The History and Uses of the Magical Mandrake, According to Modern Witches

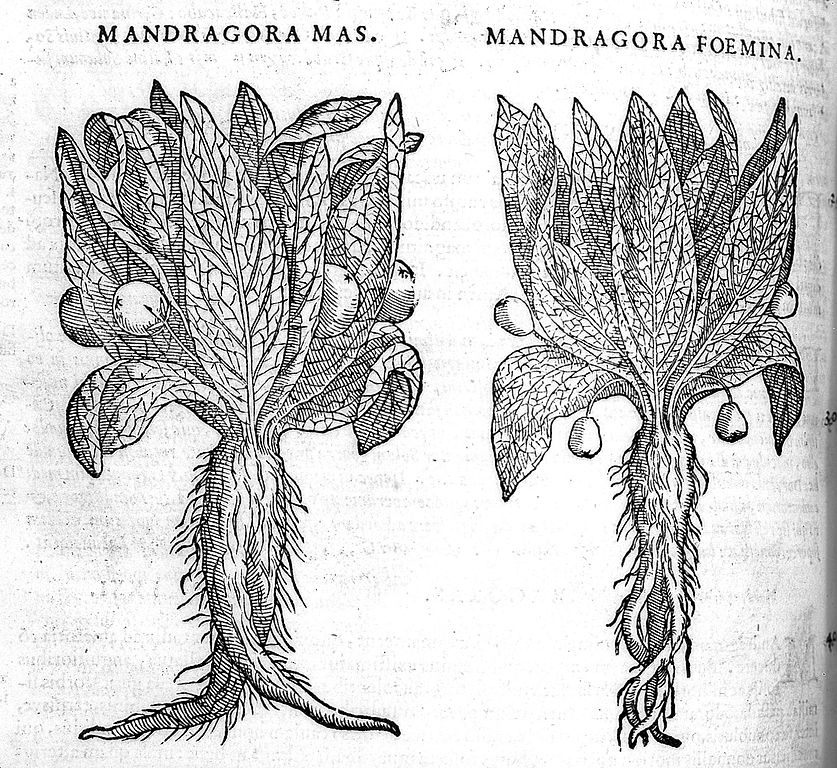

A woodcut of two mandrake plants. (Photo: Wellcome Images, London/CC BY 4.0)

“I have a new little buddy that I’m training to be my personal sorcerer root plant,” Raven Grimassi says.

Grimassi, who along with his wife Stephanie Taylor-Grimassi is a practicing witch, is talking about one of the 20-plus mandrake plants that the couple has been growing at their Massachusetts home.

You may know the plant from Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets as the one with the anthropomorphic stalk that emits a lethal shriek when you uproot it. But the mandrake has a centuries-old history as one of the most important and powerful plants in witchcraft, sorcery, and herbal medicine.

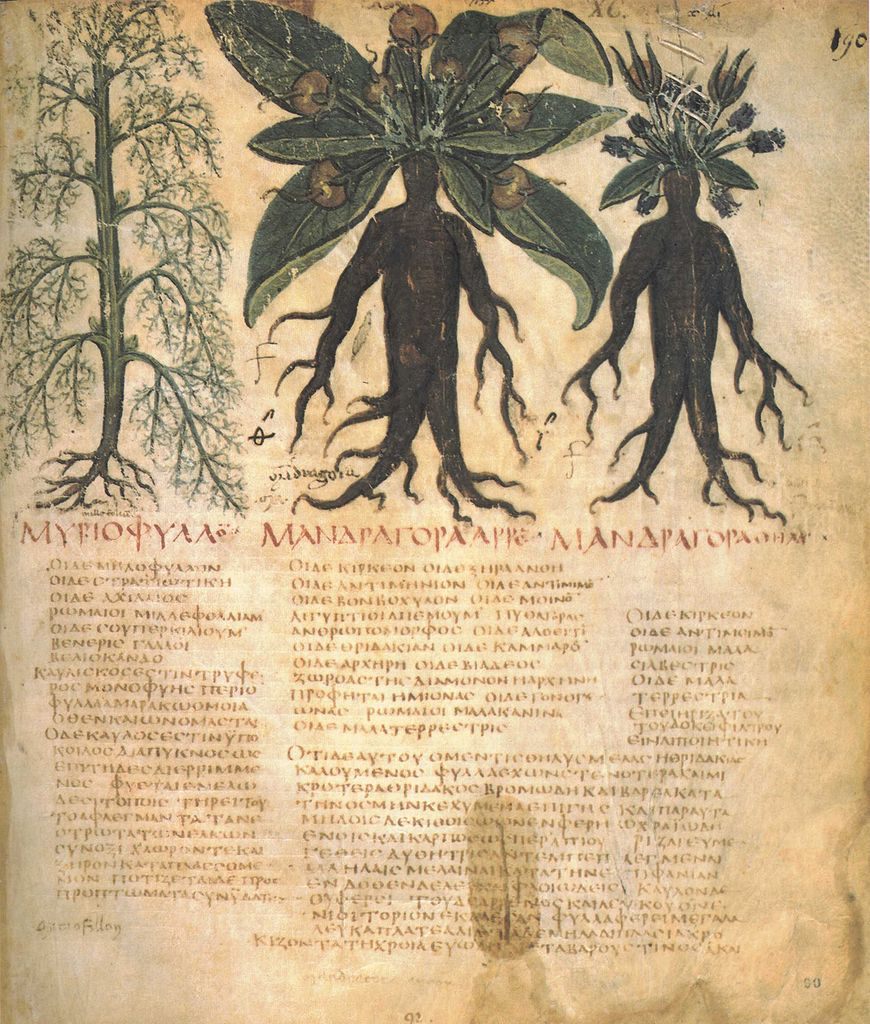

In the Bible’s Book of Genesis, mandrake root helps Rachel conceive Jacob, and in Greek mythology, Circe and Aphrodite are thought to use it as an aphrodisiac. But its powers are not only mythical: a member of the nightshade plant family, mandrake contains hallucinogenic and narcotic alkaloids. Dioscurides, a first-century Greek physician, tells us that a “winecupful” of mandrake root (that is, mandrake root boiled in wine) was used as an anesthetic in ancient Rome. But be careful, he warns—take too much, and one might end up dead.

Dioscurides is one of the first and most important references on the mandrake plant, documenting its appearance along with its medicinal uses. He describes a “male” and “female” mandrake, though we know today that he was describing two different species, Mandragora officinalis and Mandragora autumnalis.

From a seventh-century manuscript of Dioscurides’ De Materia Medica. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

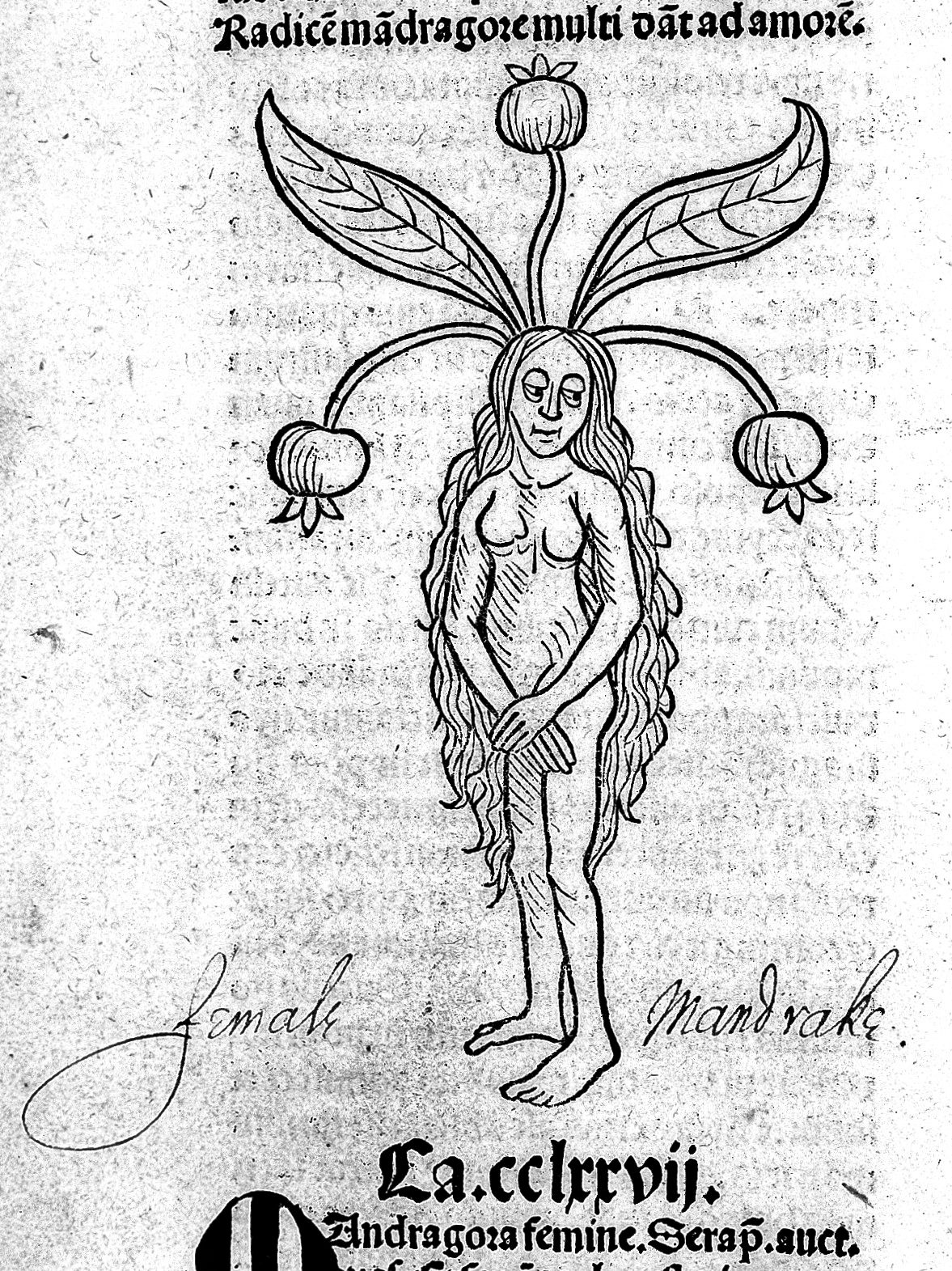

Over the centuries, legends surrounding the mandrake’s different sexes and human shape grew stronger, reinforced by the medieval doctrine of signatures, which claimed that plants that resembled certain body parts could be used to treat ailments of those body parts. As a plant with the shape of a human body, the mandrake was believed to exercise control over the body: it could induce love or conception, or bring good fortune, wealth and power. A mandrake root, shaped like a baby and slipped underneath one’s pillow every night, could help a woman conceive; or, shaped like a woman and carried in one’s pocket, could help a man secure his desired lover. Across Europe, men and women desperately sought out mandrake root to resolve their woes, and fraudsters counterfeited them out of carved bryony root to satisfy the growing demand.

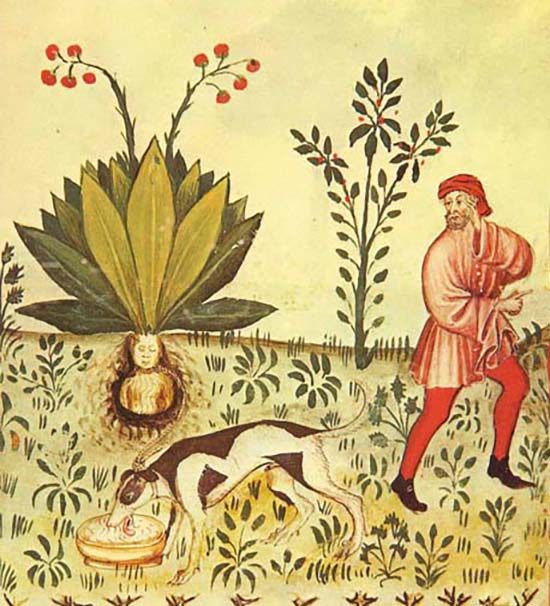

A medieval depiction of a “female” mandrake. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

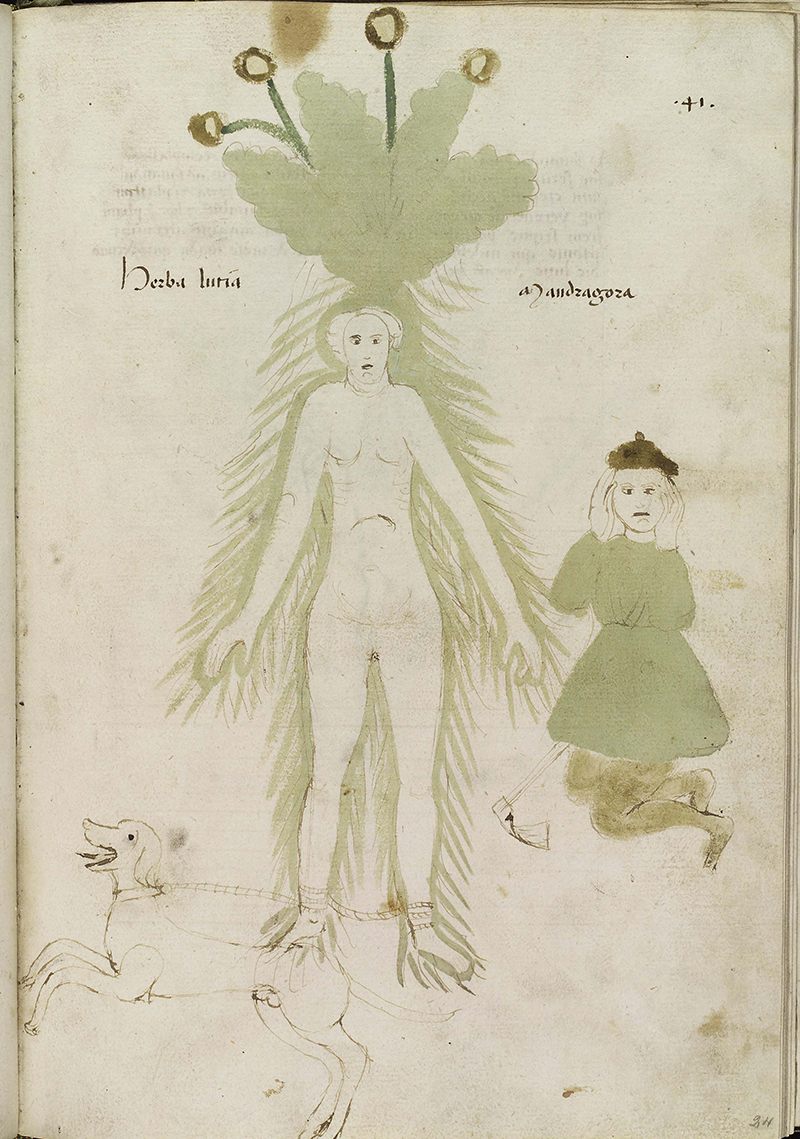

The ages-old legend of the shrieking mandrake, as portrayed in the world of Harry Potter, holds that a mandrake will emit an ear-piercing scream if uprooted, killing the person who digs it up. According to the stories, the only way to uproot the mandrake safely is to plug one’s ears with wax, and tie a rope between a mandrake root and a dog’s tail. Back away from the root and throw the dog a treat, and the dog will lunge for it. The mandrake root will be uprooted by the dog’s sudden leap, and its shrieks will kill the hungry dog. The mandrake-hunter can then unplug their ears and continue the hunt in peace. (As long as they don’t care too much about their dead dog).

An unusual illustration of a female mandrake being uprooted, with the dog attached to the feet of the plant, and a kneeling male figure with his hands to his ears. (Photo: Wellcome Library, Londonn/CC BY 4.0)

Raven and Stephanie believe that it was European witches and sorcerers who made this legend popular, in an attempt to protect the plant from the greedy hands of illicit vendors and common folk. Witches and sorcerers used the roots, fruits, and leaves of the plant not only as charms, but also in potions, ointments, oils and other concoctions to secure the children, love, wealth, or power that their customers and friends desired. If ingested or transmitted through the skin, the alkaloids in the mandrake root worked their chemical magic, inducing excitation and hallucinations, as well as sleepiness—and sometimes, comas or death.

Mandrake illustration from a 15th-century manuscript Tacuinum Sanitatis. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Grimassi stresses that the witches didn’t use these plants to harm people, but rather to heal. “When you concoct a brew for healing, you have to know at what level it becomes toxic,” she says. “Any pharmacist has to have the same knowledge: a drug has to be effective enough to heal but not potent enough to harm.”

By the late medieval period, Christianity had become more and more dogmatic, and sought to stamp out all opposition. Practices relying on traditional herbs and plants such as the mandrake became labeled demonic and dangerous, and rapidly faded from the popular sphere. Witches and sorcerers ended up with a bad reputation, and had to practice in hiding.

A 19th-century illustration of Mandragora officinarum. (Photo: Swallowtail Garden Seeds/flickr)

Raven and Stephanie see themselves as the heirs of this tradition. “None of this really ever went away,” Raven says. Raven and Stephanie’s practice is not a reinvention or rediscovery. They are practicing Old-World Witches, and they have been writing books and lecturing about European witchcraft and magical themes for decades.

Public interest in the mandrake has been growing in recent years, as interest in organic plants and herbal healing has risen. But the Grimassis’ curiosity grew from their studies in the history of European witchcraft. They wanted to practice the theory that they had read about in books. “We wanted to physically see what our ancestors had in their hands,” Raven explains. And they succeeded.

They ordered seeds from a catalogue, and planted the mandrake in their southern California garden. The plants thrived in California, and when they moved to Massachusetts, they carefully uprooted their mandrakes, packaged them in garbage bags, and drove them across the country.

“Of course, there was no shrieking,” Stephanie notes. But the process wasn’t easy. Poisonous and native to southern Europe, mandrakes can’t thrive in the freezing New England soil—but Raven and Stephanie have found a way to make it work. Currently, there are over 20 mandrake plants facing the sunny southeastern windows in the Grimassis’ home in Springfield.

A two-year-old mandrake root. (Photo: Stephanie Taylor-Grimassi)

Through their online traditional herb store, the Gramassis sell mandrake leaves and oil, though they are cautious because the plant can be dangerous if used incorrectly. They strongly discourage their customers from burning or ingesting the leaves, and they don’t sell the roots—which is where the majority of the narcotic and hallucinogenic alkaloids are stored. The popularity of Harry Potter has brought them a few customers, Stephanie says, though many more customers are practicing witches or Wiccans who use the leaves to create a pouch of herbs or charm bag, or oil to anoint candles or a wand.

A 15-year-old mandrake. (Photo: Stephanie Taylor-Grimassi)

Stephanie and Raven care deeply about their plants. They unearth them once a year, usually on Halloween, bathe and anoint the roots, and exchange a few drops of their own blood for a few drops of the plants’ green blood—that is, chlorophyll. They consult their mandrakes regularly to draw knowledge from the earth. Hence Raven’s “personal sorcerer root plant,” with whom he converses regularly. “I talk to him about how mandrakes were viewed as powerful and magical, how witches and sorcerers hunted the woods for them,” he says. “It’s like having a kid, you teach the child to appreciate himself. So you do that with a magical plant, too.”

The hope is that with all this TLC, the mystical plants will offer something to Raven and Stephanie in return. “When I need something, I can go to the plant and ask him, can you help me out?” Raven explains. “And the plant is more predisposed to do that because I have a relationship with him.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook