The Long History Behind Fencers’ Hit-Detecting Electrified Gear

It dates to at least 1896.

(Photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen/CC BY 2.5)

Fencing is a very precise sport. Two fencers battle each other with one of three weapons, a foil, épée, or sabre, which in practice are three very thin rods, with which fencers use to slash, jab, thrust, or otherwise touch their opponent.

It’s like a sword fight—minus the casualties. It is also one of five groupings of sports to be in every Olympics since 1896. But in the modern era, and after the advent of protective gear in the 19th century, there remained the complicated and controversial question of scoring. Fencing resembles nothing more than a traditional sword fight, but in a traditional sword fight the scoring is done brutally and truthfully. Seeing your insides open suggests that there’s little doubt a thrust connected; that gash that’s opened up on you right arm suggests the same.

How then to detect a blade entering human flesh, while not actually doing it?

Electricity, of course. But it took awhile, and in some versions of the sport, electric systems of scoring weren’t widely used until the 1990s, even while other fencing disciplines had been using electric systems for decades. That’s in part because the design challenges of fencing can be surprisingly difficult, even if the solutions turned out to be quite elegant.

In the sport’s early years all it had to rely on weren’t wounds but each fencer’s honor. A successful touch against an opponent was to be met with the opponent saying touché, self-acknowledging the hit, before continuing. Short of that, early fencing also had judges, who would try and discern from the sidelines who’s riposte landed, or, if two fencers simultaneously thrust, who hit first.

None of this, however, was very satisfactory. Humans, of course, are capable of lying, while judges were never going to be able to determine, with much precision, if the tip of one’s foil actually hit their opponent’s belly first. The tip is small and the sport is fast and the fencers’ own movements can be obfuscatory.

Or, as an 1896 article in Britain’s Daily Telegraph and Courier put it: ”It is necessary for the judge to possess the eye of a hawk and the agility of a tiger in order to keep the lightening-like movements of both points well under observation.”

Girls in Washington, D.C. fencing in 1930. (Photo: Library of Congress)

In that same article that the paper reported a possible, radical solution. It was the work of some enterprising fencing enthusiasts who, then, were using a new technology: electricity. Alerting judges when fencers had been hit was as simple as closing an electrical circuit.

The system, developed by a fencer the article refers to as Mr. Little, consisted of an electrified foil, which, when struck against an opponent, completed an electrical circuit, ringing a bell.

A contemporary demonstration of the suit, the Daily Telegraph and Courier said then, “proved an unalloyed success,” even if that success was, apparently, fleeting, since an official electric apparatus wouldn’t be formally adopted by governing fencing bodies for nearly 40 years.

And that system, known as the Laurent-Pagan electric scoring apparatus, proved to be the earliest version that stuck. It was first adopted for fencers battling with épées, and first came into use at the Olympic Games in Berlin in 1936.

That épée fencing was the first to get electric scoring wasn’t an accident: the rules of the sport, dictating that any part of your body can be a target, are relatively straightforward, meaning that an electric system wouldn’t have to be much more sophisticated than sensing whether the tip of one’s épée made contact with any part of the opponent’s body.

But foil fencing, which did not get electrified for another 30 years, and sabre fencing, which wouldn’t be electrified until 1988, presented designers with more complicated problems.

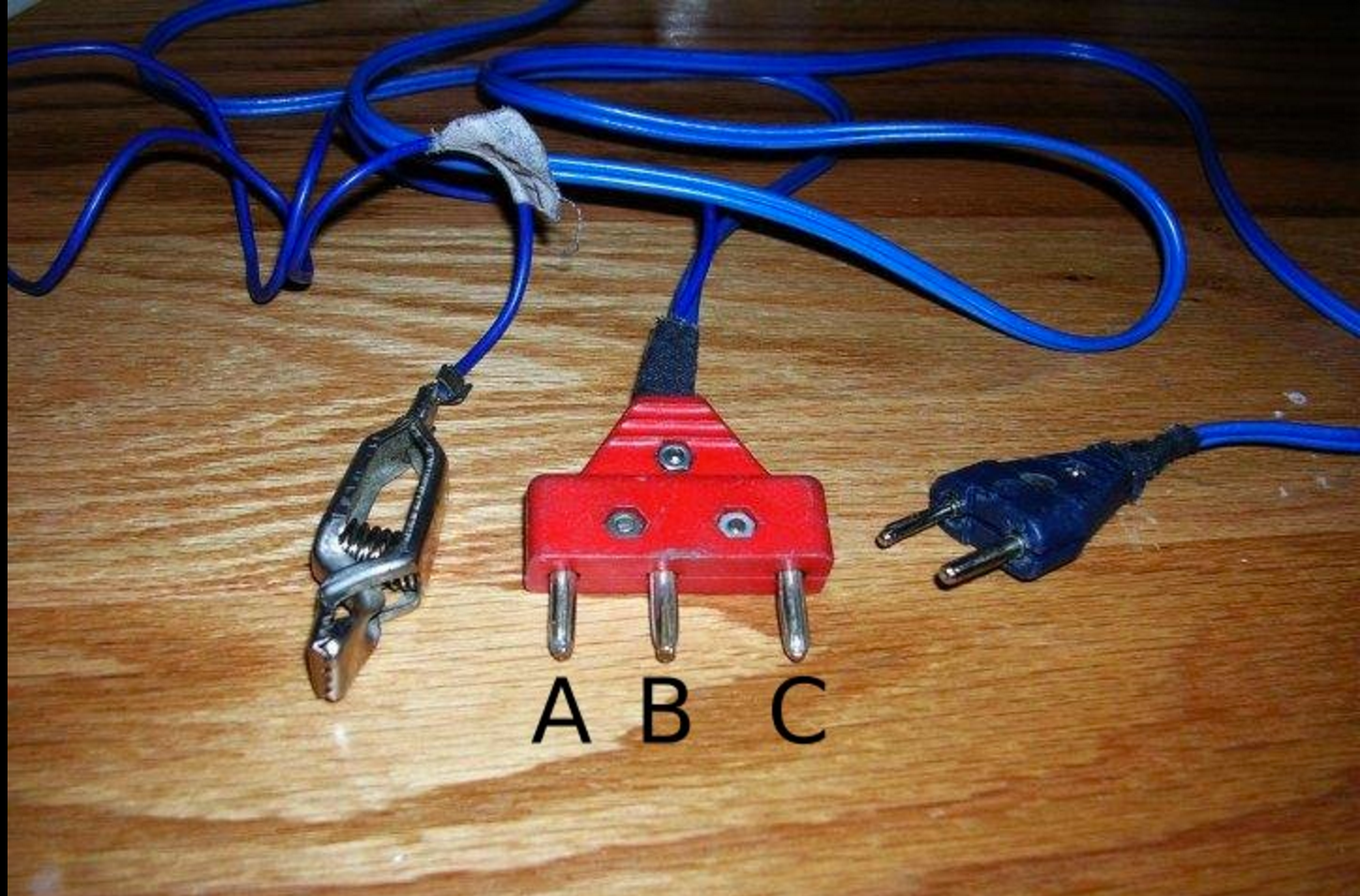

A body cord for foil and sabre fencing. (Photo: Emerson bb/CC BY-SA 4.0)

That’s because in foil fencing—which is the oldest, most classically-cherished form of the sport—some areas of the body are off-target, meaning that an electrified metal rod trained to signal at the moment it touches any part of the body would be functionally useless. So designers had to find a way to help the foil differentiate between the target and off-target parts of the body.

They did this through the use of lamé, a fabric weaved in part with an electrically-conducive metal, like copper. Fencers wear this fabric over the parts of their bodies that are targets in foil fencing: their chests, their necks, their backs, and their groins. The scoring apparatus was developed to work in concert with the lamé, registering it as a different hit than if the foil hits either the opponent’s foil or a part of their body that isn’t covered in lamé.

Whereas in épée fencing the system could set off two potential signals—hit or not—foil needed to accommodate three: a hit, an off-target hit, and no-hit.

Sabre fencing is even more complicated, in part because touches with the entire blade—not just the tip—count. In addition, a touch to the the mask needs to register as a hit, while off-target hits, which stop the action in foil fencing, need to not register, allowing the fencing to continue.

It wasn’t, in fact, until the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona that electric sabres were widely used—a year when the world’s first smartphone was introduced. Fencing technology, in other words, takes a little bit longer to evolve, even if the sport itself has been practiced since time immemorial.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook