The Manmade Marvel of the Baltimore Sewers

Filters at the Back River sewerage plant in Baltimore, 1973. (Photo: NARA)

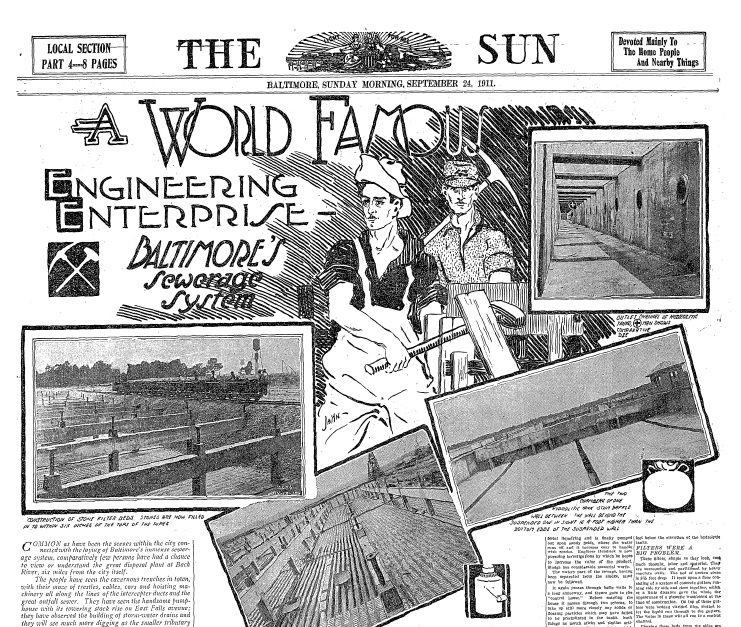

In 1909, Baltimore’s sewer system was nearing completion and the local press was in a tizzy, proclaiming it an “unexcelled marvel of the engineering world.” Newspapers bragged that “the sewers are of such size as to remind you of the ones in Paris,” a flattering comparison as the Parisian sewers were (and still are) a popular tourist destination. Calvin Hendrick, the Baltimore Sewerage Commission’s chief engineer invoked a higher power as he boasted that “we are getting nearer to the laws of God” in reference to city’s innovative wastewater purification process.

If the sewers weren’t quite divine, their construction was a point of civic pride for a metropolis striving to attract businesses, residents, and tourists, not unlike the Baltimore of today. Hendrick devoted heroic efforts to publicity, worried that his project was destined to vanish underground. “The public would be amazed,” he remarked, “if they could realize what has been accomplished…I only wish that the people of Baltimore could see it.” It was a prescient concern: soon after construction stops, most infrastructure becomes taken-for-granted.

Baltimoreans had especially good cause for their amnesia. Who would want to remember life before public sewers?

The need for sewers in 19th-century Baltimore was abundantly clear to those who endured the “2,000-horse-power smell” of the city’s harbor. There, streams of human waste, trash, and industrial runoff converged and stewed under the summer sun, breeding deadly typhoid fever. City code required indoor toilets, but it was up to individual property owners to build cesspools, cisterns, or gutters. These emptied into an unfortunate stream called the Jones Falls; its polluted course ran from the wealthier to the poorer areas of town and finally into the harbor. An 1890 news story claimed that harbor steamboat passengers “were known actually to faint from the effects of the vile smell.” Baltimore was one of the last major American cities to build a public sewer system.

Why, while other municipalities broke ground on sewers, did Baltimore languish through a half-century-long public health nightmare? It’s a historical puzzle with particular relevance today, as many cities struggle to upgrade their aging infrastructure. Some pieces of this puzzle are familiar enough: political gridlock, cash-strapped governments, and NIMBYism. Other pieces seem a bit more antiquated, like the notion of airborne miasmas and toxic sewer gases.

“Night soil men” manually emptied Baltimore’s 20,000 cesspools prior to the construction of public sewers. (Photo: Public Domain)

The halting march towards sanitation began in 1859, when Baltimore appointed its first sewer commission. Based on reports from eminent physicians and engineers, the commission decided that switching from private cesspools to public sewers would cure stench and disease. However, a slew of opponents brought their political power to bear on City Hall. The cesspool-emptying industry fought to protect its business. Oyster fishermen protested that sewage piped into the Chesapeake Bay would contaminate their catch. Even some medical men warned that noxious “sewer gases” could strike people dead in their own homes. Finally, taxpayers refused to foot the bill when they could dump waste into the Jones Falls for free, the method preferred by many downtown office buildings and by City Hall itself.

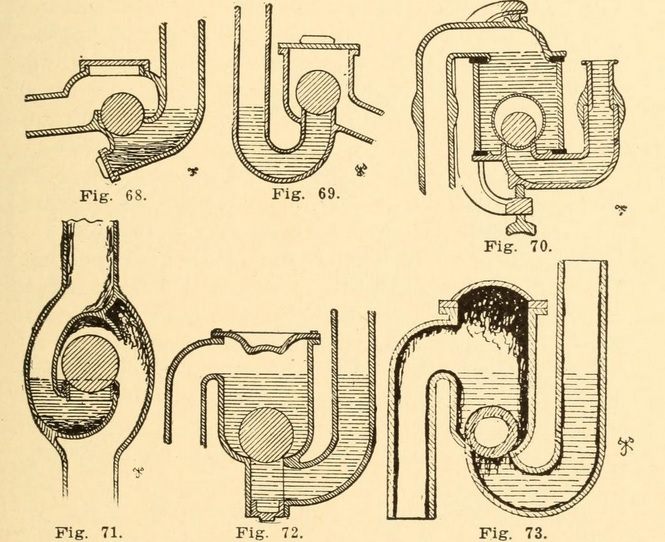

Architect J. Pickering Putnam analyzed a wide variety of plumbing traps for their microbe-fighting properties, from the 1911 book Source: Plumbing and Household Sanitation. (Photo: Public Domain)

For all these reasons, the sewer commission’s report went nowhere. Every few decades the smell and disease triggered a crescendo of civic outrage, but two more commissions met the same gridlocked fate. If it weren’t for a disaster that leveled the city’s downtown, it’s unclear when Baltimore would have broken free from municipal inertia.

The Baltimore Public Works Museum exterior, also the operating Eastern Avenue Pumping Station. (Photo: Alan Levine/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

“The Great Fire of 1904 was a godsend for the sewers,” said Department of Public Works spokesman Kurt Kocher in a presentation last month to the Baltimore City Historical Society. “After the downtown was incinerated, civic pride was at a peak.” The people and politicians of Baltimore determined to rebuild the city better than before. It helped that the fire coincided with the rise of the Progressive movement, a turning point when entrenched ward politics gave way to a spirit of scientific management. It was ambitious technocrats like chief engineer Calvin Hendrick who ensured that the system that finally got built was a modern wonder. In Kocher’s generous formulation, Baltimore “was at the forefront of wastewater treatment, though it took a long time to get there.”

Public anxiety about sewer-borne contagion did not disappear with the new system; in fact, it created a booming market for dubious germ-proofing products, such as elaborate multi-chambered plumbing traps and carbolic-acid sprays. Before 1904, open-air gutters flowed in one direction from the wealthy northern suburbs to the poor neighborhoods around the harbor. New, enclosed sewer mains enabled two-way traffic: waste flowed down, but gases rose up, or so the alarmists imagined. They insisted that germs from the slums would penetrate the water-closets of the elite.

This fear of contamination came in part from medical authorities, but it also expressed the perceived danger of disrupting the city’s social hierarchy. Within a decade, as public sewers became an invisible part of everyday life and no-one died from sewer gas, people forgot about the transgressive potential of plumbing.

The Sun’s 1911 cover story on the wonders of modern sewerage:“A World Famous Engineering Enterprise: Baltimore’s Sewerage System”, September 24, 1911. (Photo: Public Domain)

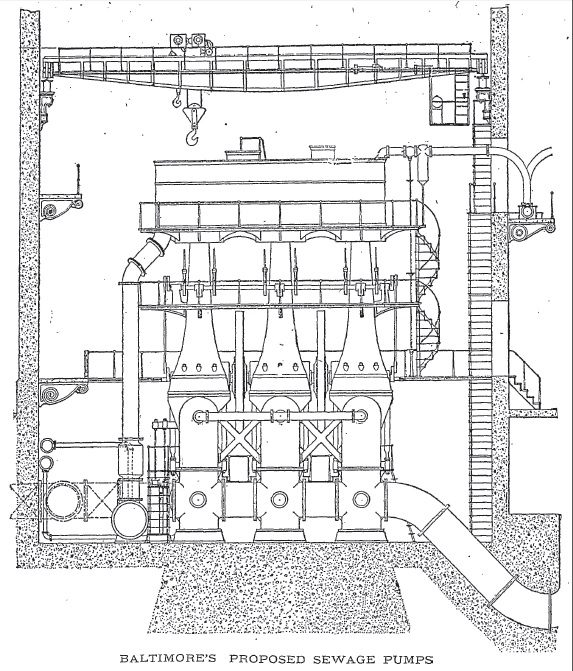

The ultimate question for Baltimore’s sewers was where their contents should wind up. Hendrick promised cutting-edge technology that would leave outflow in “such a state of purity that it will pass muster with many water systems in the country”–practically clean enough to drink. However, none of the city’s neighbors would host the fragrant process of filtering and purifying 300,000,000 gallons of sewage per day in open-air pools, even if it was a marvel of modern engineering. The Sewerage Commission zeroed in on the town of Essex, in an area called Back River known mainly for its red-light district. Kurt Kocher of the DPW said that “the toll fell on Essex as a kind of anti-vice measure,” since local businesses couldn’t fight the sewage plant without exposing their illegal activity. Nevertheless, one brothel proprietor successfully sued the city for losses incurred due to odor.

A 1906 diagram the Eastern Avenue pumping station, which still moves sewage from the Inner Harbor to Back River. (Photo: Public Domain)

Hendrick would be dismayed but hardly shocked by the situation just over a century later. Errant sewage is a staple of local news. Broken and overflowing pipes follow every major storm; last year, NPR highlighted Baltimore’s system as a case study in decaying infrastructure, calling it a “time bomb hidden under the streets.” Today’s narrative is about disinvestment and failure: cities like Baltimore might continue to let their public works crumble until something catastrophic happens. Upgrades mean massive city debt and higher bills for residents, a tough sell politically.

It’s hard to find traces of the optimistic Progressive-era narrative, since the Museum of Public Works, which showcased the history of water, gas, electricity, and roads, shut its doors in 2010. You can still visit the Eastern Avenue pumping station and peer through a fence at a fantastic scale model cross-section of a city street, a reminder of how citizens and policymakers once overcame decades of inertia to build a world-class piece of public infrastructure. The sewers might seem like a bleak place to go searching for civic pride–they’re full of rats and shit, while tree-lined streets are beautiful and the art museum is full of great art. But it’s our messy invisible systems that sustain the veneer of civilization. Celebrating this “city beneath the city,” and understanding the obstacles that plagued it then and now, offers an alternative to the story of inevitable decay.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook