The Modern Manhunt Began With An Arrest by Wireless Telegraph

Morse code messages and bowler hat cameras were the Twitter and cellphones of the Edwardian police chase.

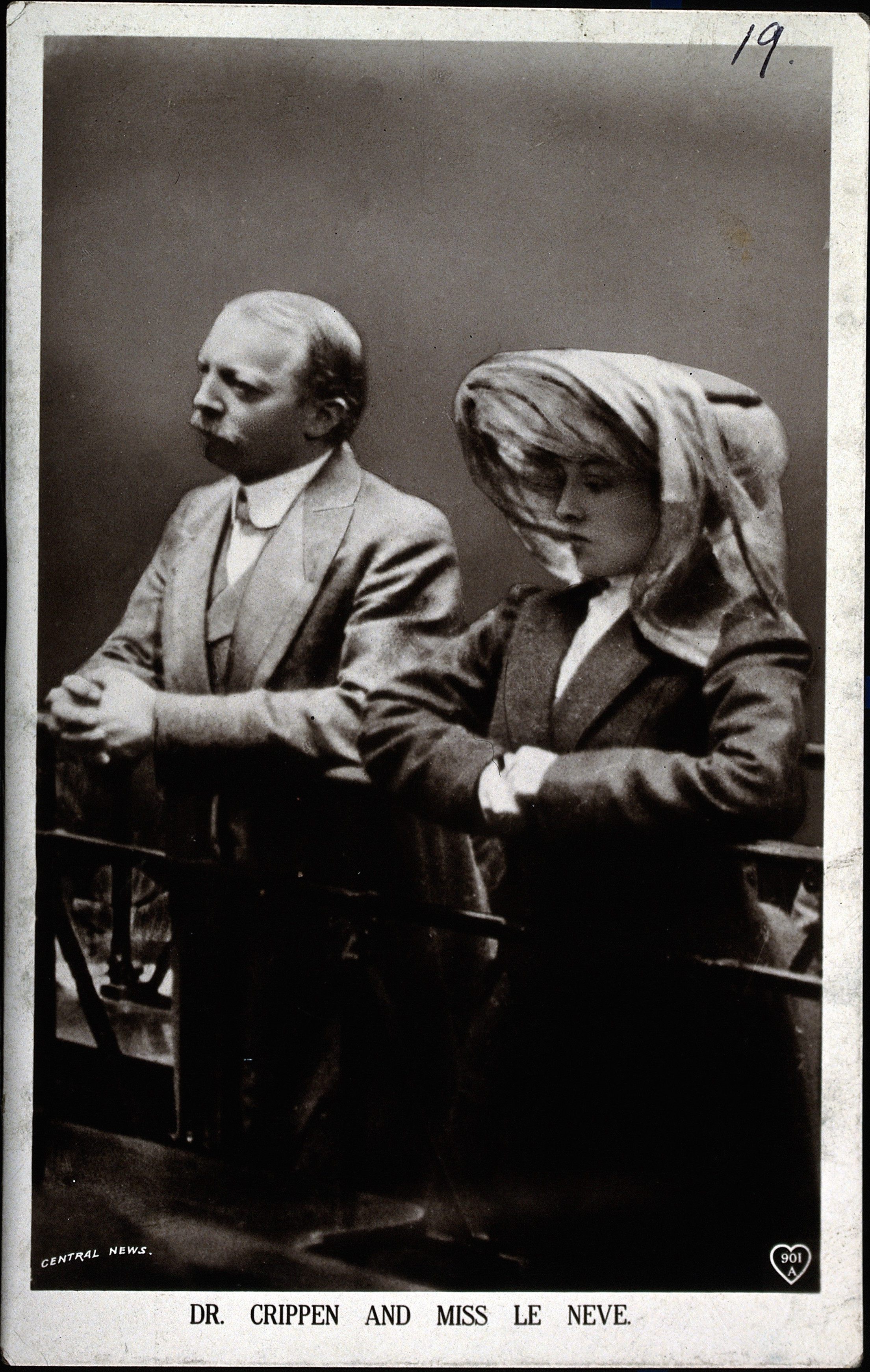

Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen, accused wife-murderer, and his companion, Ethel Le Neve, at their criminal trial in 1910. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ggbain-08612)

In the 21st century, a major manhunt is usually accompanied by breakneck Tweeting, rampant Reddit speculation, blurry eyewitness videos on Periscope, and a CNN reporter saying something of questionable veracity on live TV.

Back in the Edwardian era, the frenzied search for a fugitive went a little differently. Take the case of Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen, whose brazen escape in the wake of a murder accusation prompted a thrilling transatlantic police chase and capture on the high seas. It was the world’s first case of arrest-by-wireless-telegraph, and, though the technology worked a little slower, was no less enthralling for police, the media, and members of the public who followed along.

In July 1910, things were going rather poorly for Dr. Crippen, a 47-year-old American homeopath living in London. Crippen’s wife, actress Belle Elmore, had not been seen since the couple hosted a party at their home on January 31, half a year earlier. Meanwhile, Ethel Le Neve, Crippen’s comely stenographer, had begun swanning around in Elmore’s furs and jewels, and appeared to have moved in to the house.

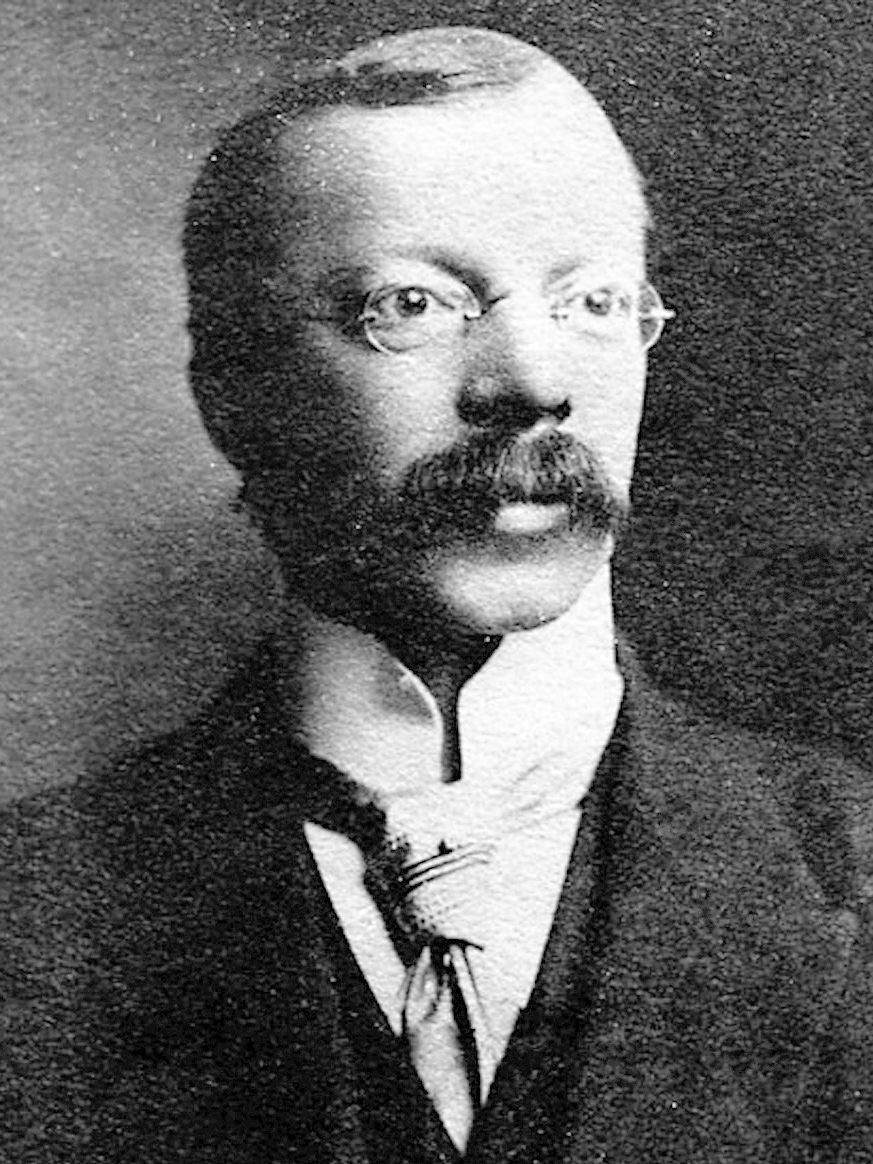

Dr. Crippen, unaware of just how much trouble he’s about to be in. (Photo: Public Domain)

Crippen told anyone who inquired about these odd circumstances that his wife had gone to the United States, where, oh, funny story, she dropped dead somehow, who knows, never mind the details, let’s move on. But London Police were not so inclined to dismiss the issue. On July 10, Inspector Walter Dew visited the house, sniffed around for evidence, interviewed Crippen, then left. Though no charges were filed, Crippen was so spooked by the visit that he and Le Neve fled the country the next day.

In their absence, police made a return visit to the home, where, on July 13, they unearthed a grim discovery: a mutilated body, laced with poison, buried under the cellar. Though disfigured to the point of being unrecognizable, the corpse bore an abdominal scar that seemed to correspond to one Belle Elmore had.

Belle Elmore, mysteriously missing wife of Dr. Crippen. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ggbain-05164)

Belle Elmore, mysteriously missing wife of Dr. Crippen. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ggbain-05164)

Inspector Dew was on the case, but Crippen and Le Neve had vanished. We know now that the duo had bolted to Antwerp, where, on July 20, they boarded the SS Montrose, an ocean liner bound for Quebec. And this is where the manhunt began in earnest.

The journey from Antwerp to Quebec took roughly 11 days. By way of disguise, the mustachioed Crippen had shaved, while Le Neve was dressed in drag as his son. But this was not enough to fool Harry Kendall, captain of the SS Montrose. After a few days of seeing this odd pair around the ship, he became convinced that they were the murderous fugitives that Scotland Yard was looking for.

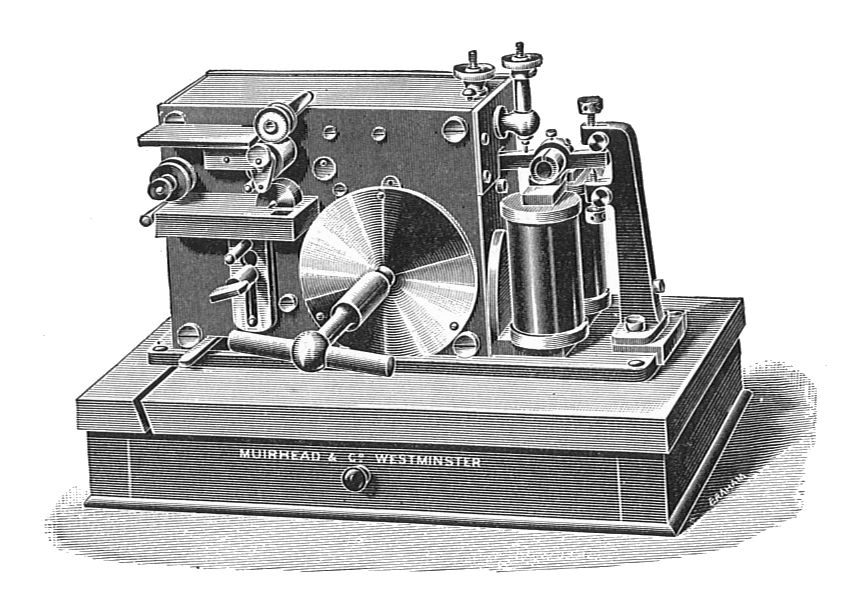

But how to alert the authorities back on land? Fortunately, the SS Montrose was equipped with a wireless telegraph—a marvelous bit of technology Guglielmo Marconi had introduced to the world around 13 years prior. This machine was capable of transmitting Morse code messages over radio waves. On July 24, four days into the liner’s transatlantic voyage, Captain Kendall telegraphed the following message to the White Star shipping office in London:

Have strong suspicions that Crippen—London cellar murderer and accomplice—are amongst saloon passengers. Moustache taken off. Growing beard. Accomplice dressed as boy. Voice manner and build undoubtedly a girl.

At this, Inspector Dew and his crew rallied. In need of a way to reach Quebec before their suspects, they arranged to hop the speedier ocean liner the SS Laurentic. The plan was to arrive in time to intercept the SS Montrose as it chugged along the St. Lawrence River approaching Quebec City, climb aboard, and apprehend Crippen and Le Neve.

The Twitter of 1897: a Muirhead wireless telegraph. (Image: Public Domain)

In the meantime, though, there was still a week left of the SS Montrose’s transatlantic journey. Captain Kendall was eager not to betray his knowledge of the murder suspects to them, or the other passengers. But he had no qualms about sharing the gossip with the media.

He began using the wireless telegraph to send messages to the Montreal Star newspaper, which printed them for the public to read. The details of the wireless missives ranged from the suspense-inducing (“Dr. Crippen has no suspicion that his identity is suspected”) to the mundane (“Miss Le Neve refrains from talking. The pair have no baggage.”)

As the ship’s arrival in Quebec drew near, the Times-Dispatch of Richmond, Virginia, began giving daily updates of the goings-on aboard. Wireless telegraph messages were zinging between the SS Montrose, police forces in Montreal and London, the Associated Press, sources on the ground in Quebec, the SS Laurentic that carried Inspector Dew, and the White Star shipping company, which was just trying to keep track of which of its vessels were transporting accused murderers.

All of this inevitably resulted in some crossed wires and wild, unconfirmed reports. On July 29, a rumor went around that Crippen had killed himself aboard the ship. This assertion, reported in the Times-Dispatch, “caused considerable uneasiness, although it came absolutely without foundation.”

On July 31, the day the Montrose was due in Quebec, the Times-Dispatch printed one last update full of breathless run-on sentences:

To-night the vessel is forcing her way through a storm up the St. Lawrence River, nearing this point, where Inspector Dew, of Scotland Yard, waits impatiently with handcuffs ready to clamber aboard and arrest the man whom he believes to be the American dentist, a fugitive from justice, charged with the murder in London of an unknown woman, thought to have been his actress-wife, Belle Elmore.

The Montrose’s intended disembarkation point was Father Point, a hamlet on St. Lawrence River northeast of Quebec City. In the week since Captain Kendall had, in the words of the Times-Dispatch, “flashed to the world his opinion,” residents of Father Point had been getting increasingly antsy about the ship’s docking. The tense situation was further heightened by the arrival of Inspector Dew, right on schedule on the evening of July 29.

Dew had been tasked with the role of Triumphant Unmasker of the Accused Murderer, and it was a part he couldn’t wait to play. At 8:30 a.m. on July 31, he boarded the Montrose in disguise as a tug boat captain. This was less “improvised Halloween costume” than it sounds—it was customary for tugboat pilots to climb aboard arriving ships to help guide them into port. As a first-class passenger, Crippen was invited to meet the pilots who would, in theory, be guiding him to freedom.

The fugitive stood before Inspector Dew, who, if the legend is true, removed his cap with a cinematic flourish and said, “Good morning, Dr. Crippen. Do you know me? I’m Chief Inspector Dew from Scotland Yard.”

Handcuffs appeared. The jig was up.

Inspector Dew leads the disguised, handcuffed Dr. Crippen off the SS Montrose. (Photo: Public Domain)

The Pittsburgh Headlight reported that at the time of his arrest, Crippen was “broken in spirit, but mentally relieved by the relaxed tension.” Le Neve, by contrast, “sobbed hysterically.” Both were escorted from the SS Montrose and taken back to London to stand trial.

That day, Inspector Dew learned what being at the center of a media frenzy felt like. In a handwritten, 23-page report on his Quebec experience, Dew wrote:

Cameras were thrust in my face and I was practically at their mercy … Fabulous sums were offered me for information and permission to take the photograph of Crippen and especially Le Neve in boys’ clothing.”

The tabloid-style photo-taking continued at Crippen and Le Neve’s trial back in London, when a resourceful reporter managed to sneak a camera into his bowler hat. As court proceedings went on, he held up his hat, aimed the lens through a pre-cut hole, and pressed the shutter button, coughing to cover the sound. This was the resulting news photograph:

Following a five-day trial, Crippen was sentenced to death and hanged on November 23, 1910. Le Neve, tried separately, was acquitted. She left London for the USA on the morning of her lover’s execution.

More than a century later, Britons maintain a perennial fascination with the Crippen case, fueled by its appearance in book, film, and television adaptations over the decades. There is even a waxwork of Dr. Crippen at Madame Tussaud’s Chamber of Horrors in London, where he hangs out with Hitler, Vlad the Impaler, and Genghis Khan.

The perception of Dr. Crippen as a cold-blooded, remorseless murderer, however, has been shaken up in recent years. In 2009, Professor David Foran, director of forensic science at Michigan State University, conducted DNA analysis on the skin of the corpse used as evidence in the Crippen trial. He isolated the mitochondrial DNA and compared it to that of her grandnieces. The results showed that the body was not Belle Elmore’s, as the DNA did not correspond to that of her descendants.

These findings have since been criticized for incorporating wobbly genealogy, so for now the Crippen case remains closed. Regardless of whether the remains used as evidence in the Crippen trial belonged to Elmore, the doctor’s behavior at the time still points toward guilt.

In the hundred-plus years since the dramatic arrest of Dr. Crippen aboard the SS Montrose, in-progress manhunts have gotten increasingly accessible to the public. The Morse code messages that nabbed Dr. Crippen many seem quaint in retrospect when compared to the 2013 search for the Boston bombers that took over Twitter feeds and Reddit threads, but they heralded the modern manhunt—a thrilling chase with an uncertain ending that people can participate in from all over the world.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook