The First Hollywood Film to Imagine a Fictional President Was Some Weird Propaganda

Funded, incidentally, by William Randolph Hearst.

A still from Gabriel Over the White House. (Photo: David Inman/YouTube)

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Over the years, the White House has provided ample fodder for films and TV shows of all kinds—whether ass-kicking alien flicks or competing attempts to imagine what it’d be like to be the daughter of the president.

But in the early 1930s there weren’t any movies or television shows about fictional presidents at all.

The pre-talkie era didn’t generate a single film that imagined the potential of a leader who looked nothing like the one in office at the time. (Maybe people really liked Herbert Hoover? Oh … yeah. Nevermind.)

The Great Depression, however, created the perfect opportunity for the first such film—and, seen today, that film, 1933’s Gabriel Over the White House, is a bizarre relic of a previous era, even if it is also capable of offering some trenchant commentary on our current one.

Gabriel was funded by William Randolph Hearst, a known fascist sympathizer, and creatively influenced by Franklin Delano Roosevelt (who was reportedly a fan of the movie). It is is a radical propaganda film, offering a vision of the future that is by turns idealistic and disturbing.

The movie poster. (Photo: Courtesy Warner Bros)

Based on a book of the same name, Hearst, a publishing magnate who was said to have inspired the plot of Citizen Kane, played a significant role in formulating the dialogue, author Louis Pizzitola notes in his 2002 book Hearst Over Hollywood:

It is easy to see why Hearst was attracted to the domestic and international themes in the novel of Gabriel Over the White House. Hearst was not only able to translate these themes into the action of the film, he wrote whole narrative passages and lengthy dialogue sequences to approximate more closely his own views on fighting crime, invigorating the economy, and disarming the nations of the world. Despite Hearst’s extensive input, however, he was not satisfied with the end product, which had gone through several editing stages.

The film imagines its leader, President Judson Hammond, as a powerful, noble public official. Played by Walter Huston, who previously portrayed Abraham Lincoln on screen, Hammond first starts out as a corrupt do-nothing along the lines of Warren G. Harding.

But after a car wreck and a coma, Hammond is imbued with the spirit of the archangel Gabriel and miraculously recovers, becoming an FDR-style leader in the process, quickly introducing a series of social welfare programs. (Done, it should be said, before FDR himself had the chance to do the same in real life.)

But he doesn’t stop there. When members of his cabinet hold a secret meeting to undermine him, he forces all of them to resign. When Congress won’t abide by his plans, he convinces them to vote to disperse, effectively making him a dictator.

And then comes the drive-by shooting, after Hammond, in an effort to end prohibition, nationalizes the sale of alcohol, angering a stand-in for Al Capone, who retaliates as only a gangster would. That attack prompts Hammond to launch a brown shirt-style police force, blow up an illegal distillery, arrest the gangsters, put them on display in a show trial, and then execute them by firing squad.

In the final minutes, Hammond convinces every world leader that the U.S. military is too powerful to stop, urging them to agree to world peace on Hammond’s own draconian terms. Not long after the world agrees, Hammond dies, eulogized as “one of the greatest men who ever lived.”

It might take a disturbing amount of authoritarianism, the movie seems to be saying, but, yes, America can be made great again.

We’ve dealt with a lot of weird portrayals of the White House over the years. Independence Day—in which aliens destroy the White House with a single laser—had Will Smith punching an alien and Jeff Goldblum taking down an the mothership with a Powerbook 5300. There’s also an entire film, played for laughs, that imagines “Deep Throat” as two 15-year-old girls.

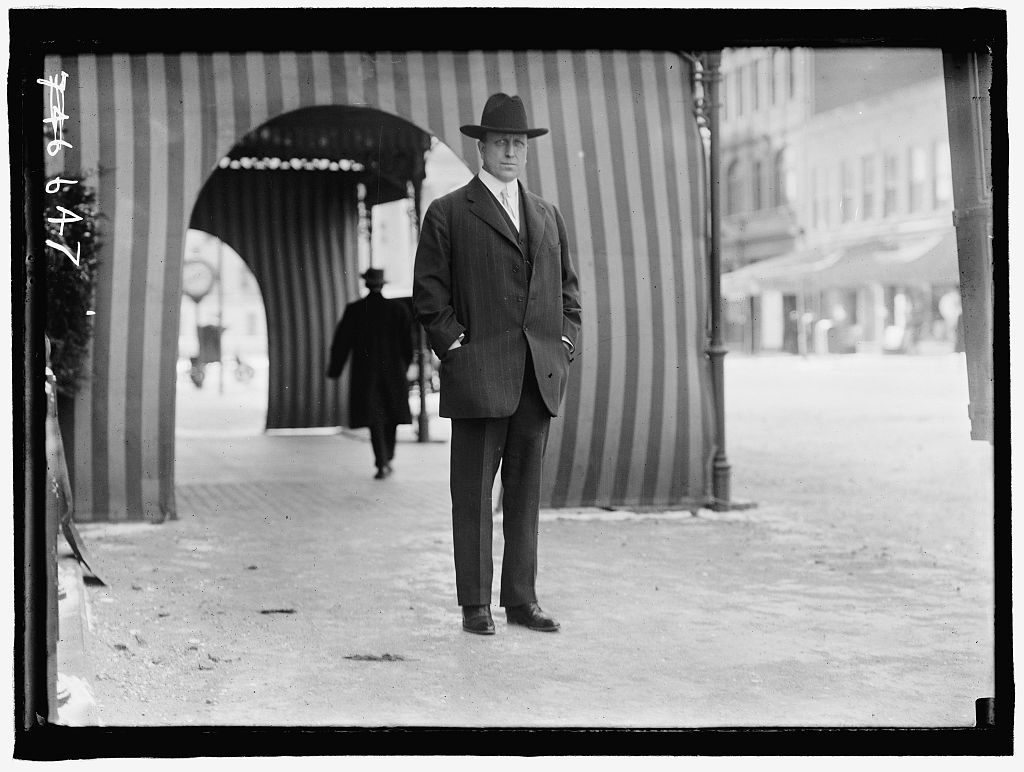

William Randolph Hearst, who bankrolled the film. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-hec-00535)

Still, Gabriel Over the White House, which was funded by Hearst at the nadir of the Great Depression, stands out, in part because of it’s seeming quest to convince viewers that fascism was a noble cause. Great timing, in some ways, since Hitler had just completed his rise to power around the time of the film’s release. (The film was supposedly even more extreme before censors got a hold of it.)

But it was enough of a success that it directly inspired another film, 1934’s The President Vanishes, which came from similar roots—based on a book by an anonymous author, offering a thinly allegorical tale to critique the political climate—and one of Gabriel’s producers, Walter Wanger.

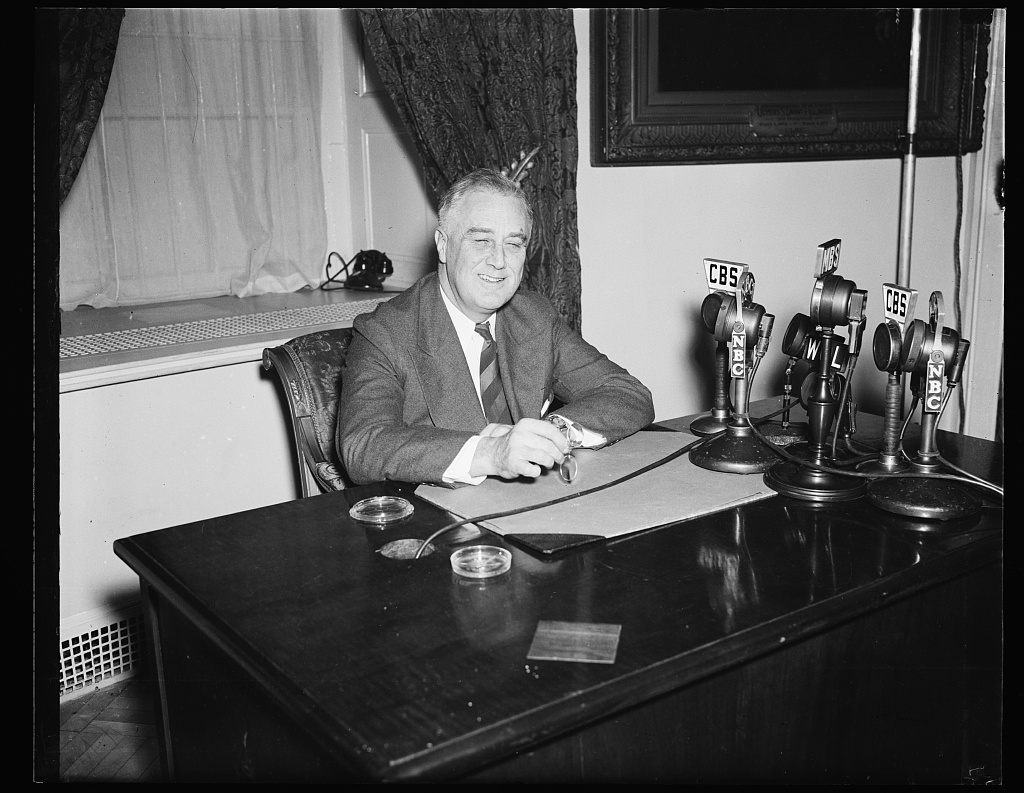

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who was reportedly an influence on - and a fan of - the film. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-hec-47384)

The William A. Weldman-directed film differed in an important way, however: it was a critique of fascism, rather than a celebration of it. Its president, a peacenik named Stanley Craig (played by Arthur Byron), appeared to be kidnapped by a group of brownshirts. He wasn’t—he faked his own disappearance—but it helped him make his case that war is bad and that the U.S. shouldn’t enter whatever mess was happening in Europe. (Hearst, incidentally, wasn’t involved this time.)

“Unlike ‘Gabriel Over the White House,’ which was the naïve mouthpiece for the schoolboy nationalism of a powerful publisher, ‘The President Vanishes’ deserves the attention of sober and intelligent citizens,” wrote New York Times critic Andre Sennwald at the time.

Each film, though, presaged a long tradition of movies starring fictional American presidents, even if political critiques in modern times tend to be more subtle and more cynical, or even played totally straight.

But Gabriel and The President Vanishes were similar to the movies that came after in that all of them seemed to understand the powerful role the medium could play. The first two were clumsy, and maybe even dangerous, but they should at least be credited for attempting to raise political questions over America’s future, something which, in our current political climate, we’re sorely needing.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook