The Illegal Birth Control Handbook That Spread Across College Campuses in 1968

A group of Canadian teenagers wrote the first popular text on contraception.

The Birth Control Handbook, first printed in 1968 by students at McGill University, was a pioneering text. It was also illegal.

College students are often looking to have sex. But by the late 1960s, they were also looking for more information on sex—on contraception, abortion, and everything in between. In Montreal, Canada, a group of students publicly violated the law to publish a text providing critical information about sexual health.

At a time when such information was nearly impossible to find, copies of their Birth Control Handbook were being distributed by the millions, with requests pouring in from across Canada and the U.S. “We joked that after the Bible, we were probably one of the most widely distributed publications in Canada,” recalls Donna Cherniak, one of the Handbook’s two original authors.

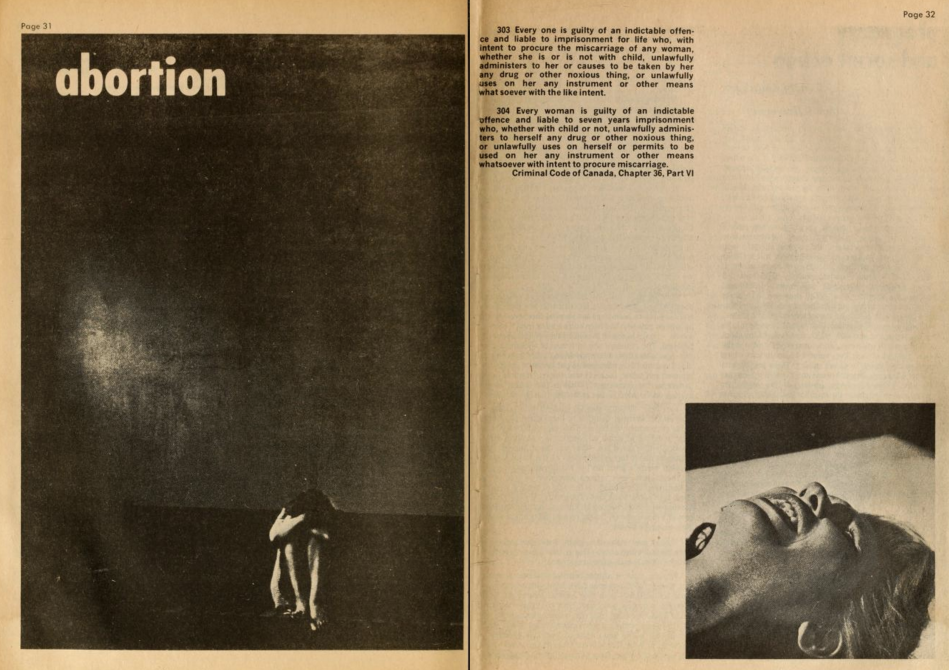

Abortion was a major topic covered in the Handbook. Cherniak emphasizes that they were never anti-baby; they simply wanted women to be given choice. (Image: Canadian Museum of Human Rights/Used with Permission)

Printed in black and white on newsprint, the Handbook went through 12 editions between 1968 and 1975, and took a bold political and analytical approach to sexual health education.

In 1968, under Canada’s Criminal Code, the dissemination, sale, and advertisement of birth control methods were all illegal, and abortion was punishable by life imprisonment. In the U.S., the Comstock Act, passed in 1843 as an “Act of the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use” criminalized the publication, possession, and distribution of contraceptives, abortifacients, and anything related; not until 1971 did Congress remove Comstock’s language about contraception.

To acquire birth control pills in Canada, a woman needed a doctor’s prescription—as well as a husband, since contraceptives were seen only as part of family planning. Though married women in all states in the U.S. were granted access to contraceptives in 1965, it wasn’t until 1972 that birth control was opened up to all women regardless of marital status. But a sexual revolution was underway, and the younger generation was starting to demand freer love with safer health.

McGill University in Montreal, the birthplace of the Handbook. (Photo: TMAB2003/CC BY-ND 2.0)

In 1968, though, most female students had no idea where to start. They didn’t want to become pregnant before marriage, but they also didn’t want to break the law.

“There was really no information out there,” says Laura Kaplan, author of The Story of Jane: The Legendary Underground Feminist Abortion Service. Kaplan has a copy of the first Birth Control Handbook, which she got for free while working with Jane, a Chicago women’s group that operated a secret abortion network between 1969 and 1973. “Women were desperate for this information, so starved for information,” she says. “You wanted it, in as much detail as you could get, as graphic as it could be made.”

When women did manage to get information about health issues like birth control, it was generally from male medical professionals, who were often biased. To get a pregnancy test, you couldn’t just drop into a pharmacy—you had to go to a doctor, unless you could find a women’s group providing the service.

“To have all the information on the various methods of birth control in one place, with pros and cons and what you needed to know about them, was a revelation,” says Kaplan.

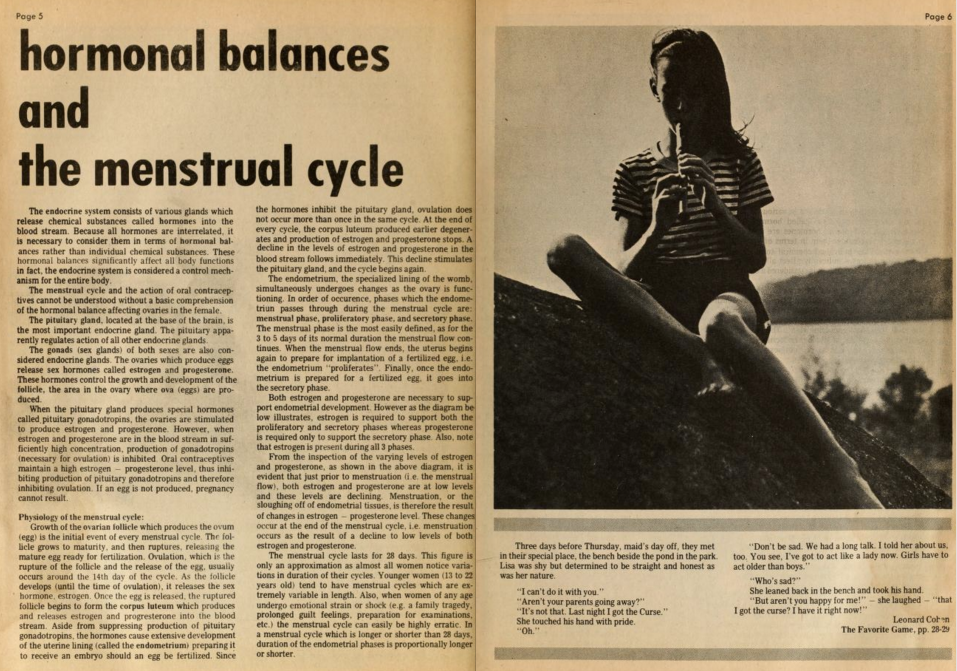

The Handbook introduced the basics of female health. (Image: Canadian Museum of Human Rights/Used with Permission)

Interestingly, it was not women who spearheaded the push for birth control information in Canada, but men influenced by the New Left movement. In 1967, Peter Foster, the 19-year-old Vice President of the McGill Students’ Council, proposed a campus birth control clinic as well as a student seminar on sex education and birth control. The motion passed, and the council formed a Birth Control Committee, which in turn sponsored a seminar, opened the Conception Control Information Centre on campus, and published the handbook on birth control.

All of the above were illegal in 1968. “We figure if we get a lawsuit it will be a lot of fun,” Foster said at the time, when asked about possible repercussions.

Originally aimed at McGill students, the Birth Control Handbook was mostly self-funded, but students at 10 other Canadian universities, as well as Princeton University and the University of Maine, also chipped in. The McGill Daily wrote that the Handbook hoped to “bridge the gap between high school hygiene courses and street corner advisory sessions.”

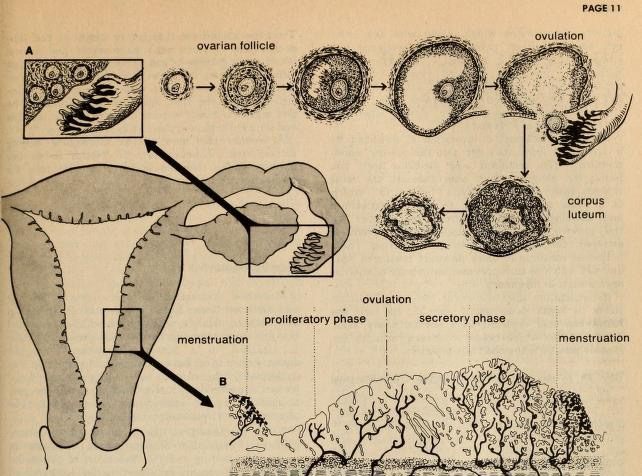

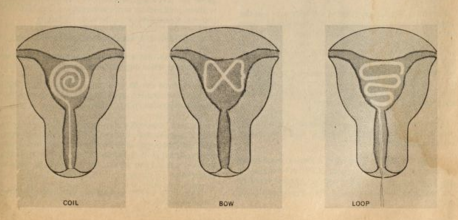

The illustrations and medical diagrams were highly detailed and specific. (Image: Canadian Museum of Human Rights/Used with Permission)

The book’s initial editor-in-chief, undergraduate Allan Feingold, was soon joined by classmate and then-girlfriend Donna Cherniak, and together they generated strong and pointed editorial commentary.

“We went for it,” says Cherniak. “Those were the years in which you thought you could do anything, and you could change the world as well.”

They and other students pored through books in the medical library and consulted medical advisors, compiling detailed information on topics like sexual intercourse, menstrual cycles, surgical abortion techniques (accompanied by prices and statistics), and how, exactly, to contact abortion providers. They also commissioned an illustrator, who, Cherniak says “did a very humane, gentle approach to the anatomical stuff that you don’t find in that many places.”

An illustration of different types of intrauterine devices. (Image: Canadian Museum of Human Rights/Used with Permission)

The first printing of 17,000 copies was snatched up almost instantly by local students. News got around, and requests started piling up. Cherniak remembers boxes of mail coming in—stacks upon stacks of individual letters from women who had seen the Handbook mentioned in a local paper.

The biggest bulk orders came from the United States, where the Handbook was included in orientation kits at colleges like the University of Maine and Trent University. Two years later, in 1970, the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective came out with Our Bodies, Ourselves, which became its own widely circulated women’s health text, translated into 29 languages. It’s interesting how prominent this text remains while its Canadian counterpart has been mostly forgotten.

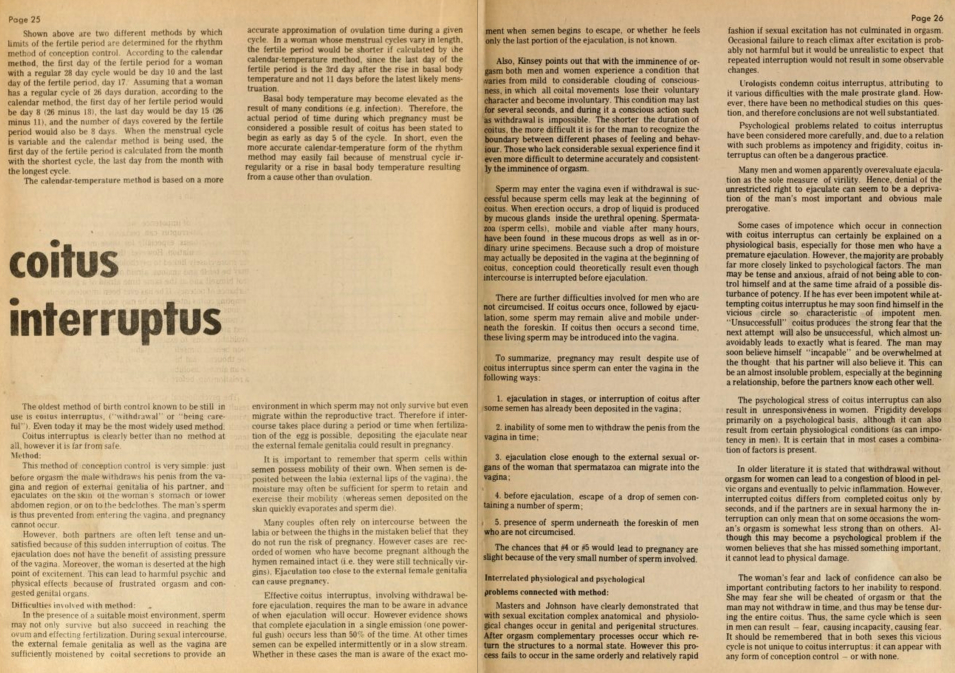

By 1974, though, the small student team at McGill—all the while, writing, researching, and putting it all together—had distributed over three million Birth Control handbooks.

The back cover of the 4th edition. (Image: Canadian Museum of Human Rights/Used with Permission)

Requests for the Handbook were soon after followed by phone calls and letters from women desperate for abortions, which spurred Cherniak and Feingold to set up their own counseling and abortion referral service. Initially run from their apartment in Montreal, and then transferred to a local women’s service center, the couple received women from across Canada and the U.S. When the women needed abortions, Cherniak and Feingold usually directed them to doctor Henry Morgentaler.

A Polish survivor of the Holocaust, Morgentaler began doing illegal abortions in Montreal in 1968 and opened Canada’s first abortion clinic in 1969, when, under Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, abortion was made legal and contraception was decriminalized (many contraceptives, however, still required a doctor’s prescription).

Reflecting on the Handbook, Morgentaler said, “there was nothing like it available… it was a great initiative, a first, a great work of enlightenment.”

“What made it unique, really, was the fact that it combined both information and the politics of the information,” says Cherniak. She and Feingold used the handbook as an opportunity to highlight how issues like race and economics affected women’s access to sexual health resources. They also emphasized broader themes, first women’s liberation and later, overpopulation. For Cherniak and Feingold, this was integral to the work itself.

© 1972 David Miller

Today, the information in the Birth Control Handbook remains as relevant, useful, and necessary as ever. Cherniak, now 67 and in pre-retirement from her job as a general physician, says that when she looks at younger women now, perhaps the first thing she sees is that they’ve understood the need to be financially autonomous. She adds that some people think these issues are over. But there’s still a long way to go.

With abstinence-only sex education on the rise and continuing debates in the U.S. over birth control being covered by health care, it seems like every high school and college orientation kit could still use a copy of the Birth Control Handbook.

Looking back, Cherniak says, “To me, our innovation was to talk about birth control as something that was about people, and not about technique.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook