The Government-Funded Tourist Guide Written by Poets and Pulitzer Winners

“A guide to the golden state”: the Federal Writers Project California guide. (Photo: Library of Congress)

In 1975 the TV show The Waltons, a fixture of the 1970s CBS Thursday night lineup, aired an episode called “The Boondoggle.” The episode was mostly about John-Boy wanting to be a writer–they were all, pretty much, about John-Boy wanting to be a writer–but it centered on a government-employed journalist coming to Virginia to do research for the Federal Writers Project’s American Guide Series. The episode was called “The Boondoggle” because Grandma Walton was dead-set against putting writers on the government’s payroll. Writers! Of all people!

But the Guide was real. From 1935 to 1943 the Federal Works Project, under the umbrella of the Works Project Administration, employed over 6,500 writers and editors, artists and photographers, cartographers and researchers, all working towards one grand goal: to take down a full account of the country, state by state, city by city, and deliver it to ourselves. Like Grandma Walton, a lot of people at the time thought the American Guide Series, the FWP, the WPA, and Franklin Roosevelt’s “New Deal” itself were boondoggles. But the project kept thousands employed, including many writers who are household names today.

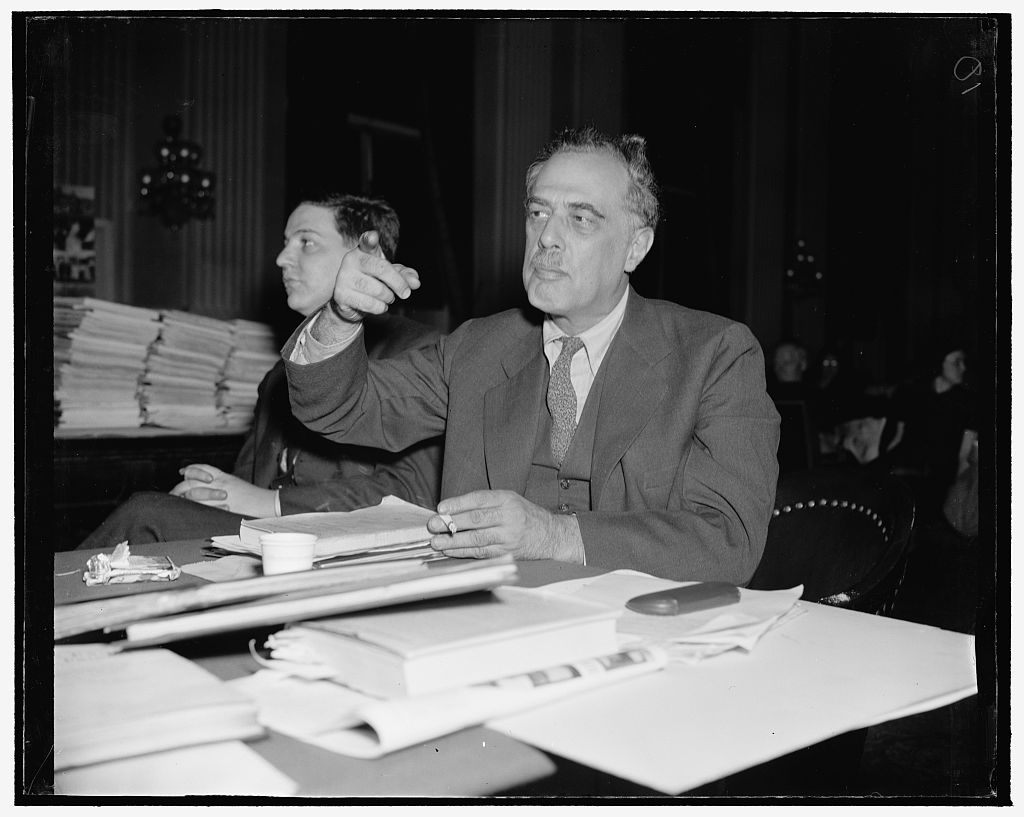

Henry G. Alsberg, Director of the Federal Writers’ Project, in 1938. (Photo: Library of Congress)

The brainchild of an activist and government employee* named Henry Alsberg, the FWP was established in the 1930s as a way to expand employment through government means, beyond the manual labor that was needed for the WPA’s public works programs and building projects. Alsberg’s challenge wasn’t easy: how could the WPA help several thousand workers who were not manual laborers per se? The WPA was not an entitlement program, and Alsberg wanted to have workers produce something–to give them actual work along with an actual paycheck.

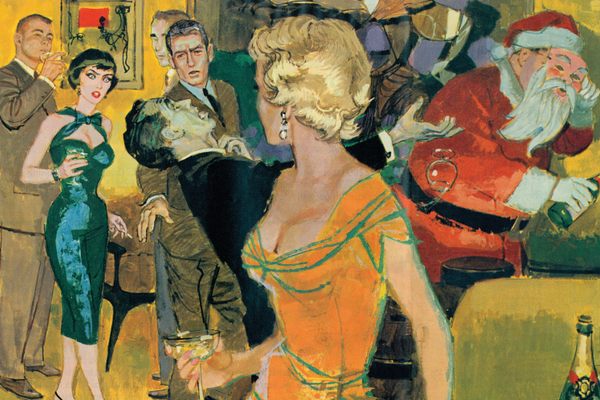

The answer, as the story goes, came at a Washington cocktail party: Katherine Kellock*, a writer employed by the WPA, shouted over the din of the party: “The thing you have to do for writers is to put them to work writing Baedekers.” She meant Baedeker’s United States, the last major U.S. travel guide, which had stopped publishing in 1909 and was both out of print and out-of-date. Luckily Kellock’s advice fell on just the right set of ears: the ones belonging to WPA administrator Arthur Goldsmith.

Goldsmith dropped the hint to Alsberg, who took it as a chance to employ both professional or published writers in need of work, and a much larger group of workers. In his words, Alsberg wanted to employ “near writers… occasional writers… young college men and women who want to write, probably can write, but lack the opportunity.” The American Guide Series was to be that opportunity.

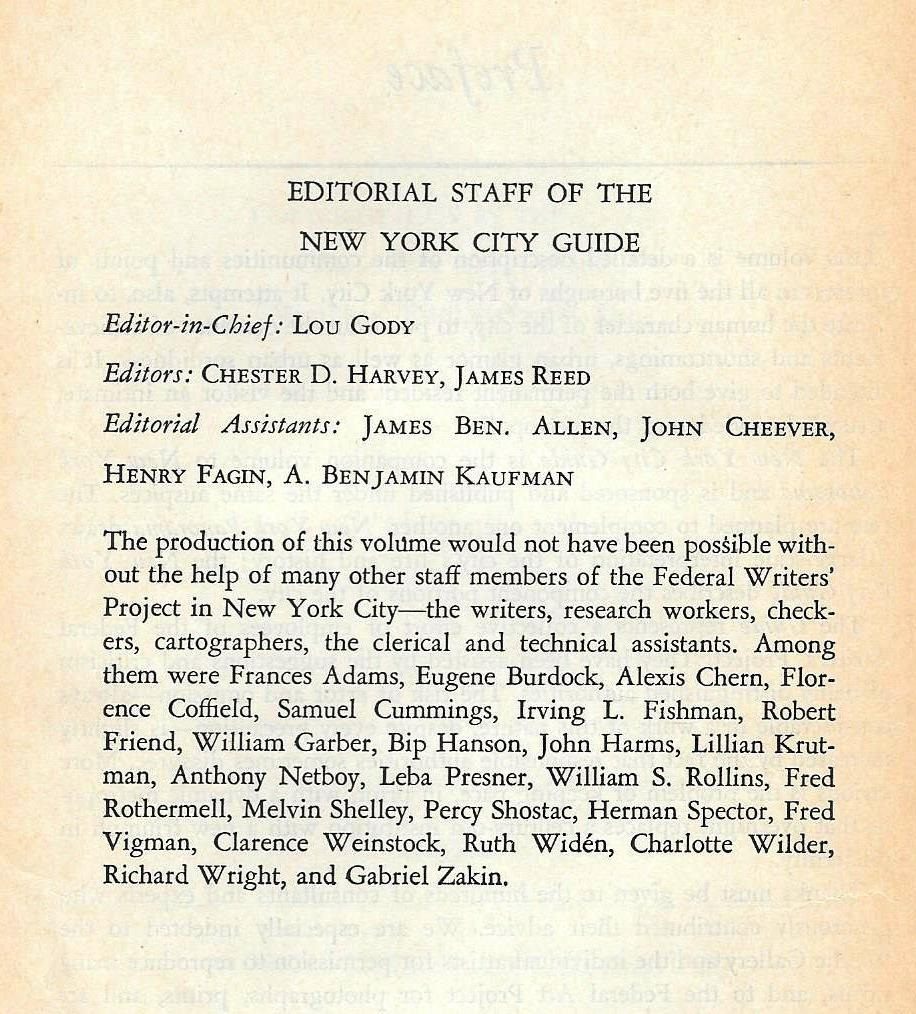

Credits page from New York City Guide. (Photo: Courtesy Anne Reddington)

Over the course of eight years, the FWP hired unknown, well-known, and soon to be well-known writers alike for the series, pairing them with government-paid photographers, artists, and cartographers. Collectively they managed to publish guidebooks for each of the 48 states (Alaska and Hawaii having not yet entered the union), several city and regional guides, and hundreds of pamphlets, maps and guided tours. It’s hard to imagine the difficulty of the undertaking, especially since the project flourished during the later years of the Depression and the first years of the United States’ involvement in World War II. But the sheer amount of information, let alone the breadth and elegance of much of the writing, art and map work, represented the small army of men and women who benefitted from the Federal Writers Project.

There are almost no credited names or bylines in the volumes themselves, but mixed in among the thousands of anonymous and amateur writers were names that went on to have celebrated careers. Ralph Ellison, Saul Bellow, Richard Wright, Studs Terkel, Eudora Welty, and a young assistant editor of the New York City Guide named John Cheever, all contributed to the project.

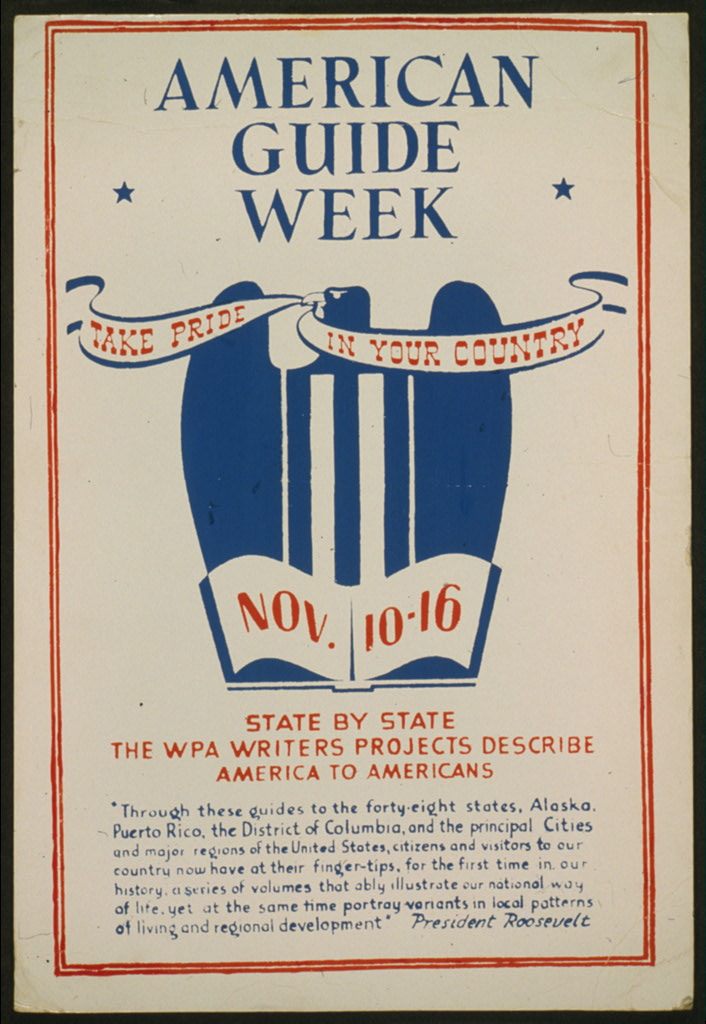

American guide week poster. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Many others, less universally familiar to us now, went on to earn Pulitzer Prizes (like poets Mark Van Doren and Conrad Aiken) and National Book Awards (like Nelson Algren, author of Man with the Golden Arm). Still others came to the project with celebrated writing credentials earned during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and early 1930s, such as Zora Neale Hurston, Arna Bontemps, and Claude McKay, to name three.

For a week in November of 1941, less than a month before the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt asked Americans to celebrate the Federal Writers Project and the American Guide Series. The “American Guide Week” was intended to embrace the ideals of the thousands of writers, artists, researchers and field agents who had come together in order to “describe America to Americans.” That’s the purpose they still serve. In the end, you can’t call the American Guide Series a boondoggle–sorry, Grandma Walton. Today, the volumes aren’t only valuable as history, geography, and first-person travel chronicles; they are also collector’s items, telling us the story of our country and its past.

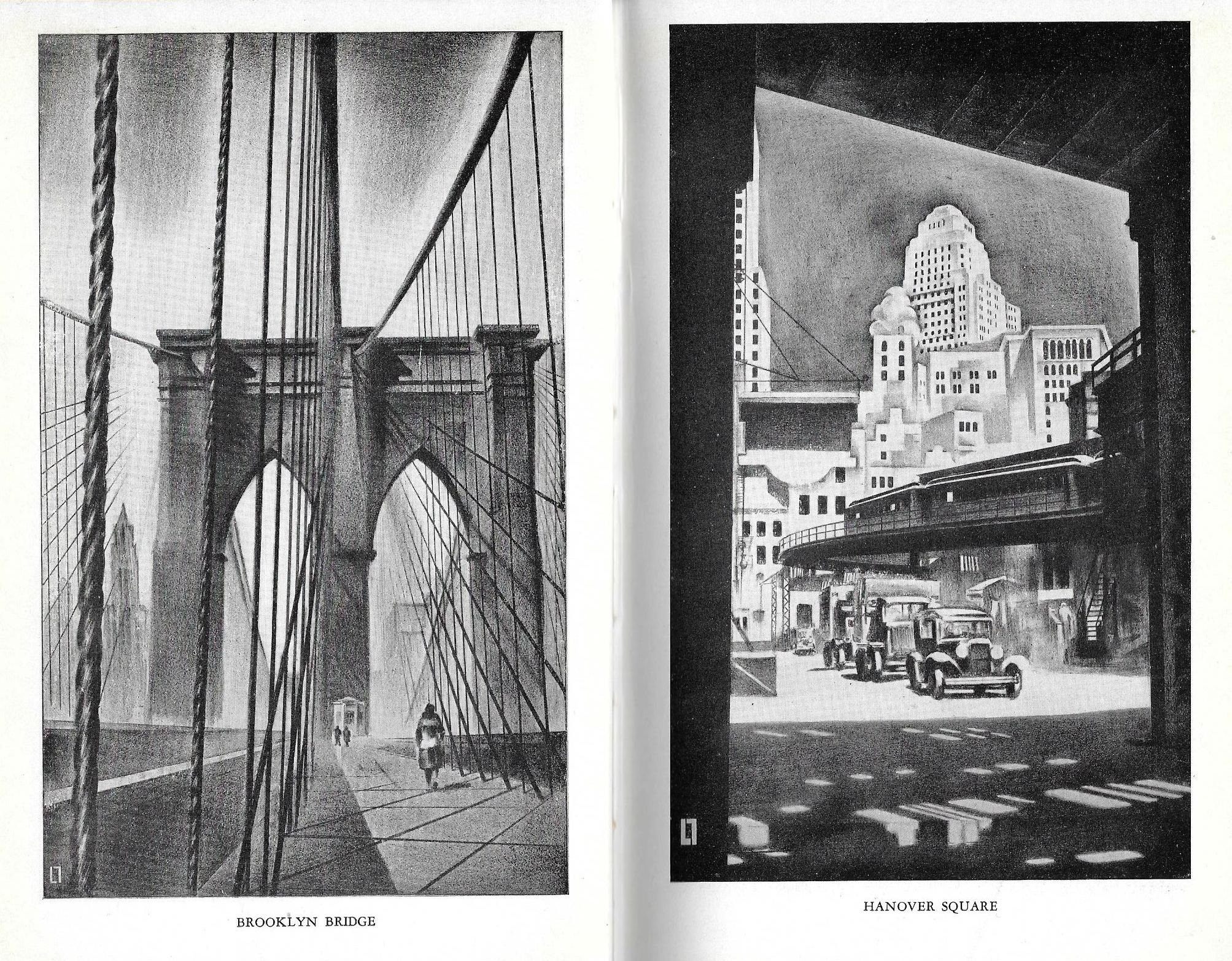

Illustrations from the New York volume. (Photo: Courtesy Anne Reddington)

Many of the descriptions of cities and states are still recognizable almost 75 years later, as in the following excerpts:

It would be a brave man who would sit down, alone or with company, and attempt a portrait of this State.... At best it can hope to provide a few thumbnail sketches, some directions to help the visitor… Looked back upon, it is an age of almost paradoxical contrast, with its conservatism politically and socially, and the radical changes preparing in its factories and workshops, a strange mixture of the past and future working together in a harmonious present, which seemed likely to prolong itself indefinitely… Connecticut, though nearly New York, is really New England.

Galveston, Texas… Seen from the wharves, the harbor, protected by artificial moles, is alive with traffic from a hundred ports; grimy tramp steamers, sluggish, wallowing oil tankers, trim passenger ships crowd the docks; bustling, self-important tugs nose along the larger vessels, thrusting a fruit ship out to sea, edging a steamer gingerly to dock.

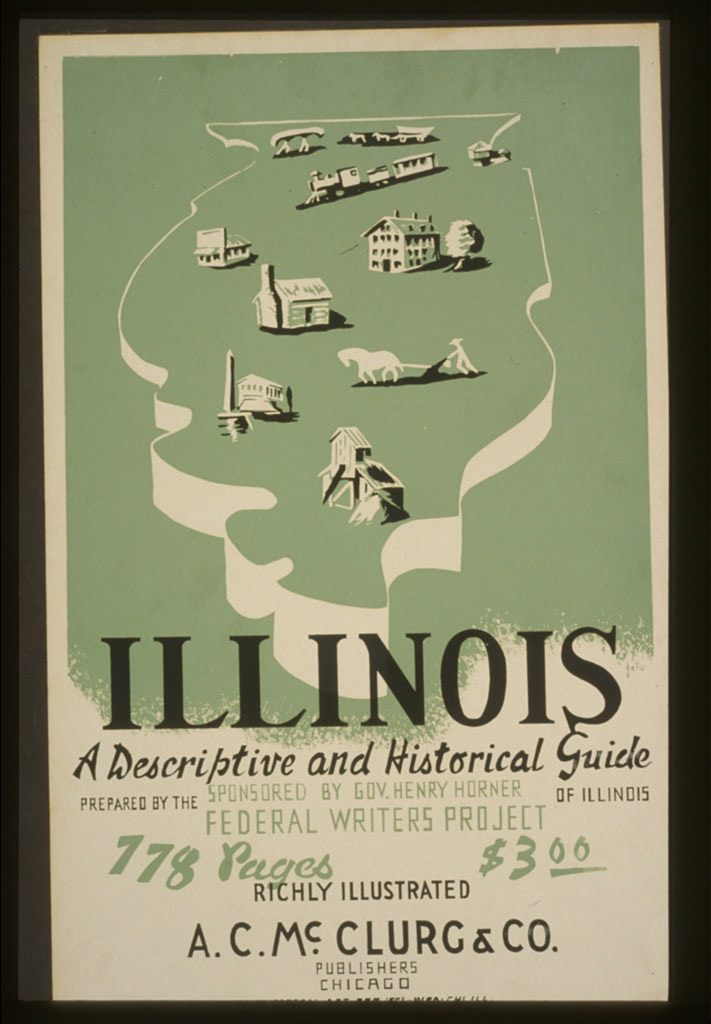

The Illinois volume. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Gargantuan alike in size and rate of growth, the New World’s second largest metropolis, the seventh largest on the globe–“Stormy, husky, brawling, City of the Big Shoulders”–it lies at the point where the long finger of Lake Michigan pushes deep into the continent through the North woods and touches the fertile open prairie, the granary and stock farm of the Nation. Of that contact Chicago was born…

It is this huge army of Federal employees – drawn from every part of the country and organized in scores of separate units, but deriving its livelihood from a common source and therefore held together by a common bond – which chiefly affects the city’s routine life, its economic life in particular…. There are retired officials of every sort – ex-Senators and ex-Representatives; Army and Navy men, to whom Washington is the only fixed point in an unstable universe… There are journalists and press correspondents, probably the largest group of its kind in the world, who mirror and echo Washington life for the Nation.

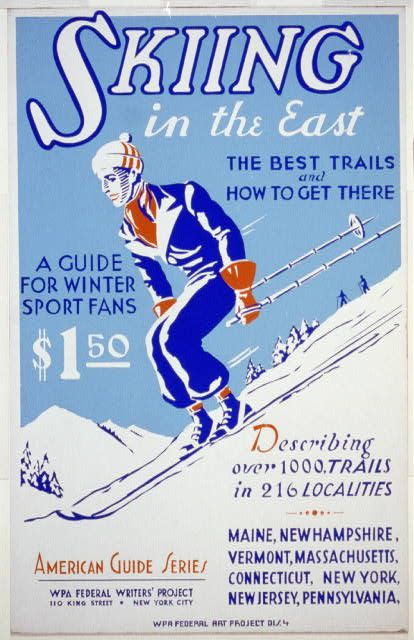

A guide to winter sports in the North-East. (Photo: Library of Congress)

New York City ~ The ship moves along the path of a thousand living steamers, past the ghosts of ten thousand sailing vessels and steamships; vessels that brought the Dutch, the English and their goods, Negro slaves, West Indian run, British textiles, Australian wool, German machinery. Night draws to a close. Bands are still playing behind closed doors of half a dozen nightclubs. The river wind lifts yesterday’s paper the length of a block. A water wagon rolls by. A solitary taxi tracks the wet paving. Good night darling, goodnight, goodnight. A blast from the far-off Narrows whispers through dead streets; spruce from Norway, asbestos from South Africa, German, Austrian, Polish, Italian refugees.

Los Angeles, known to the ends of the earth as the mother of Hollywood, that dazzling daughter still sheltered under the family roof, has other liens on fame and fortune. The country’s fifth largest city, in area the nation’s largest municipality, Los Angeles extends one thin arm to embrace the harbors of San Pedro and Wilmington, and with the other reaches past Santa Monica to the San Gabriel Mountains. Amoeba-like, it has grown out and around many independent communities… so numerous that wits never tire of describing the scene as “nineteen suburbs in search of a city.”… To still others it is a fashionable cafe, a luxurious hotel, a boulevard on which to stroll and see and be seen by the great and near-great, a paradise for the collector of autographs and the hunter of social lions.

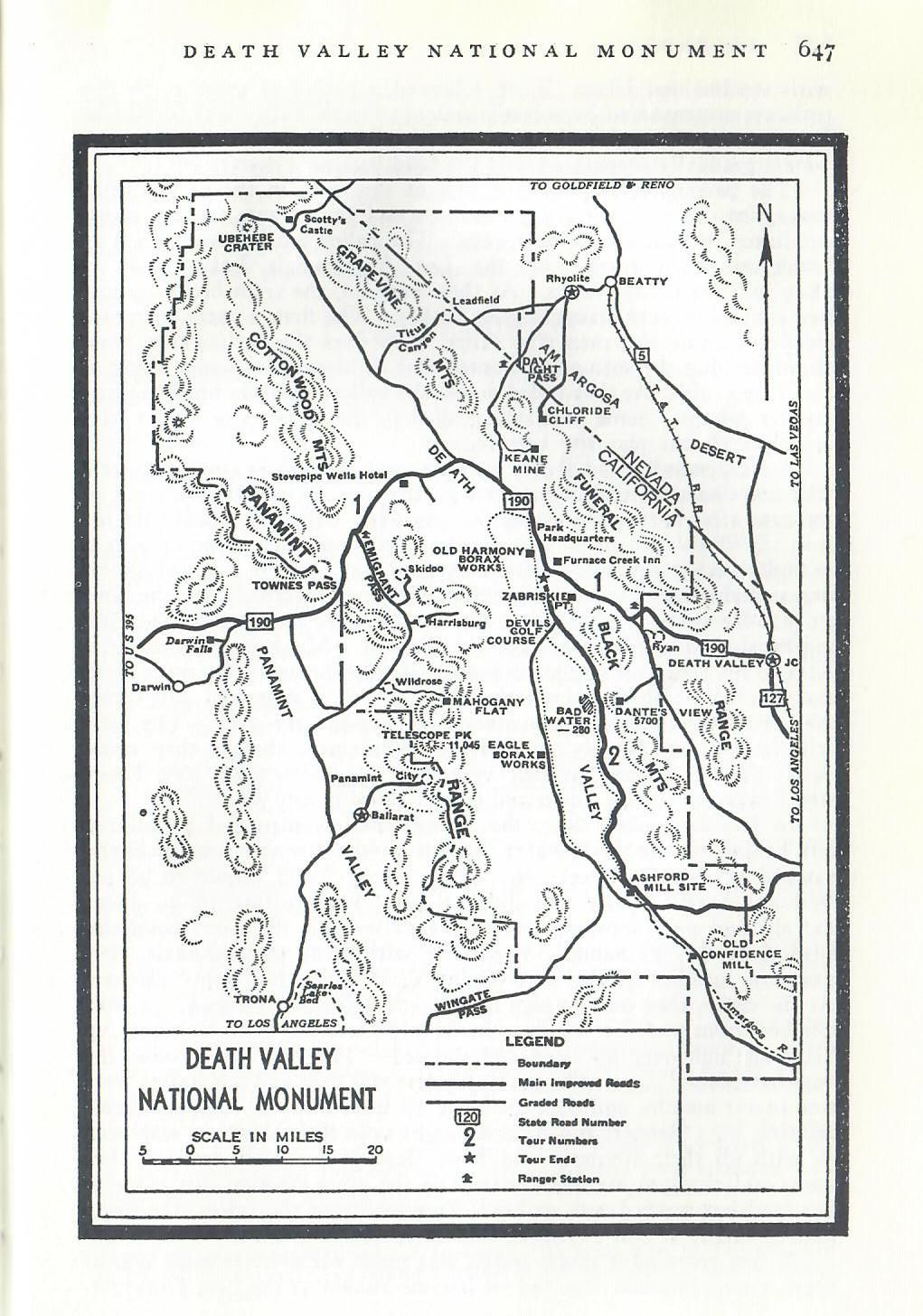

A map from the California guide. (Photo: Courtesy Anne Reddington)

The San Francisco of the old vice-ridden Barbary Coast days is gone, but the traditions established by hordes of happy-go-lucky miners, gamblers, adventurers of all kinds, epicures, and others of the city’s first American population have not been entirely obliterated. Those were the days of laissez-faire, of easy-come-easy-go, of good-natured tolerance, not unnatural in a city where fortunes were made and lost overnight, where a bartender one day was a nabob the next, where today’s bonanza kind was tomorrow’s roustabout.

And finally, a little prophetically:

Massachusetts ~ Tempers wore thin as cherished passages were cruelly blue-penciled, and editorial conferences developed into pitch battles. But out of it all, writers of varied ability and training and of widely differing temperament, thrown together on the common basis of need, shared a new experience – an adventure in cooperation.

That doesn’t just describe Massachusetts; it’s true of the entire American Guide Series.

* Correction: This story was updated to correct Alsberg’s background, and his relationship with Kellock.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook