The Elaborate Wig-Snatching Schemes of the 18th Century

Thieves employed monkeys to rob the wealthy of their coiffures.

In 18th-century England, it was best to be wary of any hands that reached too close to your hair. They could belong to a wig snatcher.

The 1776 engraving above depicts one of the carefully plotted hair heists. A wealthy woman walks along a high orchard wall in the latest fashion—an enormous headdress wig trimmed with lavish lace and ribbons. Suddenly, the intricately combed and curled set of hair is lifted from her head by a monkey perched on the wall, revealing her bare head.

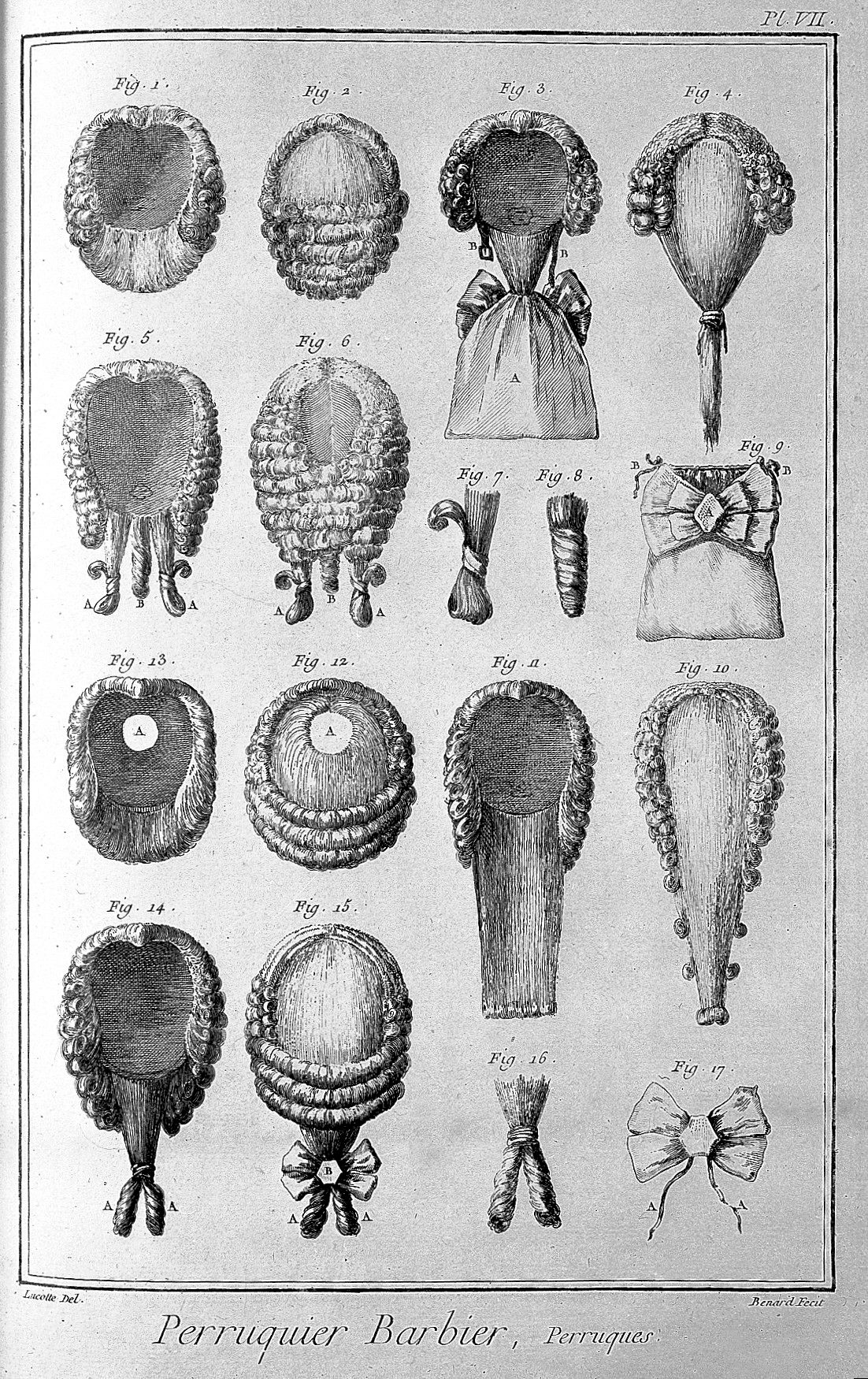

Socialites had to be extra cautious of wig snatchers. Throughout England and Europe, finely powdered perukes, also called periwigs, were in vogue among royal courts and the upper class. The more ornate and towering your wig, the higher your social standing. The expensive and easily removable headpieces led to a series of wig thefts: surprisingly elaborate and creative robberies involving animals, long poles, and young boys hauled on the shoulders of impostor butchers.

One of the most successful wig-stealing schemes involved concealing young boys in baskets and under blankets, according to William Andrews, author of the 1904 book At the Sign of the Barber’s Pole. In an episode in England, a boy rode in a butcher’s tray carried on the shoulder of a tall man. As the pair walked passed a victim, the boy twisted the periwig off the head and the man would take off in the opposite direction, leaving the confused owner clutching at his or her now bald head.

The same tactic would be used with boys hidden in baskets held by wig stealers, writes Robert Norman in The Woman Who Lost Her Skin (and Other Dermatological Tales).

In addition to using monkeys, wig thieves also employed dogs. One boy would harass a finely dressed, bewigged gentleman as another seized the hair and toss it to a dog, explains Margaret Visser in The Way We Are: What Everyday Objects and Conventions Tell Us About Ourselves. All three would split down different alleys and later meet up to celebrate their plunder. Meanwhile, the bald victim would often be more concerned about covering his head and pride than running after the thieves, Visser writes.

The social elite in both France and England also had to beware of the highwaymen who roamed country roads. Thieves known as “chiving lays” would lurk behind hackney coaches, which were forced to roll slowly down narrow and poorly paved streets, and slice the back of the carriage to snatch a wig from the passenger’s head, explains Geri Walton. Highwaymen riding on horses would also target coaches, stealing wigs and quickly riding off.

In one heist, highwayman John Everett had an interesting means to obtain a better wig—he forced a man to trade. Fiona McDonald notes in Gentlemen Rogues and Wicked Ladies:

“Everett fancied a bob wig that sat atop the head of a Quaker seated in a coach with a number of other passengers. Everett pulled it off the man’s head and swapped it with his own second-hand tie wig (which he had bought, not stolen). The tie wig made the man look like a comical devil and the rest of the coach party burst out laughing. The robbery ended with all parties going their separate ways without any hard feelings (except perhaps from the Quaker).”

Everett was arrested shortly after this robbery, and was detained in prison for three years. However, many wig thieves often got away without punishment. For example, Christopher Matthews was accused of stealing a valuable wig in 1716, reports indicating that there was little doubt he had committed the crime. But the chief prosecution witness strangely did not come to his trial, and the jury were “oblig’d to acquit him,” explains Gregory Durston in Whores and Highwaymen: Crime and Justice in the Eighteenth-Century Metropolis. It’s implied that Matthews may have been involved in witness’s attendance.

In England, only 4.3 percent of all types of theft cases were brought to the Old Bailey during the 18th century, and 70 percent of those accused were found not guilty.

Precautionary measures were taken to prevent wig theft, writes Andrews. According to The Wigmaker in Eighteenth-Century Williamsburg, colonial wigmakers sometimes added a drawstring or small strap and buckle at the back of the wig so a wearer can fasten the wig tighter. However, it’s unclear whether or not these features were developed as a result of wig theft.

As they grew out of style and taxes were imposed, large periwigs lost their value and the inventive plots to steal wigs became part of the past. Still, the fear of wig conspirators was potent, as 18th-century English poet John Gay once wrote:

Nor is the flaxen wig with safety worn:

High on the shoulders in a basket borne

Lurks the sly boy, whose hand, to rapine bred,

Plucks off the curling honours of thy head.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook