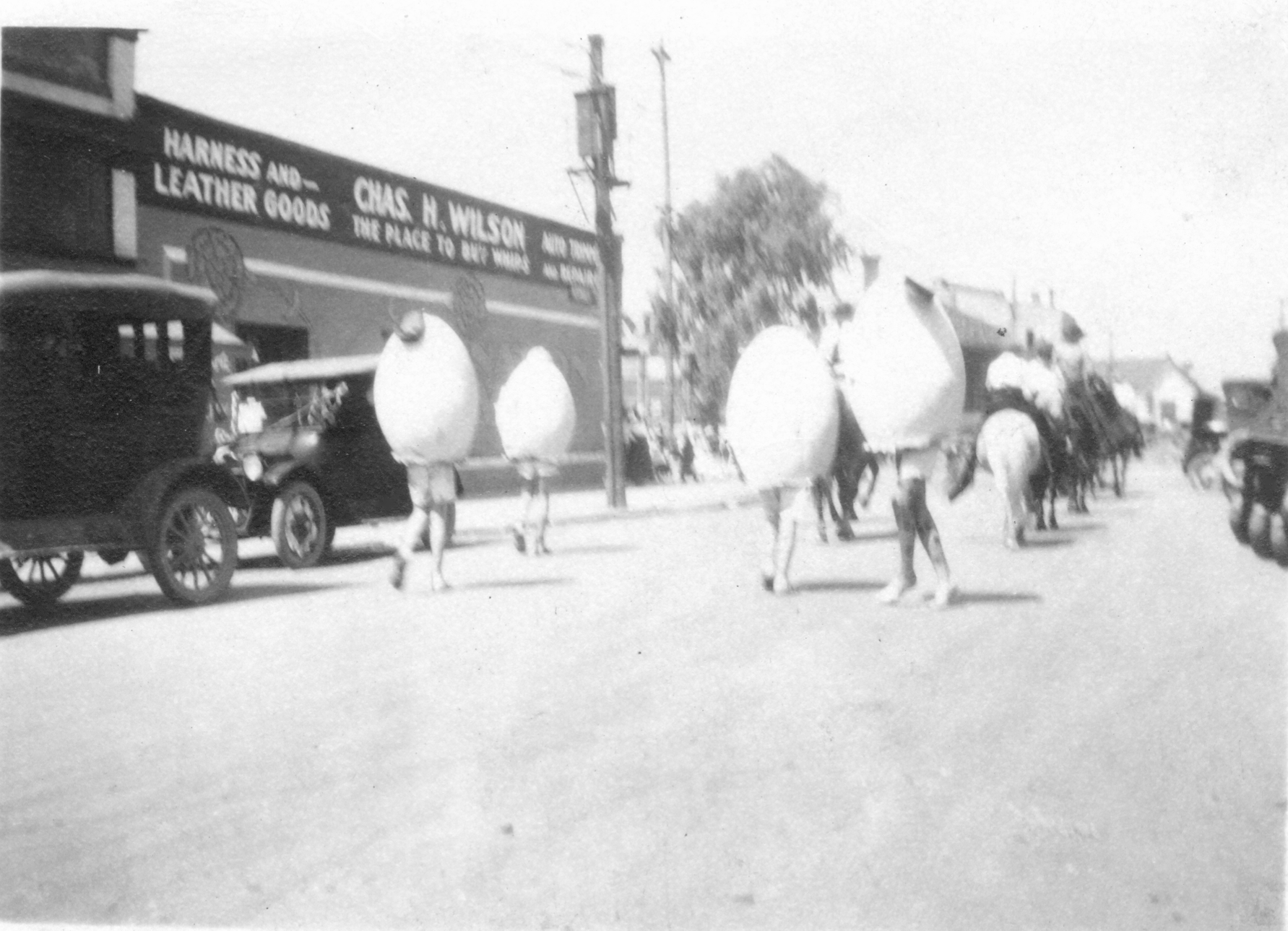

The Petaluma Egg Day Parade, August 20, 1921. (Photo: © Petaluma Historical Library & Museum)

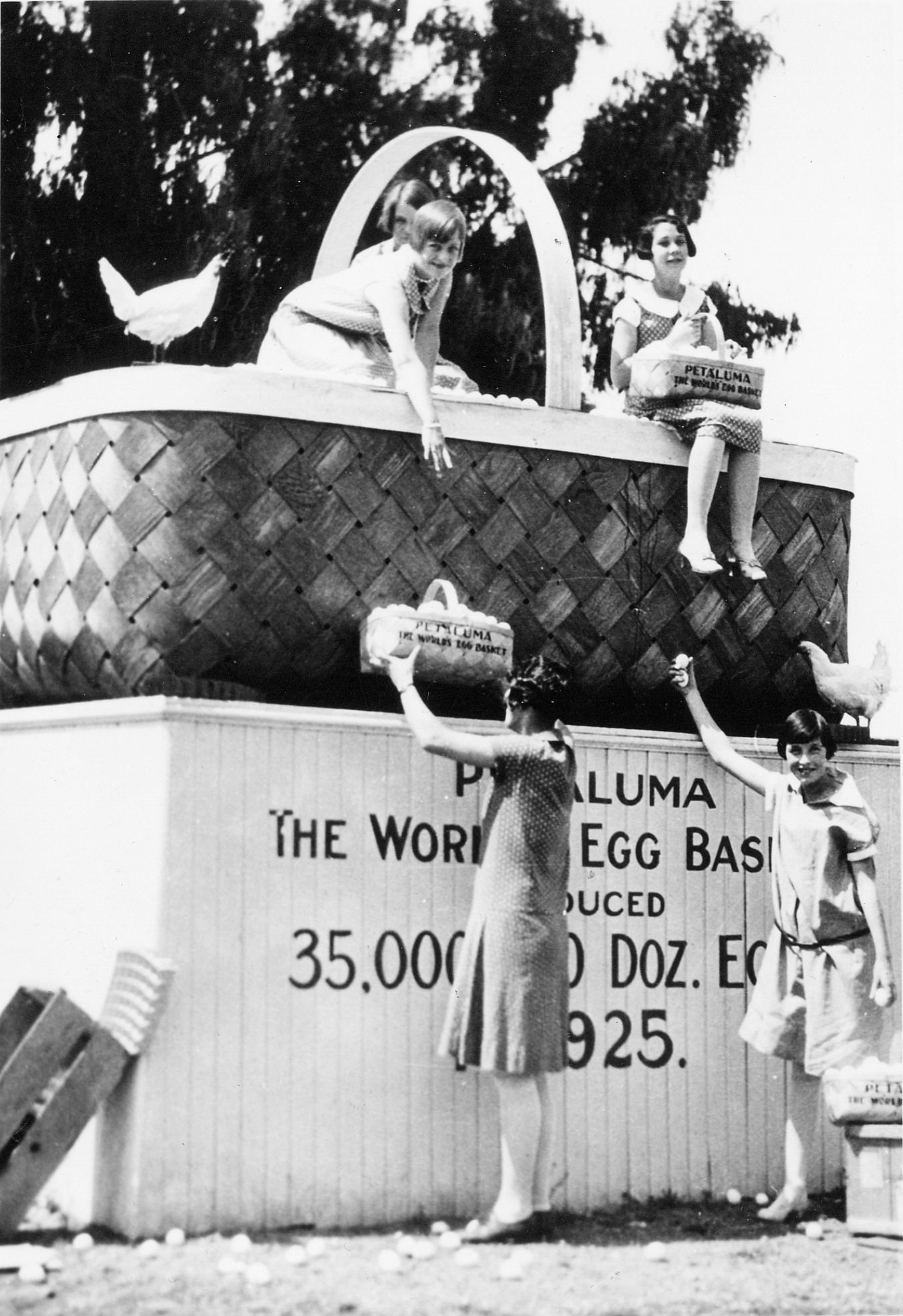

A photo from 1925 showing a giant egg basket, celebrating Petaluma as the “World’s Egg Basket”. (Photo: © Petaluma Historical Library & Museum)

By 1883, Byce had sold 200 incubators, mainly to small, family owned farms in the Petaluma area. Ten years later over 15,000 units had been purchased. When the highly productive Single Comb White Leghorn chicken was introduced to Petaluma’s chicken farmers — capable of popping out 200 eggs a year —there was no looking back. A park was named after the breed, as well as a baseball team and a statue of a chicken was erected in the town with the inscription: “The Kingdom of 10,000,000 White Leghorns — Petaluma.” Chickens were everywhere. A chicken pharmacy was even constructed downtown, a place to take your hens if they were feeling poultry.

By 1915 the town was producing an estimated 10 million eggs a year (at $.30 a dozen). With Petaluma being located next to a river and a railroad, the fragile eggs could be easily and safely shipped across the country. By 1918 the town was proclaimed “Egg Basket of the World” and a National Egg Day was held, with a parade led by the Egg Queen and attendant chicks. For nearly two decades there was more money on deposit in Petaluma banks, per capita, than any other town on Earth.

Buttons promoting eggs in the Petaluma Downtown Craft Mart. (Photo: Nicole/CC BY 2.0)

But a crack formed in the business. Improvements in caging and artificial lighting meant the clement California weather was no longer a necessity in raising hens, added to which advances in truck suspension meant eggs no longer needed to be carried by slow-moving railways or boat. Anyone, anywhere could start their own chicken farm. But out of the broken dreams of Petaluma’s shattered egg empire came a new birth. Whether it was due to the excessive amounts of protein in the local diet, or the frustrations at the city’s decline, the city was about to undergo a transformation into something less foul.

It began in 1955 with an overheard conversation in “Diamond” Mike Gilardi’s bar. Bill Soberanes was a local newspaper reporter struggling for stories in the depressed town when he heard a visitor boasting that he had never lost an arm-wrestling match—or wrist-wrestling as it was then known. With the inspiration of a journalist faced with a deadline he immediately saw a way to inject a little excitement back into Petaluma. The boastful visitor was Jack Homel, a trainer for the Detroit Tigers Baseball team, but Soberanes thought he knew just the guy to make him eat his words—Oliver Kulberg, a local rancher who was supposedly the strongest man in Sonoma County.

The match was set for February 16, 1955, a crowd gathered to watch the two men heave and strain. The contest went on for three painful minutes when, with a final shudder, the table collapsed. A draw was declared but from that day on an annual tradition was born.

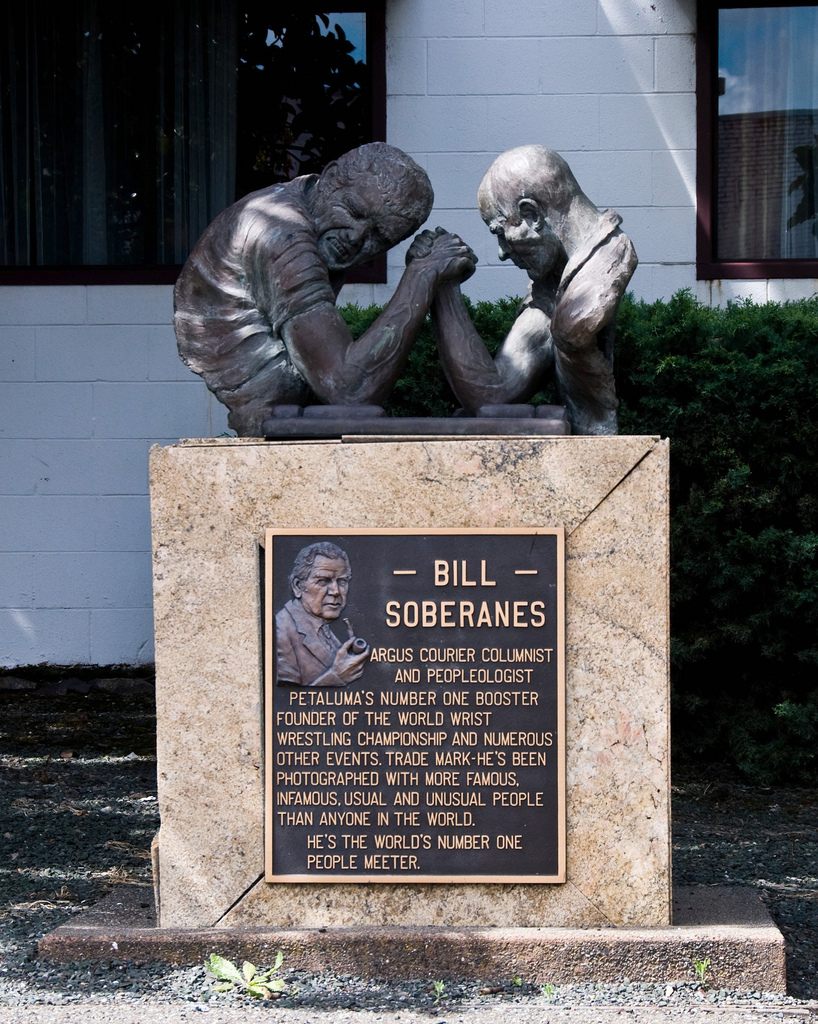

An arm-wrestling statue in Petaluma. (Photo: Tony Fischer/CC BY 2.0)

Of course arm wrestling was nothing new either. While the ancient Egyptians were incubating eggs in dung mounds, hieroglyphs show that they were also arm-wrestling with each other. Indeed the sport had been popular across the world for millennia since all that was needed of a competitor was one arm and a flat surface. What Petaluma did was transform this traditional sport into an organized competition.

By 1962 Petaluma’s annual bar event had ballooned into the World Wristwrestling Championship with the slogan, “Pure Strength and Raw Courage.” Fifty competitors with names like Earl “The Mighty Atom” Hagerman, and Duane “Tiny” Benedix wrestled it out in front of hundreds of cheering onlookers. The town was given an unexpected boost by Charles Schultz, the author of Peanuts, the most popular comic strip in the America at the time. Schultz lived near Petaluma and inserted the arm-wrestling competition into his strip. In the storyline Snoopy travels to the town to compete but is eventually disqualified for having no thumbs. Petaluma was soon proclaimed “Wristwrestling Capital of the World” and was a regular feature on ABC’s much-watched Wide World of Sports.

Behemoths such as Popeye-armed Jeff Dabe, and 385-pound Cleve “Arm Breaker” Dean, not to mention perennial champion John “The Perfect Storm” Brzenk, almost became household names. The success of Petaluma’s competition even saw Hollywood want to get in on the action with the creation of the classic 1980s movie Over The Top, starring Sylvester Stallone, although, ominously, its climactic match took place not in Petaluma but in Las Vegas.

For despite reaching its zenith in the 1980s, the sport of arm-wrestling was soon to abandon its spiritual home. The Annual World Wristwrestling Championship was held in Petaluma for the last time in 2002 before moving to Las Vegas. However a bronze statue still stands in downtown Petaluma, as the giant chicken statue did before it, depicting two men in a competitive grapple, grimacing, the veins on their arms bulging like giant caterpillars.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook