The Card Maker Who Brought the Joker Into the World

Samuel Hart introduced America to what would soon become the most annoying card ever.

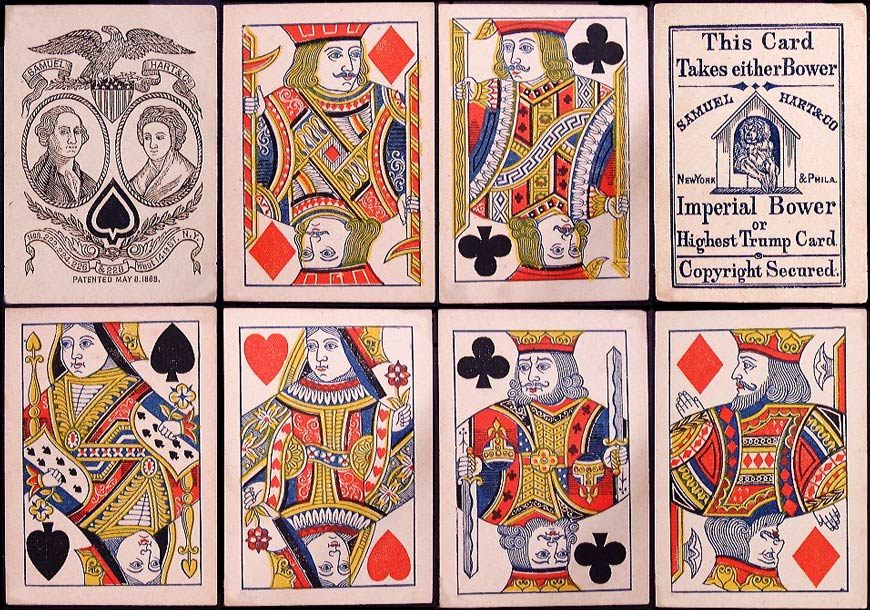

Some of the face cards without indices in one of Hart’s sets from the mid-1860s, including his new trump card. (Photo: Courtesy of World of Playing Cards)

Numbered cards, those make sense. The jack, king, queen—also logical. But a 19th century card maker named Samuel Hart re-shuffled the American notion of the card game by popularizing that bumbling buffoon we love to hate, the joker.

Hart is widely credited with having introduced the first illustrated joker-like card to the hands of players in the United States. Before the early 1800s, there just wasn’t a need for one. It took the game of euchre making its way into the American gaming repertoire before jolly jester was born.

In the game of euchre, traditionally the highest trump card—known as the “Right Bower,” an anglicized version of the German word Bauer, meaning farmer—is the jack of the designated trump suit, with the second-highest being the other jack, the “Left Bower,” of that same suit’s color.

But for the Americans, the game adapted to include a designated trump of trumps, and as its popularity skyrocketed, they started using blank cards around 1860 to create what they called the “Best Bower.” That’s where Samuel Hart is reported to have been a game-changer. In 1863 he released what is thought to be the first illustrated “Best Bower,” which he called the “Imperial Bower.”

Hart’s original “Imperial Bower” with the line of American jokers it inspired. (Photo: Courtesy of World of Playing Cards)

Euchre’s name almost certainly stems from the Alsatian card game Juckerspiel (pronounced with an English “y” sound) brought to the United States in the early 19th century by German immigrants. It also likely led to what would eventually became the name “joker,” according to Joshua Jay’s Amazing Book of Cards.

Euchre boomed in popularity within the ranks of Civil War soldiers, so much so that a Confederate soldier even noted that he and his fellow combatants would hear church bells, register that it was Sunday, and drop what they were doing, “even in a game of euchre.”

Civil War soldiers playing cards in their free time. (Photo: Library of Congress/Public Domain)

And so the joker was there to stay. Even as the commonly no-joker game of poker overtook euchre in fame, the pesky prankster could not be banished, due much in part to the work of Hart. Countless other manufacturers began incorporating it into their decks.

A pack of one of Hart’s “Linen Eagle” decks with square corners, said to have been manufactured by Samuel Hart & Co. in 1868. (Photo: Courtesy of liveauctioneers.com and Louis J. Dianni Antique Auctions)

A pack of one of Hart’s “Linen Eagle” decks with square corners, said to have been manufactured by Samuel Hart & Co. in 1868. (Photo: Courtesy of liveauctioneers.com and Louis J. Dianni Antique Auctions)Born in Philadelphia in 1818, Hart came from a long line of manufacturers. His family had worked in the stationery business since 1831, with his uncle Lewis I. Cohen having produced cards since 1832.

Hart opened up his first store in Philadelphia in 1844 and by 1849, he had opened up stores in New York City, and business was booming. He introduced the “Mogul” and “Steamboat” brands in the 1850s, which spread rapidly through the hands of many American players.

In 1854 Cohen handed over the reins of his manufacturing empire to his son Solomon and nephew John M. Lawrence, and 1871 saw the establishment of the New York Consolidated Card Company, a teaming up of Samuel Hart & Co., Lawrence & Cohen, and two more cousins named John and Isaac Levy. Hart’s name—bolstered by his renown and popularity—would appear on cards manufactured by the company until around 1915, long after his death in the mid-1880s.

But he didn’t just earn his reputation from introducing that divisive extra card.

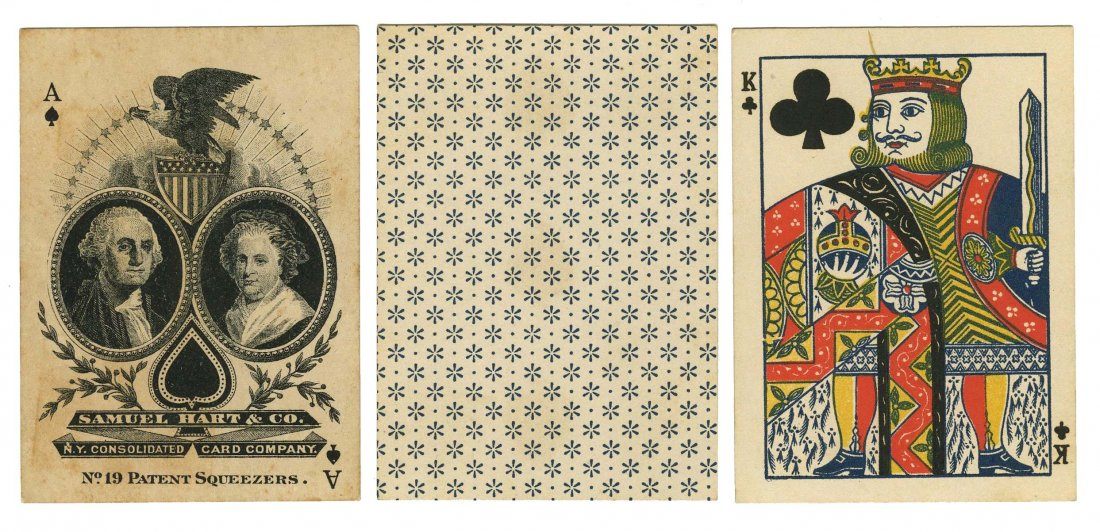

Hart’s “Squeezers” with corner indices. (Photo: Courtesy of liveauctioneers.com and Louis J. Dianni Antique Auctions)

Hart’s “Squeezers” with corner indices. (Photo: Courtesy of liveauctioneers.com and Louis J. Dianni Antique Auctions)

The now-commonplace glossy satin finishes and rounded corners didn’t always define gaming. Though Hart may not have been their inventor, he’s the one who brought them to the American public, making them standard in play. Most cards—even some of Hart’s earliest—were squared at the corners.

And he didn’t stop there. Mention a “squeezer” today, and you’ll likely get a host of blank stares. But in Hart’s time the newfangled innovation appealed to the hearts—and spades, clubs, and diamonds—of gamers and gamblers everywhere, as indices in the card’s corners allowed a player to “squeeze” his cards tightly together and still read their value.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook