The Man Who Develops the World’s Found Film

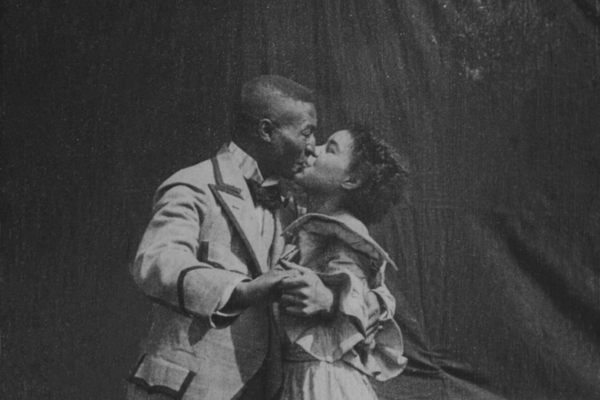

The Rescued Film Project rediscovers forgotten moments captured on camera.

It’s happened to everyone. You’re rifling through a bin at a thrift store, or a garage sale, or an unmarked box in your attic, and you find an undeveloped roll of film. The thought crosses your mind: should I get this developed? See what’s on it?

But who has time these days to find a convenient place to develop it, let alone pay for the process.

That question, and that obstacle, are exactly what led Boise, Idaho-based photographer and video producer Levi Bettwieser to start a website called the Rescued Film Project. After years of stockpiling his own thrift store finds, amassing about 140 rolls of 35-millimeter film, he spent a day developing them all.

“I was astounded by the amount of images I was able to get off just those few cameras in my local area,” says Bettwieser. “And I connected with them because a lot of them looked like images I had in my photo albums as a kid.”

That was three years ago. Bettwieser quickly tapped out his local thrift store supplies and started going after rolls sold through online auctions.

His site posts his finds, as well as soliciting donations of other people’s undeveloped film. In those first batches he developed there were all the usual things people snap photos of: celebrations, vacations, loved ones. Nothing “too astounding” according to Bettwieser. But one series of images stood out.

The images were surreal, otherworldly. “It seems to be these two young boys who are sharing and taking pictures of each other under water and there were some really incredible bubbles,” he says.

Bettwieser wavered about his decision to put the found images online, as he didn’t want people to feel like their privacy had been invaded or that they were being made fun of.

But when he took the plunge, he also offered up his services to people with undeveloped rolls. Volunteers send their film to him after signing over their rights to the images and Bettwieser keeps the negatives. In many communities, the resources to develop such film is vanishing or gone. Large photo processors, like Walmart, typically don’t have experience handling different sizes of film, degraded film, or black and white film. And even where experienced photo processing facilities exist, some people simply don’t want to spend the money on film that may or may not offer up images. For those who don’t want to give up the rights to their images, Bettwieser recommends places they could pay to have it developed.

“I don’t care who’s processing the film as long as it gets rescued,” he says.

Since he started soliciting film, Bettwieser has received about 140 donations, and some of those have been single donations of over 100 rolls. He receives around three donations a week and has a backlog of around 2,000 rolls to process and several hundred images to scan. There are over 16,000 images in his archive. The project is a one-man operation that he works on before and after work and on the weekends.

“When it starts to feel like a job or work that’s when I have to step away from it,” he says.

Most of the content he finds falls in the G-rated to PG category. He does find the occasional naked photo, which he doesn’t publish. Those are rarer, he says, probably because people were more careful about taking revealing photos when they knew a processor would have to look at them.

“From the earliest images all the way up to my newest images, they usually revolve around holidays, typically Christmas and Halloween,” says Bettwieser. “Those are two of the most common types of images I get. Birthdays and birthday cakes. I probably have more images of birthday cakes than I do actual birthday parties, which is kind of interesting. Cats and dogs. There’s a lot of pictures of cats and dogs, and vacations.”

He has uncovered more unusual fare, though, such as several images from World War II that made a splash online when he published them in 2015. Those images were the result of an $800 investment, his largest and most “nerve-wracking” purchase to date.

And there were the 10 rolls of black and white 35mm film from New York that appeared to be the work of a voyeur who photographed women on the street from their window.

“But he was also a great photographer, there were some really amazing landscapes of the New York skyline with the World Trade Towers and fireworks at night,” says Bettwieser. “That was probably one of the most interesting batches I got in terms of I had several rolls from one photographer which gives you a better sense of who they are.”

He also received a cache of black-and-white images of California car crashes that depict vehicles slid off the road and people being carried away in stretchers. One roll of film offered up images of an arctic voyage aboard a ship and with a biplane.

The images he unearths have tantalizing, if unknowable, mysteries embedded in them.

“You see a bunch of Backstreet Boys posters on the wall, it’s an early ‘90s kid,” says Bettwieser. “It’s fun, but it’s also frustrating, sitting there and trying to tell the story. I love pictures that have a lot going on in the background. A lot of people, the first thing they’ll look at is the person in the photo, and they’re usually smiling like you do in a photo, but you don’t know if they’re actually happy in that moment. Looking at their environment tells you more about them, what’s on their shelves, how nice it is, how clean it is.”

Eventually he would like to make his site more searchable, with metadata and crowdsourcing so that people can reunite the images with people close to them. This happened once, when he posted a photo on Instagram and a Portland woman recognized her father at a family gathering where she was given a dog as a childhood gift.

One thing, though, is notably missing—selfies. Bettwieser says he does occasionally find photos of the camera-wielder but that they usually show up at the end of roll when someone is trying to “burn off” film.

“So many pictures in the archive are the truest form of what’s going on at that moment and there’s no self-editing, no instant playback, people’s eyes are closed,” says Bettwieser. “They’re more honest.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook