The Decapitated Saints Who Still Managed to Hold Their Heads Up

Saint Justus (Photo: Rubens/Wikimedia)

This is part three of a three-part series on decapitation. Previously: zombie dogs’ contributions to neurosurgery and headless cockroaches that just won’t die

Saint Justus was nine years old when his head was cut off, for being a Christian in 3rd century France. Later, during the 18th century Revolution, the French would learn that a head, once severed from its body, might twitch and even retain a sliver of consciousness for a few seconds, and there is a bit of truth to that. But Justus’ head went far beyond that.

Justus’ body picked up his head, which spoke. Just a few words of prayer. But that, not surprisingly, freaked out the soldiers who had killed him, and they fled. Justus’ father found his son’s body in this state, sitting, with its head in its lap. And then the head spoke, again, asking that it be brought to his mother, who should kiss it. His head, Justus seemed sure already, would become a holy object, worthy of veneration.

As head-carrying saint, Justus has good company. St. Denis, of Paris, is considered the most famous, for carrying his head the six miles from Montmartre, where he was killed, to the spot where his basilica, the resting place of French kings, would later be built. His head preached the whole way there. There’s also Ginés de la Jara, who threw his own head in the Rhone, and Winifred, of Wales, whose head rolled down a hill and was later reattached to her body.

But these are just some of the most well-known of the head-carriers. In total, there are more than 120 such “cephalophores,” who are martyred by beheading and yet do not die. (At least, not immediately.)

Christian saints are not the only Europeans whose heads have kept on living after they were separated from their bodies, though. An earlier Celtic culture also had a fixation with heads, and some stories about pre-Christian Celts feature talking, severed heads, as well. Which has raised a natural question: Did the stories of headless Christian saints grow from an older Celtic cult of the head? Or did they arise independently?

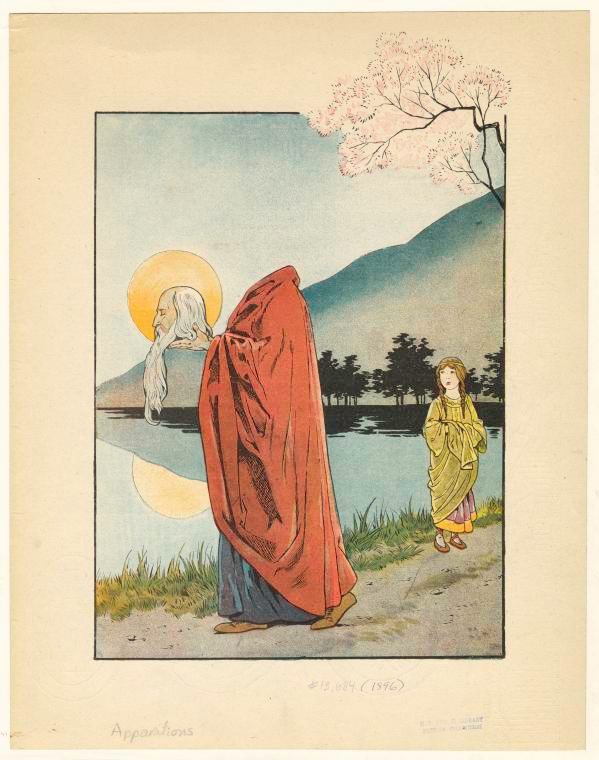

There are more than 120 head-carrying saints (Image: Public domain)

Christian saints are far from the first or last people whose headless bodies have been endowed with life, or whose severed heads have retained the power to speak. In Greek myth, Orpheus’ head, torn from his body by the maenads, continued to prophesy. In Welsh sagas, Bran’s head asks that it be buried in a certain place in London, but before it’s in the ground, entertains and guards his warriors through a decades-long feast in the Otherworld. In the 14th century story of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Sir Gawain strikes of the Knight’s head, which the body picks up and rides away with it. And the dullahan, the headless fairy rider of Irish mythology, has its own American incarnation, in the headless horseman of Sleepy Hollow.

It seems like the connections are everywhere. Can it really be a coincidence that the Irish also tells stories of headless fairy horsemen—and that the tradition of jack o’lanterns comes from the same location? Are turnip heads and jack o’lantern pumpkins there to keep us safe from the Otherworld, on the night when demons come close, just as Bran’s head kept his warriors safe? Are these all versions of the same story, passed through different places and times?

How to wrap one’s head around headlessness?

It is tempting to connect St. Justus and the other headless saints to an older, Celtic tradition concentrated on the power of the head and linked to Christianity in the same way that midwinter festivals were linked to Christmas. But there’s a strong argument that the stories of headless saints are entirely independent, born specifically to root Christian head relics in particular religious centers. Possibly, people just that obsessed with heads—that they’ve independently dreamed up living, headless figures, with talking heads, over and over again.

Headless horsemen, less saintly (Photo: The Lamb Family/Flickr)

Scott Montgomery, a medieval art historian with an academic sideline in psychedelic rock posters, first started thinking about cephalophores when he was working on his dissertation on head reliquaries, the religious containers for the bones of saints. In the course of his research, he came across one very unique reliquary in which the saint is holding his head out, away from his body. He thought it was anomaly, until he kept finding more stories of headless saints.

Many of the stories, he found, had a similar structure. Like St. Denis, other cephalophores take their head and they carry it to their site where their relics will eventually stay. It’s a simple story that does a lot: it shows the power of the saint over death, it shows resurrection, and it puts the saint’s relics in a very specific place.

“I started to think about how so much of the art of the Middle Ages was driven by the desire to make real this incredibly difficult notion that the bones of a saint are the most potent power there is,” he says. “I ended up interpreting the form as a means of enlivening the relic. You pop a skull on the altar and tell people that this is the presence of the saint. It’s a stretch.”

St. Denis (Image: Job/NYPL)

A walking headless body might seem outlandish, but it does explain why a head relic is there. And, Montgomery found, usually the stories came from the monastery or church that presents the relic.

In his view, there’s no connection between these stories and stories from Celtic culture that also feature severed heads. Part of the problem with making that connection, he says, is the geographic distance between the two types of stories and the timeline on which they spread. “We have zero of evidence of anyone knowing those stories [of Celtic severed heads], which are isolated to the western parts of the British Isles, before we have cephalophory emerging in Italy and France,” he says. “The places that cephalophory evolved were not connected to the places where these other stories were popular.”

The only reason he sees to connect Celtic headless stories with Christian headless stories is that otherwise, you’re just talking about a story that the Catholic church promulgated and that helped solidify its power in particular places. “Take the Celtic cult of the head away, and it seems unsexy,” Montgomery says. “There’s nothing more unsexy than the Catholic church.”

At Reims (Photo: Mattana/Wikimedia)

There is some evidence that Celtic cultures, which spread across Europe and into the British Isles until Roman conquest, a few hundreds years before the first millennium A.D. began, had were unusually interested in the head. In a couple places in France, archaeological sites have produced sculptures of disembodied heads and religious installations with niches intended for skulls. Reports from Romans (which, like those from any conquering culture, are not to be completely trusted) portrayed Celtic warriors as head-hunters.

And then there are the stories. Perhaps the most famous and most compelling is Bran’s. A virtuous king, he led his warriors into battle in Ireland, to rescue his mistreated sister from her husband. Eventually, he is wounded, but before he dies, he instructs his surviving warriors to cut off his head and bury it back in Britain. His head, severed from his body, continues to speak, and guide the warriors. They end up feasting happily for 80 years, in the Otherworld, while the head entertains them. It’s only when one warrior forgets the head’s instruction not to open a particular door that the feast ends and the warriors are returned to the regular world and forced to confront their loss.

For many years, scholars considered stories like this one as guides to the pre-Christian world of the Celtic culture, even though they were not written down until centuries after the time period in which they’re set. The actual evidence of Celtic religious beliefs, though, is thin, and more recently scholars have become more skeptical of how much these sagas can actually tell us about the distant past. And any connection to Christian stories about headless saints is somewhat tenuous, beside the obvious one that there are talking heads involved.

Celtic art, with skull niches (Photo: Rvalette/Wikimedia)

What connections there are, between the distant past and the stories about that time, and between Christian and pre-Christian stories “have to be viewed with great care,” says Marion Löffler, a scholar at the University of Wales and managing editor of Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. But there are scholars who aren’t ready to dismiss the possibility that there is a common thread.

One intriguing line of inquiry, she says, focuses on Ogmios, a Celtic deity. One of the most striking descriptions of this god portrays him with chains threaded through his tongue and to the ears of his followers. Often this is interpreted as indicating his eloquence—the power of his head to talk and influence the heads of others. “It has to be treated with great caution. But it was a head. which was obviously very eloquent and able to connect to his listeners. This may, just may be the connection, with vital head and severed heads in early Christian Ireland and medieval Wales, as in the tale of Branwen ferch Llŷr, which features the severed head of Bran.”

Regardless, headless saints in the British Island do have their own particular spin on decapitation. A handful, like Winifred, have their heads put back on. One scholarly interpretation of that trope is that it’s a counterargument to the warrior culture that prevailed before Christianity. Yes, heads are important. But even better than being a talking head: being a head that doesn’t need to survive on its own.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook