The Century-Old Comic Strip Devoted to Cheese-Fueled Nightmares

The stuff dreams are made of: Welsh rarebit. (Photo: Fanfo/shutterstock.com)

The relationship between greasy midnight snacks and unusual dreams began logically enough–when Americans started staying up into the pre-dawn hours rather than turning in as the sun went down. Thanks to widespread artificial lighting, people in the 1890s could cavort until late, and they soon embraced a form of cheap drunken sustenance known as “Welsh rarebit”–essentially melted cheese on toast moistened with beer.

Not coincidentally, this was also the era when many carousers became acquainted with the bizarre realm of cheese-induced nightmares.

Winsor McCay, one of America’s most popular comics artists at the turn of the 20th century, was the self-appointed chronicler of this phenomenon. His daily strip, Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, did more than document, however. It was a stage where the secret fears, desires, and hypocrisies of modern life ran amok. Some argue that McCay, by plumbing the mundane and macabre workings of the unconscious mind, anticipated (or even laid the groundwork for) Freud’s popularity in America.

How exactly did Welsh rarebit become the snack of choice for American barflys? The dish traveled from England to the U.S. as a popular pub snack in the early 1800s, and circulated under many aliases: Welsh rabbit, Welsh rare-bit, and rarebit. Its ease and convenience suited the accelerating pace of life: Americans were “devoured with a passion for movement…always in a terrible hurry,” and thus they devoured rarebit.

Winsor McCay, author of Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, in 1907. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

McCay’s Rarebit Fiend showcased a familiar American type. Every strip recycled the same formula: someone eats rarebit, goes to sleep, dreams vividly, and wakes in a sweat, blaming the cheesy snack for their psychic ordeal. This gag reflected 19th-century popular psychology: such scientific authorities as Walter Cooper Dendy and William Hammond saw a straightforward link between indigestion and nightmares. Indeed, they considered dreams in general to be a byproduct of the body’s mechanical operations during sleep.

McCay jokingly positioned himself among these scientific investigators of dreams. He had read enough psychology to mock its literal-minded notions, as in his introduction to the first collected Fiend, where a made-up medical study correlated “visions of a distressing nature” with the “tensile strength” of cheese consumed. While spoofing the medical establishment’s unimaginative assertion that dreams were just mechanical background noise, McCay stealthily set forth his own alternative: dreams as a distorted expressions of deep-seated anxieties.

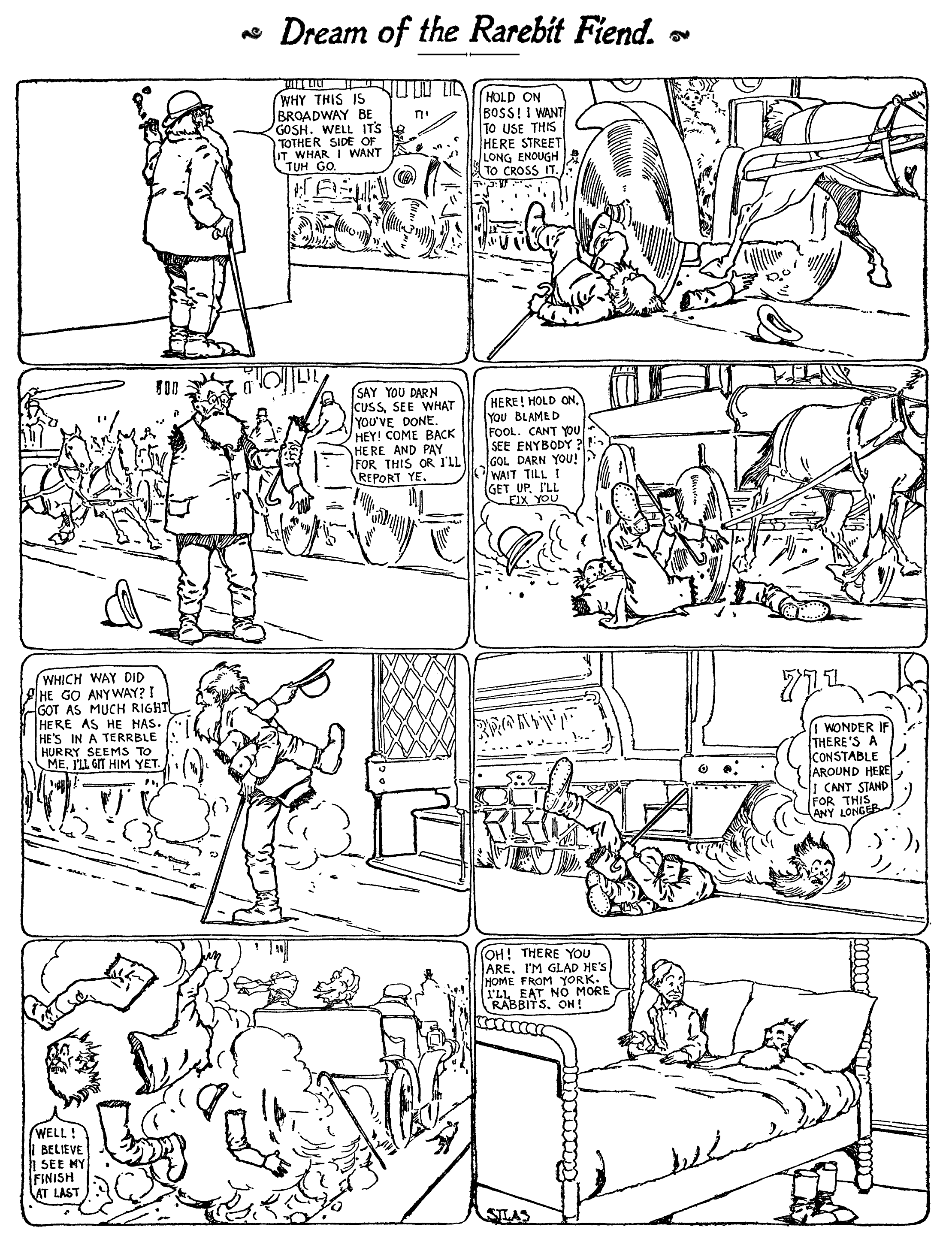

Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, October 26, 1904. A woman dreams that her husband gets run over while crossing Broadway. (Photo: Public Domain/Comic Strip Library)

For instance, a strip from October 26, 1904 (above) begins with a man crossing a busy New York street. In each successive panel he gets hit by a fast-moving vehicle and loses another limb. He continues to hobble across the street until finally smashed to bits by a motorcar–a country bumpkin literally annihilated by the speed of the city. The last frame reveals whose nightmare this is: a panicked woman sits up in bed, the man from the dream asleep beside her. His boots on the floor indicate his recent return from a journey. “I’m glad he’s home from [New] York,” the man’s wife gasps, and swears off eating Welsh rarebit.

McCay constantly blurred the line between entertainment, journalism, and science. When discussing the Rarebit Fiend, he insisted that “I merely tell the story, like any other newspaper reporter…One newspaper artist is sent to a big fire, another to a banquet…I am assigned to illustrate the rarebit dream of some poor unfortunate in Hoboken, N.J.”

Always a showman, McCay postured as a beat reporter for comic effect, but he did, in fact, collect ideas from his readers, some of whom he credited in his strips. Massive collections of data came into vogue around the turn of the 20th century, and newspaper readers would recognize echoes of psychologist G. Stanley Hall’s popular questionnaire method. Jumping on the bandwagon of optimistic reformers who hoped to perfect society through statistics, McCay declared that his enterprise “is no joke, satire, or burlesque: it is… illustrated and published for the public good.”

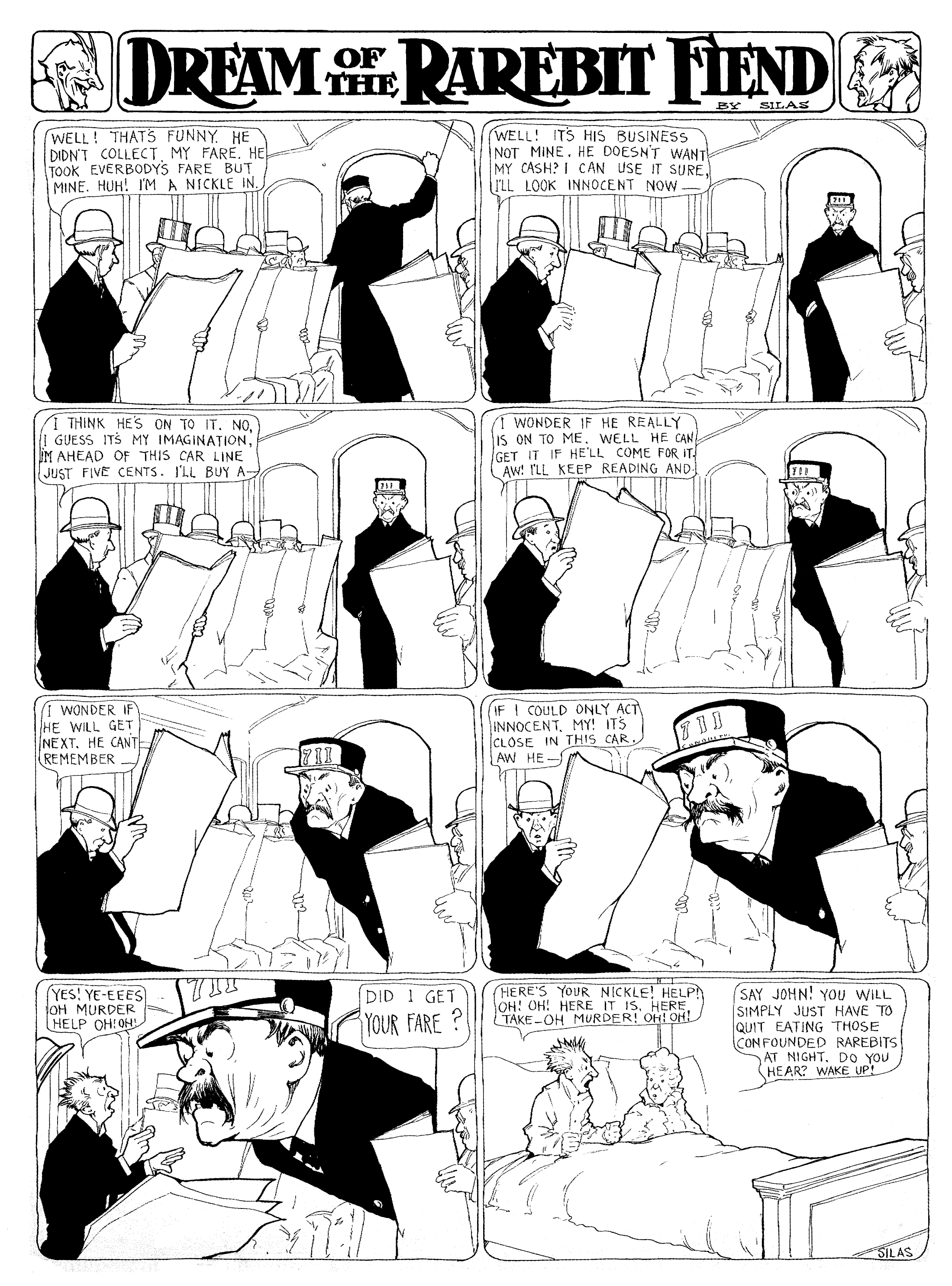

Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, August 31, 1905. A man tries to evade paying his trolley fare. (Photo: Public DomainComic Strip Library)

In his capacity as a dream expert, McCay portrayed his strip as a window into the nation’s unconscious. Even if his tale of mailbags overflowing with rarebit dreams was just a publicity stunt, the Fiend pioneered a practice of public dreaming. The fantasies and terrors inside the ordinary American’s skull played out what comics scholar Jeet Heer calls “the quintessential Victorian theme of bourgeois hypocrisy.”

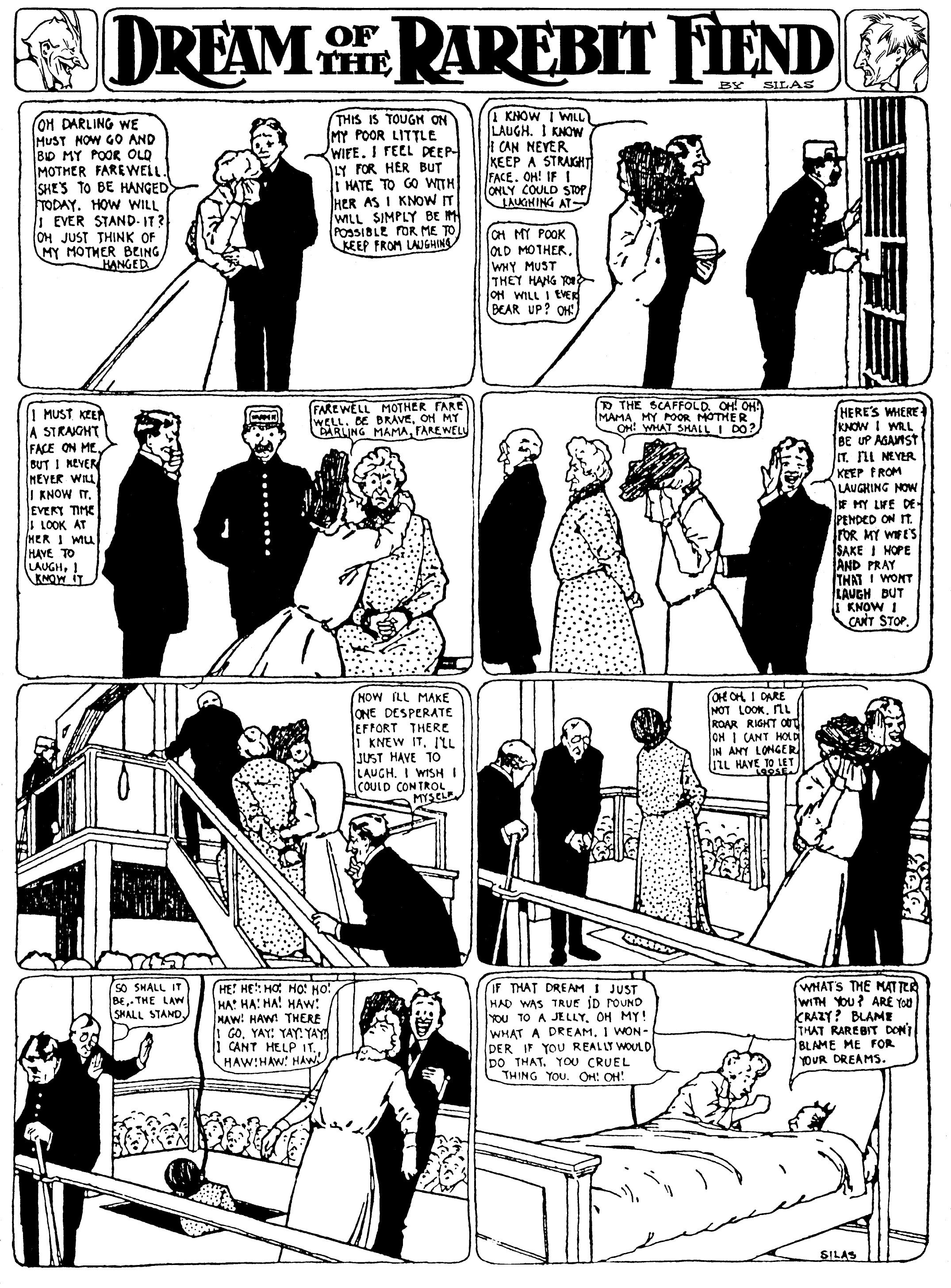

In a 1905 strip (below), a young wife dreams that her mother has been sentenced to death, and her husband can’t restrain himself from laughing as his mother-in-law drops from the gallows. For McCay, the mechanical relationship between mind and gut was just an excuse to showcase the dark psychological relationship between dreams and secret desires.

Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, May 6, 1905. A woman dreams that her husband laughs hysterically at her mother’s execution. (Photo: Public Domain/Comic Strip Library)

Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, May 6, 1905. A woman dreams that her husband laughs hysterically at her mother’s execution. (Photo: Public Domain/Comic Strip Library)

Winsor McCay’s most significant dream was a failed one: from early childhood he longed to become a great painter, but he spent his life toiling for a salary as a quick-draw illustrator. He began painting signs for dime museums as a teenager and took up newspaper work the 1890s. His job was to churn out drawings on a deadline and he produced at a breakneck pace, documenting the disasters and scandals of Gilded Age New York City.

The birth of the Rarebit Fiend in 1904 coincided with the death of McCay’s high-art aspirations. “I woke up,” he confessed, “from a dream which lasted–well, as long as I can remember. It was a dream that I was to be a ‘master’.” Instead of composing timeless masterpieces in oils, McCay inked cartoons in a mechanical frenzy, at a pace that his colleagues deemed inhuman. He promoted the image of himself as a human drawing machine. Asking his art director for a raise, McCay explained: “You know what to do to a thrashing machine to make it run better? Grease it.”

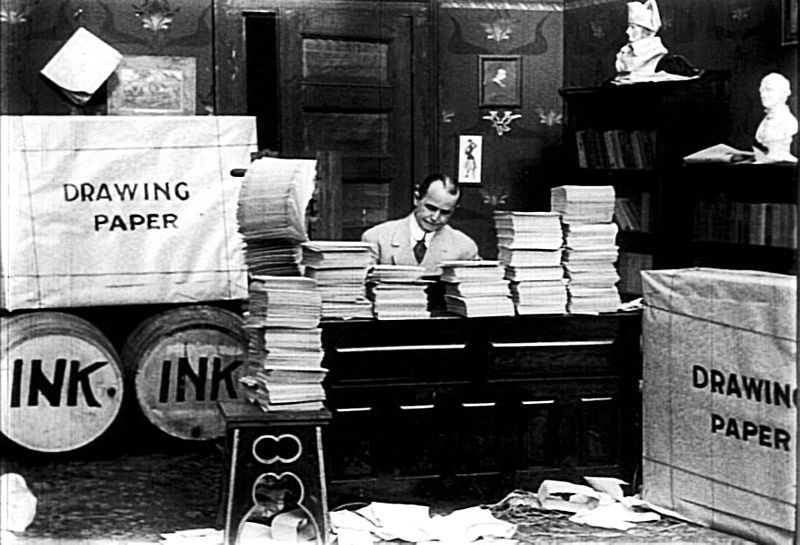

This grinding, factory-style work was well-suited to the demands of early animation. In 1911, McCay produced one of the first animated films, Little Nemo, which was comprised of over 4,000 hand-drawn frames. A live-action prelude sets up the story: McCay bets his skeptical colleagues that he can complete the monumental task in less than a month. Then we see a montage of workmen hauling industrial-scale drawing supplies into his office. Dwarfed by giant ink barrels and towering reams of paper, McCay looks like a creature out of his own comic strip. It’s hard to tell whether he’s in the clutches of a newspaper cartoonist’s dream or nightmare.

Still from Winsor McCay’s 1911 film, Little Nemo. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

If McCay was a machine, he was fine-tuned to channel the clamor and chaos of industrial cities. Mocking romantic tropes of artistic inspiration, he claimed that the concept for Rarebit Fiend came from New York’s noise pollution: “About a year ago, when nothing disturbed the calm morning air except the noise in the street, the machinery in the building and the yells of the other employees…my brain gave birth to a tiny idea.”

The Fiend was a fun-house mirror reflection of the American psyche at the dawn of the twentieth century. With distorted logic that fused the laboratory, the vaudeville stage, and the factory, McCay challenged the mechanical model of dreaming with a psychological one.

In August of 1909, when Sigmund Freud stepped off an ocean liner in New York City, Americans who read the funny pages were better prepared for the shocking arguments of psychoanalysis than their peers who stuck with the stock market reports.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook