The Eccentric Father of Early American Taxidermy Practiced on Ben Franklin’s Cat

Charles Willson Peale befriended the founding fathers and started the first U.S. natural history museum, among other accomplishments.

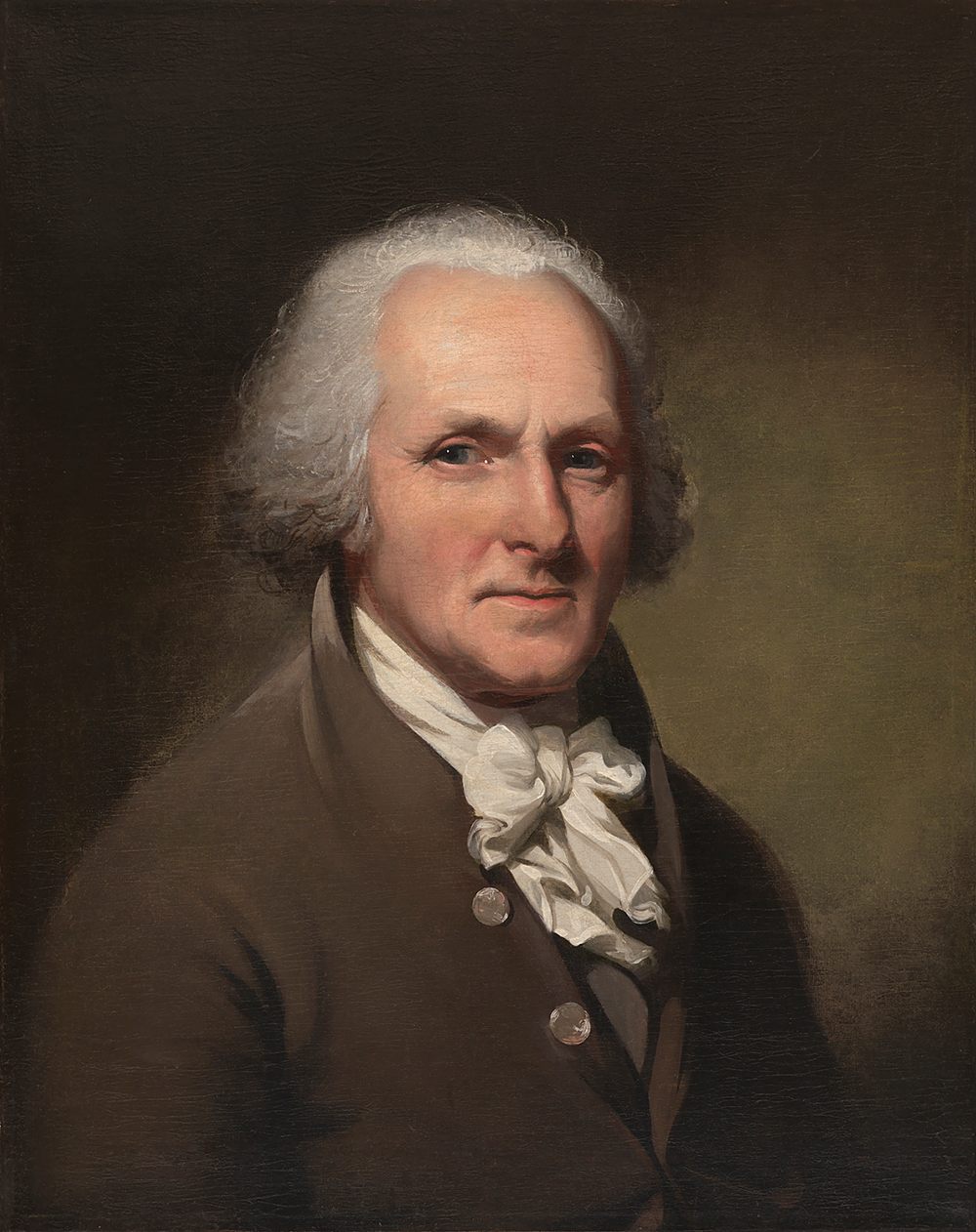

The Artist in His Museum, a self-portrait by Charles Willson Peale. (Photo: Philadelphia Museum of Art/Public Domain)

Birth, death, decomposition, and a return to the earth—the endless cycle of which almost all of us are a part. But a small percentage of creatures attain immortality through the sometimes kitschy, somewhat macabre, art of taxidermy.

Alas, Benjamin Franklin’s angora cat wasn’t one of them.

Charles Willson Peale is usually remembered as the father of American painting, but he was also a pioneer of taxidermy in early America. However, he was still new to the art when he attempted to give his friend’s cat the gift of everlasting “life.” “An attempt was made to preserve it,” Peale writes in his autobiography, which he finished in April 1826, less than a year before his death at age 86. “But for want of knowledge of a proper mode to preserve dead animals, it was lost.” Apparently, Peale’s lack of skill left the door open to opportunistic “vermen,” insects that ate away at the carcass. Peale had yet to learn how to thwart the whims of hungry “dermests and moths (the enemies of most Museums),” he writes. The source documents remain silent on how Dr. Franklin took the news of his pet’s second demise.

But Peale was a quick study and his later refinements came to help scientists and civilians prevent pets and specimens from rotting. This also became central to another item on the long list of this polymath’s accomplishments: Opening the first natural history museum in America.

Exhuming the First American Mastodon, by Charles Willson Peale, 1806. (Photo: Peale Museum/Public Domain)

Peale’s ascension to museum keeper signified the culmination of an eclectic career. He started out as an indentured servant apprenticed to a saddle maker at age 13 in his native Maryland. Peale soon became quite skilled. But ever the ambitious craftsman, he added silversmithing and clock-making.

At age 21, sensing that his life should amount to more than a pile of leather and gears, Peale took up portrait painting and made a stunningly successful leap from artisan to artist (and an accompanying jump up the social ladder) upon moving to America’s then capital city, Philadelphia. There, he associated himself with the gentry he painted and became well acquainted with Franklin, Washington, Jefferson, and the other founding fathers.

Despite his intelligence and many talents, Peale was forever short of cash. With 17 children to support, he constantly sought new opportunities. Some mastodon bones discovered in the mid-1780s presented the mammoth opportunity he’d been searching for when Peale’s brother-in-law offhandedly remarked that people would pay to see them. That simple statement sparked the idea of creating a museum of natural history.

“Peale was a pioneer in terms of thinking about what a museum might be in a democratic republic,” says David Brigham, President and CEO of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA), another institution Peale founded, in 1805, that houses his most iconic painting, The Artist in his Museum. “He’s been thinking about these things from the 1780s forward, and he created two of the most important cultural institutions in the young republic—Peale’s Museum and the PAFA. He really had a tremendous impact,” Brigham says.

An advertisement for “lectures and personifications” at Peale’s Philadelphia Museum. (Photo: Library of Congress/rbpe 15501100)

The Philadelphia Museum, also called Peale’s Museum, which opened in July 1786, presented preserved animals and other natural specimens carefully arranged according to the Linnaean taxonomy alongside portraits of important figures from the American Revolution. Peale intuitively understood that art and science overlap and that a dose of entertainment makes learning more palatable to everyone. Having been compared both to circus showman P.T. Barnum and to Joseph Smithson, the scholarly founder of the Smithsonian Institution, Peale’s dynamic and sometimes domineering personality sits him somewhere between these two extremes.

He writes in his autobiography of using the necessity of moving the collection in 1794 from its original location in his home at Lombard and Third Streets into Philosophical Hall (roughly half a mile away) as a way of creating a buzz. “But to take advantage of public curiosity, he contributed to make a very considerable parade of the articles…. And as Boys generally are fond of parade, he collected all the boys of the neighbourhood, & he began a range of them at the head of which was carried on men’s shoulders the American Buffalo—then followed the Panthers, Tyger Cats and a long string of Animals of smaller size carried by the boys…. It was fine fun for the Boys.”

It must have been quite a show for regular Philadelphians, too, watching a cavalcade of dead animals waltz past, and Brigham says that in providing a spectacle as a way for potential museums-goers to engage with science and the natural world, Peale “was synthesizing popular and more scholarly ways.”

“To call him either a Smithson or a Barnum is not right; he had the idea that those two things are very comfortable together,” Brigham says.

Peale charged 25 cents for a single visit (about $6 in today’s money) and established the concept of museum membership by offering an annual subscription that allowed unlimited visits and entry to special events and lectures.

Charles Willson Peale self-portrait, c. 1791. (Photo: Courtesy National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

Through his museum, Peale’s mission became to decipher the natural order underpinning disparate intellectual pursuits while educating anyone who could afford the entry fee, says David C. Ward, senior historian at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.

Ward describes the period between 1785 and 1805, when Peale taught himself the museum business, as a time of intense “ferment, during which everything is up in the air. They’re creating institutions, the constitution, even the street grid in Philadelphia and ordering their life experience. It’s kind of an incredible American story,” he says. Peale was on the front lines of this exciting time. “He creates this museum out of his head and creates ‘A World in Miniature.’ The specimens became analog to the human world, with man surrounding the natural world and controlling and understanding it,” Ward says.

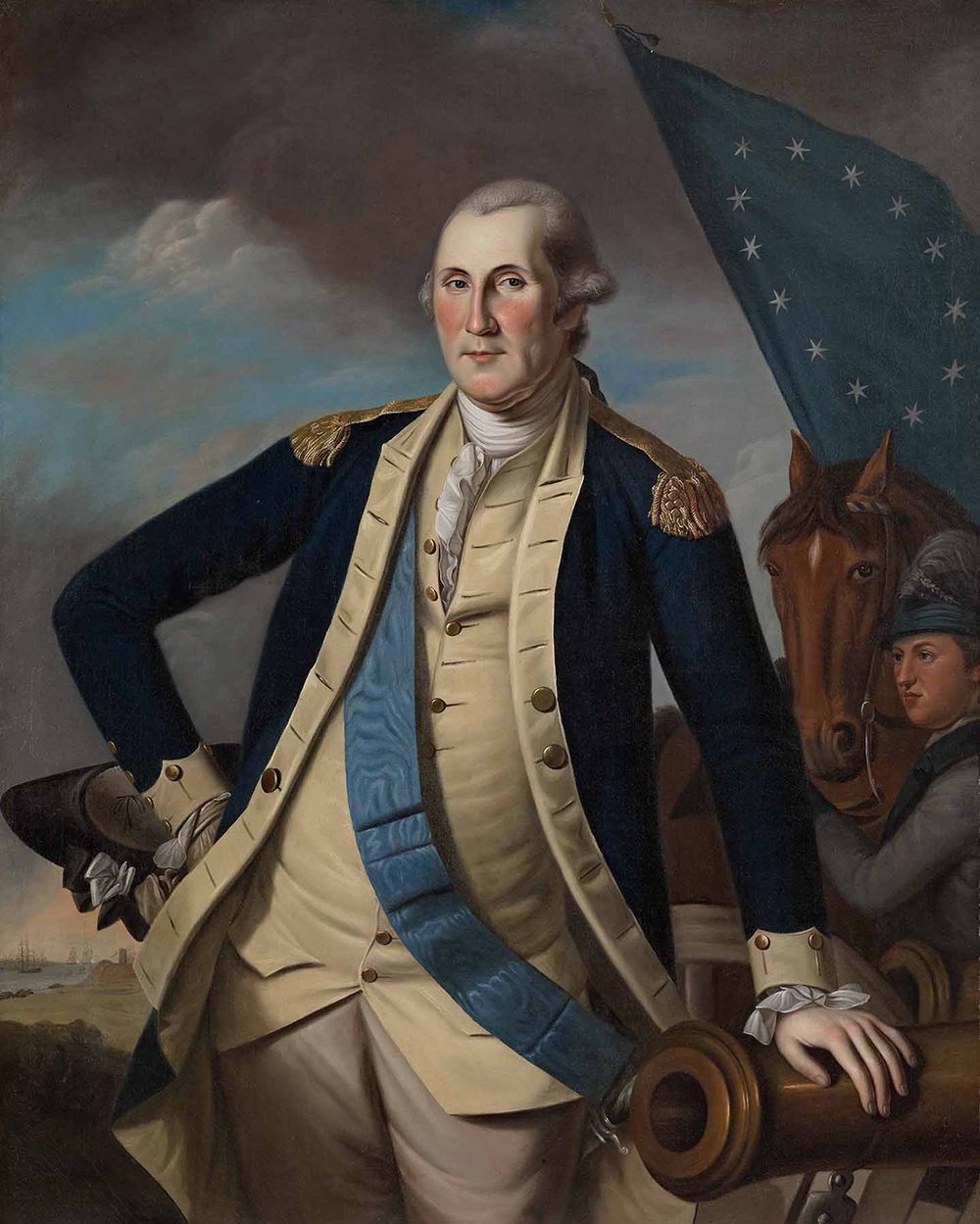

And that heightened understanding of our world through these specimens continues today. Ornithologist Scott Edwards, curator of ornithology at the Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ) at Harvard University, says older specimens can serve “as a snapshot, or time capsule, of the environment in a specific time and place.” Using technology far beyond even Peale’s fertile imagination, Edwards can analyze cells from old specimens, such as two golden pheasants donated by George Washington and preserved by Peale in 1787 that are still on display at the MCZ to sequence DNA, measure levels of environmental chemical exposure, and answer a host of other questions about how species change over time.

Peale’s painting of George Washington, c. 1780-82. (Photo: Courtesy Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art)

And while efforts are underway to digitize the entirety of the MCZ’s collections to make them accessible to anyone, anywhere—an endeavor Edwards thinks “would impress our pre-digital ancestor, Peale”—there’s simply no way to replace the experience of seeing preserved specimens in person. “If people still appreciate the difference between the image and actual specimen, museums have a long future,” Edwards says.

As for his contribution to taxidermy, Peale’s main innovation was arsenic, a technique he likely learned about and improved upon based on German naturalist Johann Reinhold Forster’s “Catalog of the Animals of North America,” published in London in 1771. Peale used the poison in preserving Washington’s pheasants and nearly all his other mounts, despite experiencing some adverse health effects. The caustic and highly toxic chemical proved a harsh solution to his preservation problem but is responsible for the birds remaining intact today. According to Jeremiah Trimble, collection manager at the MCZ, the pheasants “are a bit faded” but otherwise in excellent condition. “They still have the original labels from the Peale Museum,” he says.

With his formula finally sorted (his notes reveal a lengthy and no doubt foul-smelling process), Peale was able to stock his museum with all manner of fauna from near and far. No mere curiosity cabinet, Peale’s Museum was a decidedly scientific institution that serves as the mould from which most modern museums are still cast today.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook