The Delights and Perils of Navigating New York City With a Guidebook From 1899

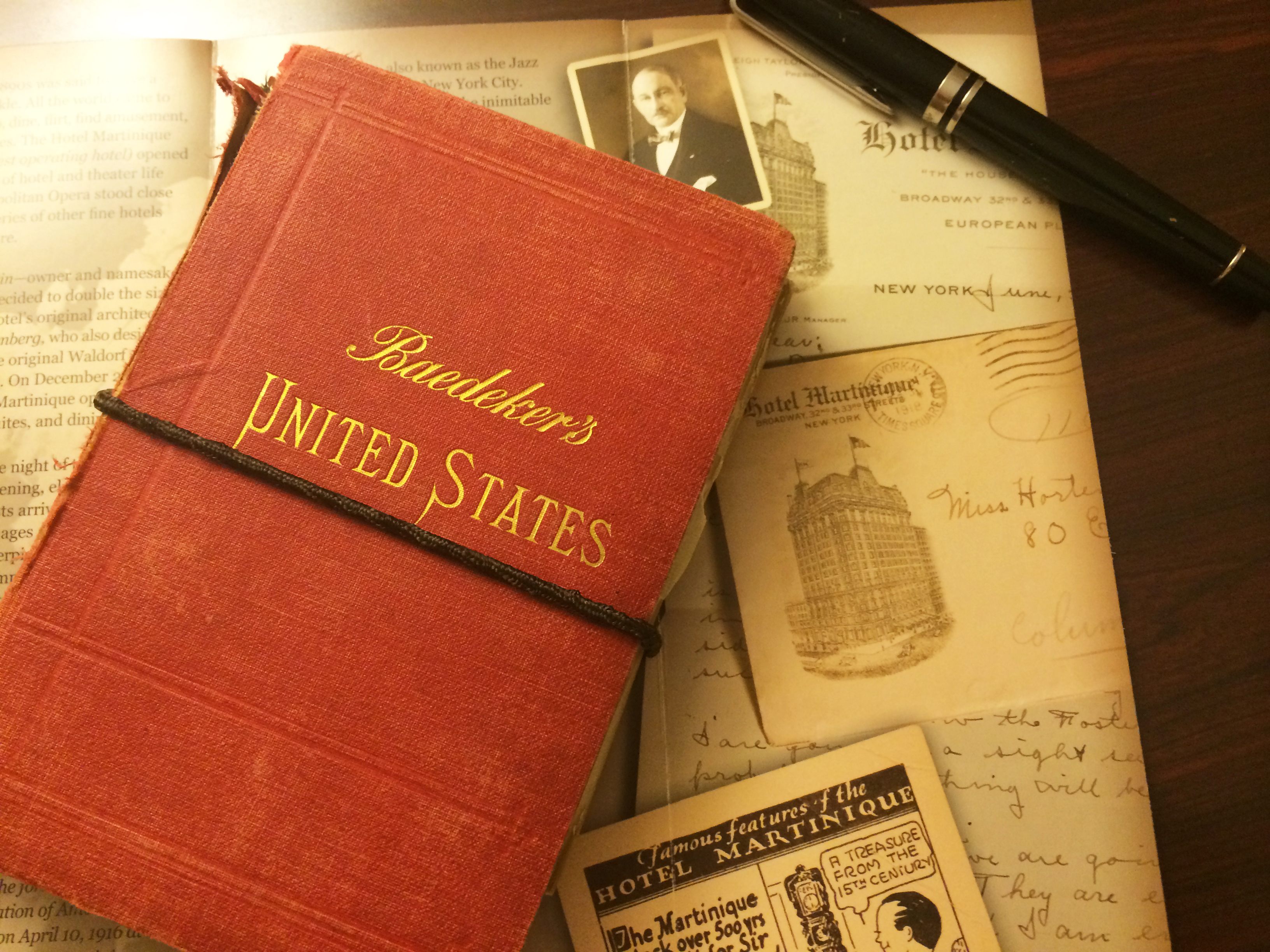

Luke Spencer’s Baedeker’s United States Guide, at the Hotel Martinique, which opened in 1897. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

A century before the travel guide shelves at bookstores were bursting with Lonely Planets, Fodor’s, and Frommer’s, there was just one book for the discerning solo explorer: the Baedeker guide.

Established in 1835 in Germany by Karl Baedeker, these pocket-sized books were intended for the well-to-do gentleman traveler. With their maps, restaurant recommendations, and practical information on international cities, Baedeker guides proved hugely popular among independent travelers of the 19th and early 20th centuries. But could an adventurer use one today? To find out, I spent a weekend exploring New York City, directed solely by the fourth edition of the 1899 Baedeker guide to the United States.

One of the pioneering features of the Baedeker guide was bespoke chapters written by experts on subjects like local history, customs, geography, arts and sports. Travelers could read up on these during the sea voyage over, to help create a picture of their destination.

Karl Baedeker, c. 1861. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The portrait of America painted by my Baedeker wasn’t exactly promising:

“The average Englishman will probably find the chief physical discomforts in the dirt of the city streets, the roughness of the country roads, the winter overheating of hotels and railway cars, the dust, flies, mosquitos of summer and in many places the habit of spitting on the floor.”

Standing at the foot of Broadway, about to venture into the city, I was nonetheless heartened by Baedeker’s caveat: “The Americans themselves are now keenly alive to these weak points and are doing their best to correct them.”

Karl Baedeker pioneered guide books including travel information and lists of notable sights, essential for the new class of 19th century explorers. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

The first order of business was to secure suitable accommodations, in which, ideally, no-one would be spitting on the floor. Many of the grander hotels listed in my guide still exist today, including the Waldorf-Astoria (“$2.50 per night”), the St. Regis (with its fine library of 2,000 volumes), and the Gotham (today known as the Peninsular). These “fashionable houses of the highest class” are still as they were back then, “sumptuously equipped and decorated with large ball rooms.”

I selected the Hotel Martinique (“good cuisine”), located on Broadway and 32nd Street. It is a beautiful Beaux-Arts building designed by Henry Hardenburg (who also created the Waldorf-Astoria, the Dakota and the Plaza), and still features its original 18-story spiraling staircase and elaborate mosaic tile floor, but sadly not its in-house theater, known as the Dutch Room, after its resident vaudeville act the Dutch Room Girls.

Safely ensconced in my room, it was time to see what the Baedeker recommended for dinner. It offered the following helpful advice on New York fare:

“Oysters are large, plentiful and relatively cheap. Wine is generally poor or dear [expensive], often both. Ladies without escort are not admitted to the best restaurants in the evening.”

Browne’s Chop House on Broadway and 39th, a few blocks away from the Martinique, sounded intriguing (“good cuisine, interesting dramatic pictures”), but is now sadly a Pret-a-Manger with hardly any dramatic pictures at all. A few blocks further down on 36th by Herald Square, though, Keens Steakhouse is still very much thriving.

In the Baedeker, Keens gets a one-word review: “Men.” When I stopped in to dine on their traditional famed mutton chops in the old bar room on a Friday night, this was still largely the case. There were very few women to be seen. The chief difference between now and then would have been the smoke; Keens kept around 90,000 members’ clay pipes, which today are still hanging from the ceiling, but can no longer be smoked indoors due to New York’s 2003 ban. In the 1890s, there was also a door to the Garrick Theatre next door, and according to legend, actors in full costume would rush in between acts for a swift chop and glass of ale.

Keens, home of the largest collection of churchwarden pipes in the world, and its famous mutton chop since 1885. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

In the 1890s, the principal form of evening entertainment was the theater. Today we think of the theater district as being centered around Times Square. But in the Gilded Age of New York, it was a little further downtown, around Herald Square, where the streets were lined with theaters, music halls, and vaudeville amusements. Broadway in the 1890s was said to have a “champagne sparkle.” But the countless theaters listed in the Baedeker–such as the Casino, the Knickerbocker, the Garrick, and the old Metropolitan Opera House–have sadly all been torn down.

So has the old newspaper building that gave Herald Square its name. Theatergoers would have been able to walk past the Herald building, owned by James Gordon Bennett, and later his playboy son, James Gordon Bennett, Jr., and seen the latest news literally hot off the press, the sounds of which would have competed with the 6th Avenue elevated railroad thundering overhead. But today there is only one last trace of the old Herald, in the form of an unusual clock tower made from the salvaged Minerva statue that once adorned the main entrance of the building. It is decorated with owls, Minerva’s totemic bird and a favorite of the Herald’s owner. James Gordon Bennett, Jr. was obsessed with owls, and the roof of the Herald was decorated with owls whose eyes lit up with electric green lights. Several of these owls survive today in Herald Square, their eyes still lighting up a mysterious green, largely unseen by the pleasure seekers below.

This area was also home to New York’s red light district, the Tenderloin. A notorious neighborhood roughly focused west of Broadway between 23rd and 40th Streets, the Tenderloin was full of vice, flagrant prostitution, gambling dens, clip joints, and freak shows, all in operation due to liberal bribes to the Police Department and Tammany Hall. The brothels which lined 39th street, which was known as Soubrette’s Row, were especially sordid. One Baedeker writer reported: “The French girls in these houses resort to unnatural practices and as a result the other girls will not associate or eat with them.”

Baedeker’s advice on venturing here: “Dime museums can scarcely be recommended and visitors should also steer clear of most of the concert saloons.” Today, the area around Herald Square remains just as bustling, but the days of vice and theatrical entertainment have long since disappeared.

Karl Baedeker’s travel books were the grandfather to the Lonely Planet and Rough Guides. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

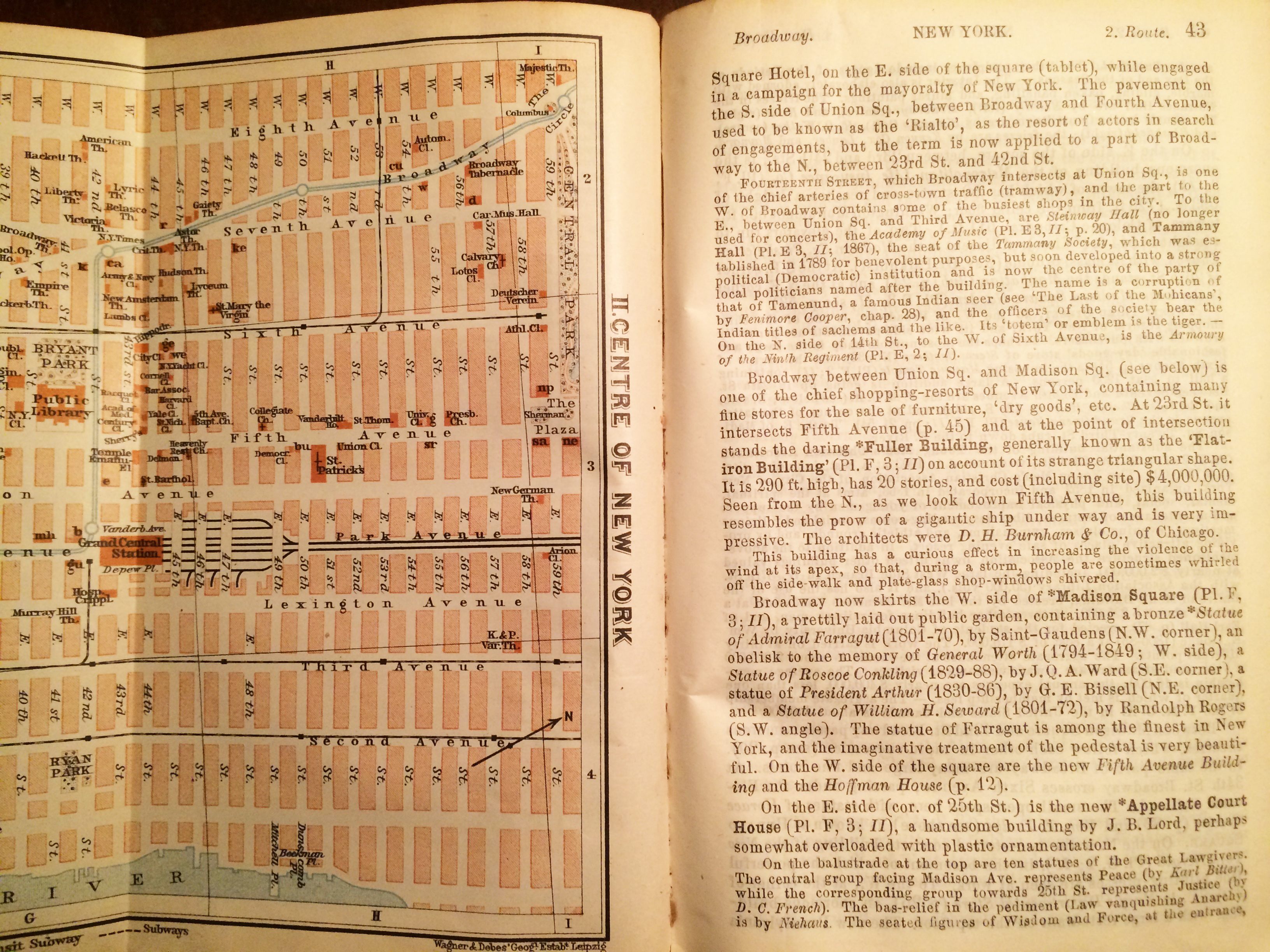

Next morning, sightseeing was the order of the day. Baedeker pioneered the idea of “must-see lists,” and my guide’s list of principal attractions would be familiar to a tourist today: walking down Broadway and visiting Central Park, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Natural History.

Chief on my Baedeker’s must-see list was a visit to Park Row. Located on the southeast side of City Hall, this was once the bustling home of most of New York’s newspapers. According to my guide, New York at this time carried an astonishing 50 dailies and 200 weekly papers. Dubbed Newspaper Row, the location is now more familiar as the place where the vast J&R electronics store used to be. The former home of the Times, Sun and Tribune, among others, now lies mostly silent.

Working up from Newspaper Row, next on the Baedeker must-see list was a visit to Five Points and the Bowery, which the guide said was “full of drinking saloons, dime museums, small theatres and huckster’s stalls, and presents one of the most crowded and characteristic scenes in New York.” On an early Saturday morning in 2015, the Bowery remained full of drinking saloons, but perhaps not quite as salubrious as in 1899.

The mysterious Doyers Street, home to underground tunnels, old Chinese theatres and countless murders giving it the deserved name ‘The Bloody Angle’. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Gentrification has stripped these neighbourhoods of much of their grit, but it is interesting to note that this process was already in place when my guide was written: “The Five Points once bore the reputation of being the most evil district in New York,” said the Baedeker. “It has however of late been wonderfully improved by the … invasion of commerce.”

But there were still seamier delights to be had as I followed the guide to Mott Street and “one of the opium joints” Baedeker recommended going to “in the company of a detective.” Despite my desire to conduct thorough research, the prospect of approaching a police officer and asking him to accompany me into what used to be an opium den didn’t seem particularly wise.

Leaving the denizens of the former Five Points, I headed in the direction of Astor Place, and the “handsome building of the Mercantile Library, completed in 1891.” This was once the site of an opera house, in front of which the “Shakespeare Riots” occurred. My Baedeker had the story: here “in 1849 took place the famous riot between the partizans of the actors Forest and Macready.” The riot originated in a dispute between supporters of two actors, one English and one American, over who could best perform the roles of Hamlet and Macbeth. Loyalties were roughly split between the leisure classes of uptown (favoring England) and the lower classes below Astor Place (favoring the United States), and stemmed from still-lingering resentments over the Revolutionary War. The cause of the riot may seem slightly frivolous, but the outcome was anything but; more than 20 people died. Today the library building is still there but as an apartment house, with a Starbucks on the ground floor.

One of the principal attractions in visiting New York during the Gilded Age was the shopping, then as now. For the gentleman traveler, Baedeker recommended the “large dry goods stores, huge establishments in the style of the Bon Marche in Paris, containing almost everything for a complete outfit.” Of these, some are still thriving today, particularly Macy’s and Lord & Taylor. The grandest store of them all was located on West 23rd Street: the magnificent Stern Brothers. Today this is a vast branch of Home Depot, but the beautifully ornate exterior is relatively unchanged. It still features the elaborately detailed, but largely unnoticed, “S B” above the doorway.

Today a Home Depot, this beautiful building on West 23rd Street was once one of Manhattan’s premier ‘dry goods’ stores, the marvelous Stern Brothers. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Using the detailed map of New York in my Baedeker, I made my way to Fifth Avenue and 29th Street for the next stop on the book’s list: “the odd looking Church of the Transfiguration, popularly known as the Little Church Around the Corner.” This church’s name came from the refusal of the rector of a neighboring church to officiate the funeral of a well-known actor; instead, he referred the requester to “the little church around the corner.”

The Little Church Around the Corner, favored church of actors and playwrights. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Having lived and explored New York for the best part of a decade, it was delightful to have the Baedeker turn up something I’d never heard of before. Stepping inside, I talked with the current vicar at this small, charming Episcopalian church, the Right Reverend Andrew St. John, who explained that during this era, acting was somewhat frowned upon as a profession, which was why the rector of the larger church refused to conduct the funeral service.

Since then, the Little Church Around the Corner has been the favored place of worship for local playwrights and actors. The Baedeker made special mention of the Edwin Booth “memorial window.” Booth, one of the most celebrated actors of his day, was brother to the infamous John Wilkes Booth. The stained glass window in the Little Church showed a full-length Booth pondering an actor’s mask.

Beautiful stained glass of celebrated actor Edwin Booth, presented to the Little Church Around the Corner by members of the Player’s Club. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Consulting the Baedeker about where next to visit, and being informed that “Seventh Avenue calls for no special mention” and “Eighth Avenue is also featureless,” it was time to turn to the 19th century gentleman-of-leisure’s chief pastime: sport.

“To enter into the spirit of American pastimes, an Englishman need only to learn to admire the gait of the trotting horse and to admit the merits of baseball,” said the guide. As the baseball season was over, that meant a visit to the Aqueduct race track in Queens. There I came across the first instance of something being more expensive in 1899 than it is now: entrance to the grandstand cost $2 then, whereas today it is free.

Back in the city, there was only one place for dinner: Delmonico’s. Located downtown at 2 South William Street, the entrance is flanked by columns rescued from Pompeii. Opened in 1837, Delmonico’s was the first American restaurant to allow diners to order from a menu a la carte, to operate a wine list, and where dishes such as Eggs Benedict, Baked Alaska, Lobster a la Newberg and Manhattan Clam Chowder are said to have been invented.

The celebrated Delmonico’s; legend has it the stone pillars were rescued from Pompeii. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

For the evening’s entertainment, the undisputed crown jewel of the Gilded Age of New York society was Madison Square Garden. Located on the northeast corner of Madison Square Park, and designed by Stanford White, who went on to live in a tower on top of the Garden, it was a luxurious complex featuring, according to the Baedeker, an amphitheater seating 15,000 for horse shows, a theater, a concert ball room, and an open air garden on the roof. Perched atop Stanford White’s towering apartment was the golden statue of the goddess Diana, a controversial decoration, since she was depicted fully nude. White himself was murdered in the open air garden in 1905, at the hands of his one-time lover, Evelyn Nesbit’s enraged husband, Harry Thaw.

Unfortunately this pleasure palace was torn down in 1925, so instead I paid a visit to the current incarnation of the Madison Square Garden arena, three quarters of a mile away near Pennsylvania Station. What the 19th-century gentleman would have made of that night’s act—the remaining members of the Grateful Dead, plus John Mayer—is hard to say.

Coming to the end of my travels with the Baedeker, I was struck by how accurate the guidebook still was. It was a testament to both the endurance of the city and the thoroughness of the guide itself. While many theaters, old hotels, saloons, and restaurants have long since disappeared, much of the Gilded Age of New York still remains. The Baedeker even turned up hidden treasures like the Little Church Around the Corner, which I might otherwise have overlooked.

Baedekers fell out of favor with English readers following World War I, and censorship– first by the Nazis, and then during the Cold War–made them all but disappear. They were re-launched in 2007, but Baedeker found themselves far down the pecking order compared to newer guidebook. But the classic editions are greatly prized by collectors for their detailed descriptions of countries and cities from a century ago, including details long since forgotten. If you can get your hands on one, try taking it for a spin; you might find that it still works.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook