The Explosive Truth Behind the Movie Theater Projection Room

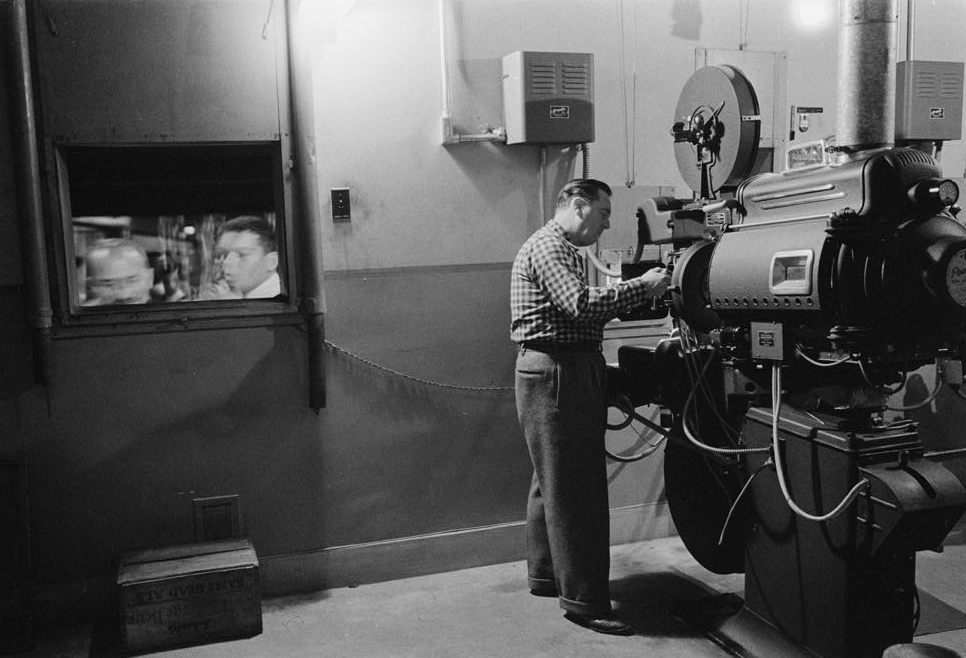

A movie projectionist at a theater. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Nitrate motion picture film, or celluloid, was the original medium for Citizen Kane, Gone With The Wind, The Man Who Knew Too Much, Casablanca, and The Wizard of Oz—not to mention thousands of other movies screened before 1951, including practically every silent film ever made.

Celluloid is also extremely dangerous. It is essentially a solid form of nitroglycerin dragged across superhot carbon rods at extremely high speed. If celluloid combusts, which it can do at “car parked in the sun” temperatures, the fire generates its own oxygen, creating a flame which cannot be extinguished. It can burn underwater. It can burn beneath a fire blanket. It burns until the celluloid is gone, and any attempt to smother it creates clouds of poison gas.

Old celluloid film rolls. (Photo: Marcel Oosterwijk/flickr)

During the postproduction process of Akira Kurosawa’s 1950 film Rashomon, editors had to contend with their film bursting into flames before their eyes. And it didn’t just happen once. Teruyo Nogami describes one such incident during the second fire of the postproduction process, which happened just a day after the first one:

“Suddenly the picture on the screen froze; evidently the film was stuck in the projector. The next thing we knew, the center of the projected film frame began to turn black, a hole opened in it, and then it was in flames. All of this showed on the projection screen. “Another fire!” we shouted, and scrambled outside. Smoke billowed from the projection room.

As before, everyone scurried around, carrying bits of the film to safety. Benitani and some others, feeling like old pros, formed a bucket brigade to throw water inside the burning room, but this turned out to be a mistake: the nitrate film stock then released a poisonous gas, filling the room instantly with clouds of noxious smoke. Otani and Benitani both had tears streaming from their eyes and saliva drooling from their mouths, and suddenly they fell down, unconscious.”

Almost every studio archive suffered a vault fire that wiped out its holdings. A 1922 electrical fire burned Universal’s film storage unit. A hot New Jersey summer was enough to immolate every movie made by Fox before 1937; although seven fire companies arrived on the scene, there was nothing they could do as the flames ate through 48 vaults of film. In 1965, the storage sheds at MGM exploded. All in all, there have been at least 15 major archive fires. Those are just the accidental ones; old film reels were often intentionally burned to recover their silver, and the Los Angeles fire department ran voluntary film stock collection drives in the 1930s to reduce the risk of neighborhood conflagrations.

Decayed nitrate film. (Photo: Hansmuller/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 4.0)

Celluloid’s combustibility is the reason projection rooms exist; it would have been cheaper and easier to place the projector in the middle of the auditorium. But in case of fire, the projection booth could close down like a tomb. Each glass window was crowned with a fireproof shutter, held in place by a wax seal; any dangerous blaze would melt the wax, and the shutter would slam down—even if the projectionist was unconscious, or worse. (A 1936 issue of International Projectionist estimated one American projectionist died, on average, every 18 days.) But fire shutters were a last resort; more often, a fire was contained by the projector itself, which isolated almost every frame of film from the surrounding air. Big enough projectors were water-cooled, and fancier booths had not only fireproof cabinets, but totally separate film storage rooms on the other end of a cement corridor.

As for the projectionists themselves, they were highly trained. In Australia, they held degrees in projection and the equivalent of an electrician’s certificate, considered necessary because of the high voltage projectors required. In the United States, a strong union admitted few new members.

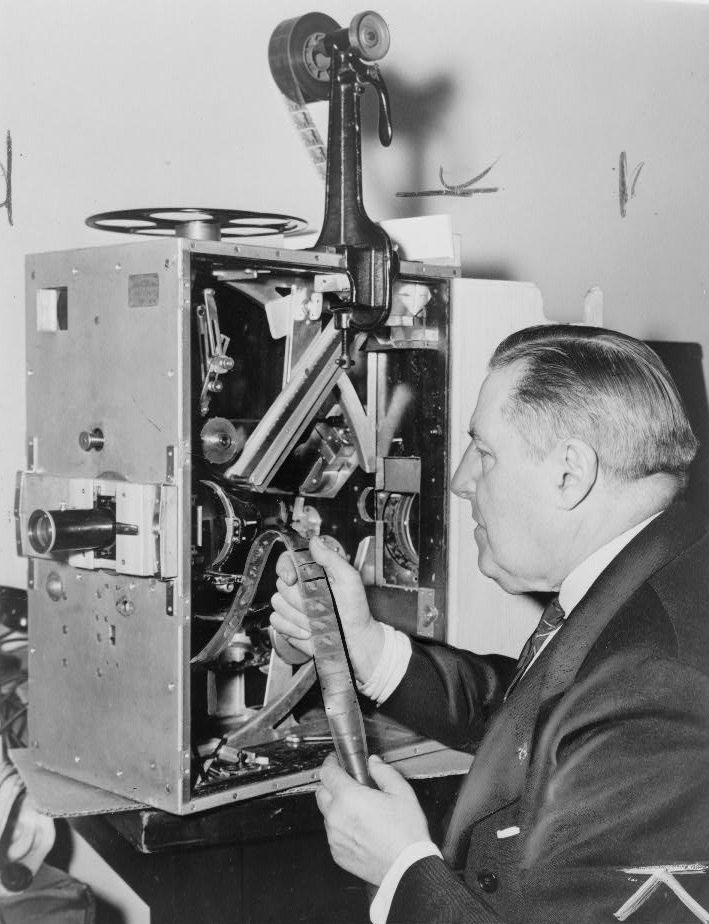

Cinematographer Billy Bitzer seated at a movie projector. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Why, you might ask, use celluloid at all, particularly since Kodak started manufacturing less flammable acetate “safety film” in 1908? Acetate was the only stock available to amateurs, and the pros used it in situations where nitrate couldn’t be safely isolated—like on board airplanes. It was especially popular with pornographers and British directors of politically controversial movies, thanks to a legal loophole in celluloid-focused censorship laws. And acetate was embraced by the Nazis toward the end of World War II, on the grounds that they were being bombed and would rather not be holding nitrocellulose firebombs-in-waiting when it happened.

Everybody else stuck to celluloid until Kodak discontinued it in 1951. For all its faults, celluloid is a good plastic. It’s strong; it doesn’t tear easily. It’s also pliable enough to be tightly spooled and unwound many times without cracking. And according to a staunch old-guard of film lovers, celluloid just looks better than later film stocks. The blacks are bulletproof. The whites are more luminously alive. Unlike videocassettes from the 1980s, nitrate prints from the 1940s still project a sharp image. At least, they do if they haven’t combusted.

Fritz Lang, the director of Metropolis, during filming Woman in the Moon, 1929. (Photo: Bundesarchiv Bild/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0 DE)

Only 30 percent of the films made before 1930 have survived—just 14 percent in their original format. Some are missing one or more of their many reels, resulting in disjointed viewing experiences. Metropolis was missing about a quarter of its runtime until three forgotten reels were found in Buenos Aires in 2008; now it’s only short a few minutes. Vampyr, an early sound/silent hybrid, has been cobbled together from German, French, and English language versions, rendering the protagonists freshly multilingual.

Nitrate film is still being destroyed today, on purpose. Germany somewhat notoriously treats the film stock analogously to land mines—it’s governed by the Explosives Act, and the remaining inventory is being systematically scanned and dissolved. Whether that’s for the best is hotly debated among archivists. Collector and projectionist Dennis Nyback contends that Hollywood directors of the silent era and up into the ’50s lit their sets based on “nitrate film being the conduit of their vision.” When these films are converted to newer formats, he says, their look changes: “You might be knocked down by the visual beauty by a Hitchcock, Ford, Hawks, Borzage, Murnau, or other old Hollywood film you see now, but you aren’t seeing the film as the director intended it, or as the audiences first saw it when it came out.”

For the modern viewer, there are only a handful of remaining opportunities to see big screen celluloid—or even to be in the same room as a nitrate print. The most reliable and unquestionably legal is the Eastman Museum’s Nitrate Picture Show at the Dryden Theatre in Rochester, New York; the 2016 festival runs from April 29 through May 1, and its programming slate is a secret. Free with a ticket is the unalienable right to act snotty about digital cinema package conversions, and to swear that film is not dead: It’s on fire.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook