The Long, Politically Fraught History of Seeds in the U.S.

We’ve come a long way from the government giving away free seeds.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

When you’re looking to plant a fresh urban garden, it’s natural to hit your local store and buy a bunch of tomato seeds, perhaps some carrot seeds, and maybe you’re in the mood for some spice, so you add a couple of habanero seeds to the cart.

Soon, you might plant these seeds in the ground, without even giving a second thought to the fact that you showed your support to the commercial seed industry. It’s a heckuva lot larger than you’d think, bringing in $45 billion globally each year according to the American Seed Trade Association.

Now, you might be wondering to yourself, “Wait, $45 billion? How? Can’t commercial farmers just use the seeds left over by the plants they grow?”

Well, this issue is way more complicated than that. And, largely, you can thank genetically modified crops, and, more specifically, the 1980 Supreme Court case that paved the way for them.

In Diamond v. Chakrabarty, the court then affirmed (in a narrow 5-4 decision) that genetically modified organisms, or GMOs, could be patented, setting the stage for the rise of seed industry giants.

“While laws of nature, physical phenomena, and abstract ideas are not patentable, respondent’s claim is not to a hitherto unknown natural phenomenon, but to a non-naturally occurring manufacture or composition of matter—a product of human ingenuity ‘having a distinctive name, character [and] use,” Chief Justice Warren E. Burger wrote.

This decision, while involving a form of bacteria that could break down crude oil, proved a major turning point for the seed industry, and allowed GMOs to propagate widely. This is the seed, in other words, that allowed the agricultural company Monsanto to grow into a multi-national giant.

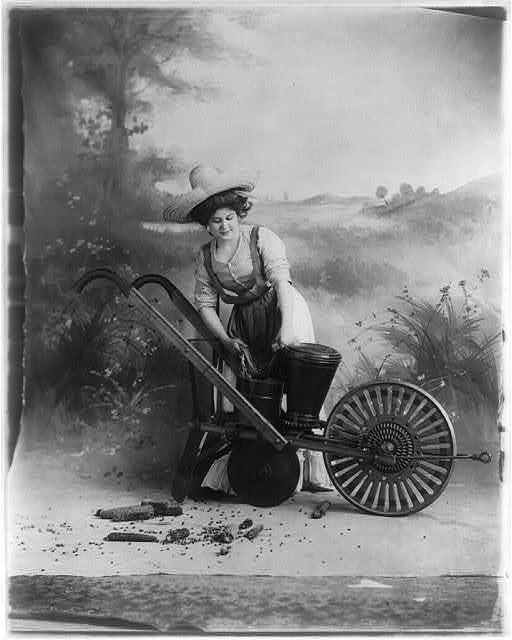

It’s also quite the change from the time when the federal government used to seeds away for free.

No, really. They did that. When the American Seed Trade Association got its start in the late 1800s, the seed business was far from the massive success it is today. In fact, prior to its launch, many seed companies went under.

The culprit? The federal government, who spent nearly a century giving away seeds for free through a variety of organizations, starting with the agricultural arm of the U.S. Patent Office, eventually giving way to the USDA upon its 1862 founding.

For nearly a century, the federal government was organized around the reality of the economy, which is that it was still strongly agrarian. Many early post offices were hubs for picking up seeds. It wasn’t a cheap program, either: At one point in the late 1800s, roughly a third of the USDA’s budget was dedicated to distributing seeds around the country. And some political parties wanted the seed program to go even further.

All of this, though, didn’t stop more seed companies from starting up, despite the long odds for success. Eventually, the American Seed Trade Association was formed in 1883, with the free seed program the companies’ primary issue. It took a few decades of lobbying, but in 1924, things finally changed in their favor, when Congress ended the free-seed program.

Around that time, the seed industry came up with its first hybrid corn seed, which helped make the case that the commercial market could create seeds that produced better yields than the federal government. That helped set the stage for the commercial farming and food industry we have today.

To this day, commercial seed-growers understandably see the early period as the “bad old days,” and, in modern times, are still fighting for their right to monetize their seeds. Take a 2013 Supreme Court case Bowman v. Monsanto Co., which pitted Monsanto against a farmer who wanted to reuse his genetically modified seeds. The seed industry argued that the government’s free seed program ultimately harmed the seed industry by removing incentives for farmers to develop their seeds, and therefore, their crops.

“Early seed breeders had little incentive to make costly investments in developing more productive plants because the free seed program crowded private breeders from the marketplace,” the brief, filed by 21 different industry organizations, stated. “Additionally, without intellectual property protection, seed breeders had little control over the fate of their genetic material; purchasers were not barred from saving seed or from selling the new seeds they grew to others for planting purposes without compensating the breeder.”

(The Supreme Court ultimately sided with Monsanto in a unanimous decision, finding that seeds remain patented even after you re-grow them.)

We may not have federally mandated free-seed programs anymore, but one thing we do have more of now than we did in 1862? Libraries.

And some of those libraries, more than 300 in the U.S. alone, are in the seed business.

Seed libraries, or grassroots-level seed exchange programs, generally work like this: you pick up the seeds you need, grow something in your garden, then when you’re done, you return some seeds back to the library. It’s a good idea, but the problem is, the practice is illegal in some states due to broadly-written agricultural legislation—legislation that, in many cases, also bans you from exchanging seeds with friends.

There has been at least one case, in fact, where a state agriculture department came down hard on a library for the heinous crime of seed-sharing.

In 2014, the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture told a library in Mechanicsburg that they were in violation of a 2004 state law because they allowed people to plant seeds from the library, with the promise that they’d offer up new seeds from fully grown plants later on. The department told the library that this was a bad idea—the seeds had to be tested, had to come directly from commercial seed companies, and at the end of the growing season, all the extra seeds had to be thrown away.

“What they proposed to do at the library fell under the definition of seed distribution, and if you’re a seed distributor, you fall under the provisions of the act,” Deputy Agriculture Secretary Jay Howes told the Wall Street Journal.

When discussing the issue, Cumberland County Commissioner Barbara Cross suggested that the seed library created a legitimate threat to the food supply, and that it was important to get on top of the issue while it was still relatively manageable. She also managed to introduce the word “terrorism” to the conversation.

“Agri-terrorism is a very, very real scenario,” she told the Sentinel. “Protecting and maintaining the food sources of America is an overwhelming challenge … so you’ve got agri-tourism on one side and agri-terrorism on the other.”

Eventually, the library made a deal with the state—it would no longer let gardeners bring seeds back to the library, and would only sell donated seeds from corporations. Crisis averted, apparently.

The thing is, though, is that the controversy highlighted to the public that these laws existed in the first place. And while they were meant to discourage the threat of Frankenseeds and prevent diseased plants for propagating in the commercial farming system (a genuine concern, considering the mess we know that is), there’s evidence that they could have the side effect of putting gardeners on the hook for sharing seeds with their friends.

To the layman, it sounds—what’s a good way to put this?—insane.

Fortunately, there are organizations that have been working on this issue. One of them is the Sustainable Economies Law Center, a legal group focused on environmental issues.

They have been active in lobbying for updated laws and exceptions to the laws currently on the books for seed libraries around the country, particularly in California, where the group worked to get AB 1810 on the books—successfully, as the act was signed into law back in September. The law clarifies that seed sharing laws are not meant to cover non-commercial exchanges like libraries.

As for Pennsylvania, there’s some good news on that front as well: Earlier this year, the state’s agriculture department clarified that non-commercial seed exchanges were not covered by the state’s Seed Act of 2004, which allowed the library in Mechanicsburg can go back to exchanging seeds without any corporate influence.

Brian Snyder, the head of the Pennsylvania Association for Sustainable Agriculture, welcomed the change of heart by the state. While Snyder said the law had its place, it was necessary to clarify it wasn’t intended for grassroots-level gardeners.

“Seeds are a basic element of human life and wellbeing,” Snyder said. “Without this kind of informal cooperation among neighbors, that well-being is very much at risk.”

If you go into a Lowe’s and buy some seeds, you will most assuredly see the seed packets labeled with such phrases as “GMO-free” and “organic,” two phrases that you would not have seen on seed packets two decades ago.

But we can’t make that assumption anymore. As a culture, we’ve been having a longstanding debate about whether we want our food to have GMOs in it, whether it should be labeled, or even whether it’s a big deal. The federal government’s recent law on this issue, which allows labeling to be hidden behind an electronic code, definitely didn’t make some folks happy, because the devil is in the details, though a few critics out there claim that GMO labeling is a form of fear-mongering, anyway.

The portion of the seed industry that directly targets gardeners, at the very least, seems to have found its line on GMOs: If you care enough about your food that you’re willing to plant it yourself, you don’t want reprogrammed seeds.

The problem is, though, unless you’re a master gardener and living 100 percent farm-to-table, someone else is making that decision for you.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook