The Most Beautiful Part of a Taiko Drum is Hidden Inside It

The hand-carved drums have intricate patterns concealed within.

The President of Asano Taiko carves the interior of a large nagadō-daiko. (Photo: Asano Taiko)

When Katsuji Asano stretches the fresh cowhide over a coffee-colored lacquered taiko drum, he is performing the last crucial steps in the drum-making process his family has been involved in for 400 years. He is also covering up the most beautiful, intricate part of the drum: the hand-carved patterns lining the interior.

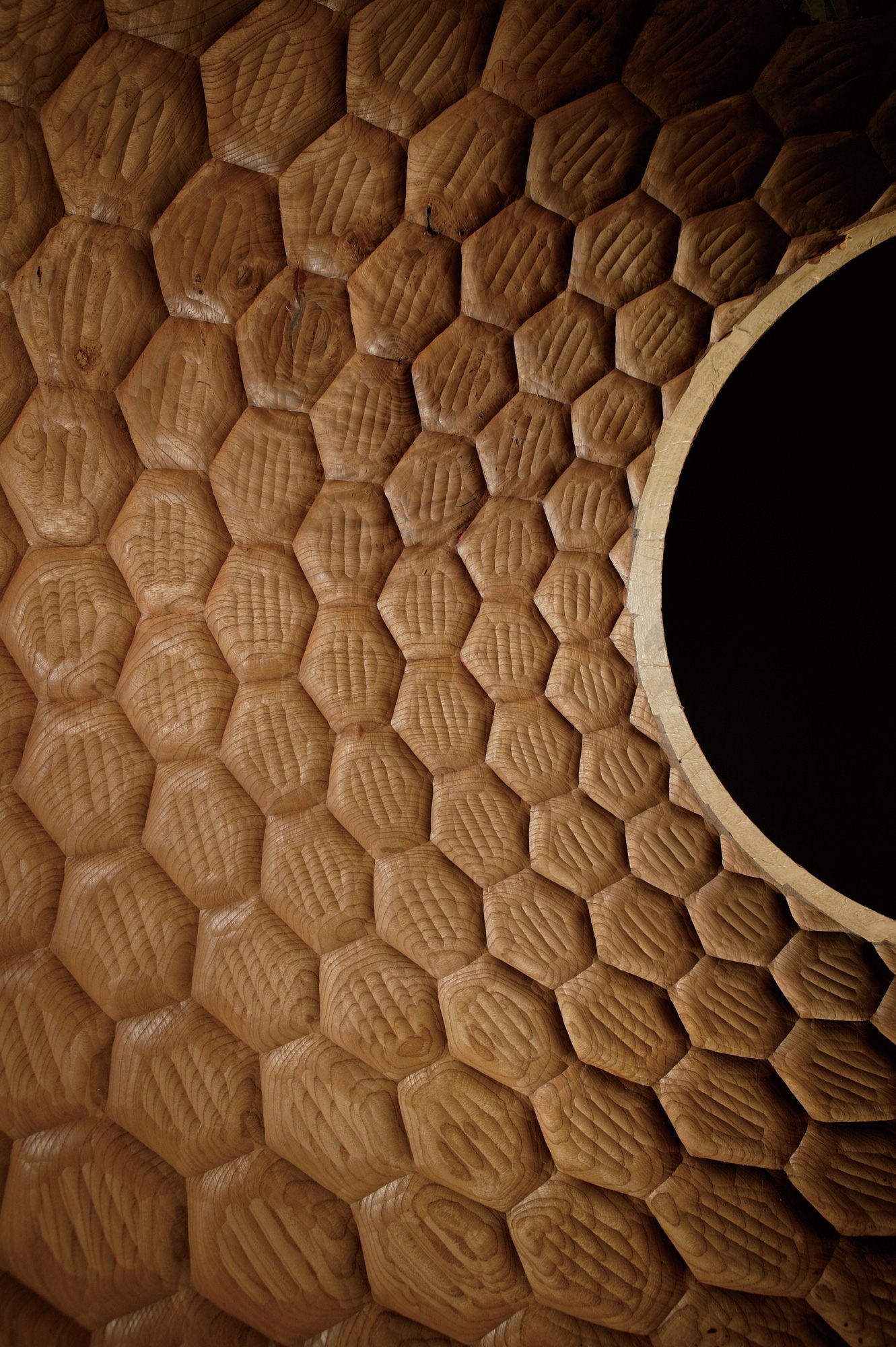

Kikkobori is a type of hexagonal pattern on the interior of some taiko drums. The pattern looks similar to the back of turtle shells. (Photo: Asano Taiko)

Thirty-three-year-old Katsuji comes from a long line of skilled craftspeople or masters of the taiko drum. His family has been running the Asano Taiko factory in Hakusan, Ishikawa Prefecture, since 1609, making it one of the oldest taiko drum manufacturers in Japan.

The taiko (“fat drum”) was initially used in religious ceremonies, at the Imperial Court, and on the battlefield to intimidate enemies and communicate commands. After World War II, local musicians started to implement the drums in festival music and formed taiko drumming ensembles, known as kumi-daiko. Today’s kumi-daiko performances, in Japan and abroad, are known for their exaggerated arm movements, drumstick twirling, and acrobatic leaps.

These performances are compelling, but the process of making the drums has a captivating power all its own.

Asano Taiko craftsman, Mr. Minami, must individually carve each hexagon in the kikkobori pattern. (Photo: Asano Taiko)

At Asano Taiko, the popular barrel-shaped nagadō-daiko is made from an entire tree trunk. Asano Taiko craftspeople begin by felling large Japanese zelkova or keyaki elm trees—chosen for the wood’s density and hardness which gives taiko its particular tone. (Drums that aren’t made out of keyaki often have a bell-like, sharp echo.) The whole tree is hollowed out and curved into the barrel shape before the wood is aged in a temperature-controlled, low-humidity warehouse. Depending on the type and size, drums need to be aged for two to three years.

After the wood has been aged, exteriors are further shaped and thinned down with handtools before the inner shell is decorated with ornate and precise patterns. These little additions make all the difference, not just aesthetically, but in their effect on the resonance and timbre of the drum.

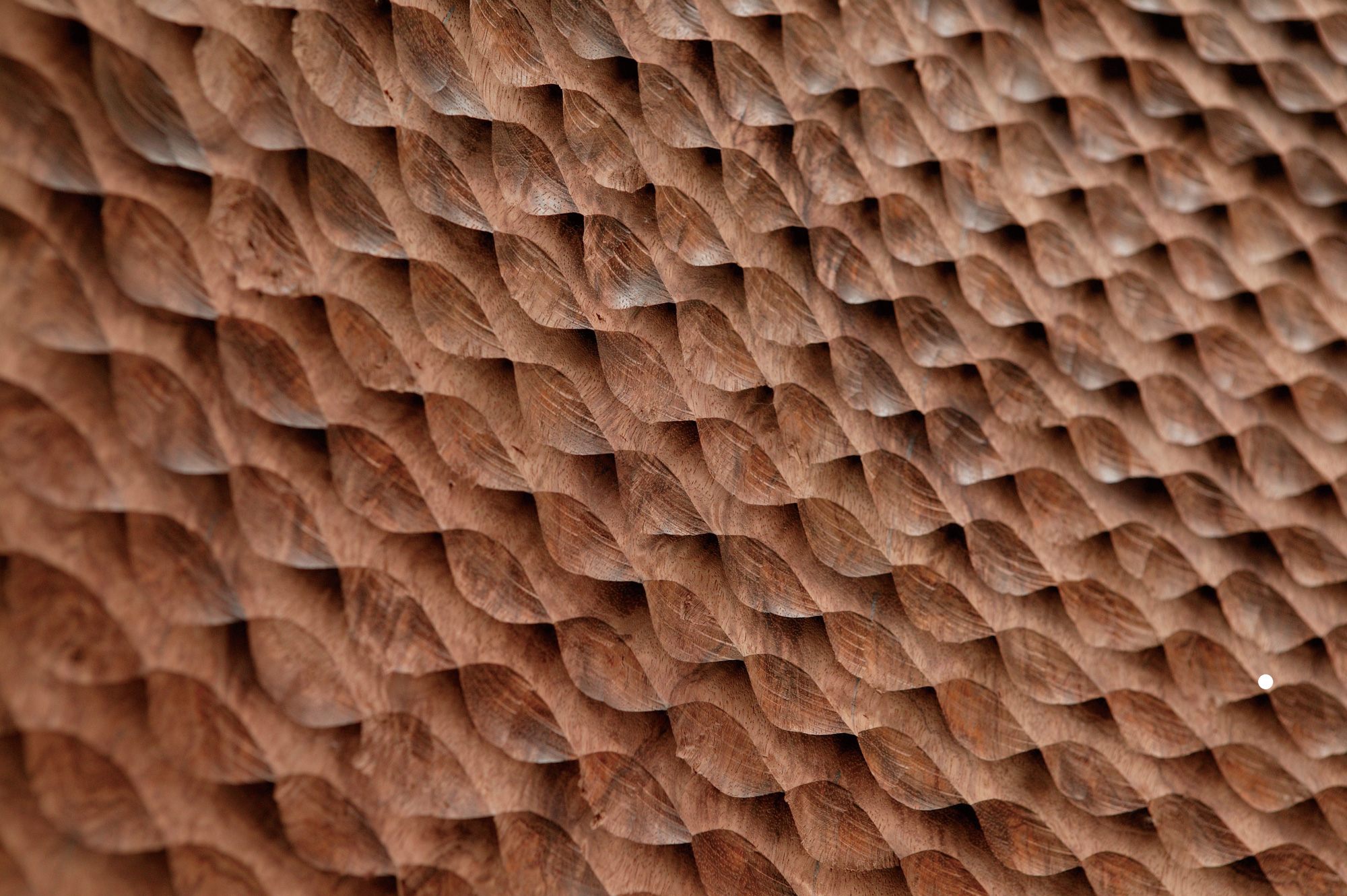

The rows of the six-sided pattern, amijyourokobori, look similar to fish scales. (Photo: Asano Taiko)

“There are different shapes that the craftspeople are skilled at and have a sense of how each of them affects the tone,” Katsuji says. “They pick one of them for the purpose of making the body sound a specific way.” Asano Taiko commonly uses these four patterns: tight zig-zags (yarigataayabori), six-sided turtle back (kikkobori), fish scale (amijyourokobori), and tornado (hadosenjyobori). Some interiors of special odaiko drums are covered in gold to improve resonance and clarity.

The zig-zagged lines of the yarigataayabori pattern. (Photo: Asano Taiko).

When taiko came to the United States, the earliest kumi-daiko groups who couldn’t afford to import drums from Japan used old drums they found in local Buddhist temples or improvised with crude materials, such as oak wine barrels. White oak can make the drums sound a little too sharp, explains Mark Miyoshi, the owner and principal craftsman at Miyoshi Daiko in Mount Shasta, California. “That’s one of the reasons why you need to do the carving on the inside. With the right kind of carving you can kind of negate the high-pitch ringing sound that can come out of the barrel.”

Miyoshi working on the interior of the 40-inch odaiko that took him about six weeks to complete. (Photo: Mark Miyoshi/Miyoshi Daiko)

Miyoshi learned the basic drum-making skills from the San Jose Taiko group, but further refined the wine barrel method into a sophisticated alternative to the original Japanese process. In 1989, he received a fellowship to learn how taiko drums are made in Japan, and found that a lot of his own methods were the same, including the carving patterns in the interior of the drum.

The tornado, spiral pattern, hadosenjyobori. (Photo: Asano Taiko)

The finishing touches are some of the most critical steps in getting the drums to sound correct. Once a coat of lacquer is applied to the exterior, wet cowhide is laid out over the head of the drum and the edges are tied taught with ropes laced around a series of wooden pegs. Determining how tightly and how far to stretch the skin is a decision that could alter the entire tone of the instrument.

Mark Miyoshi sews the hide on a 46-inch okedo head. (Photo: Mark Miyoshi/Miyoshi Daiko)

In these last steps of the taiko making process, Katsuji at Asano Taiko channels the training and advice passed down from his father. “Imagine the player playing the instrument,” Katsuji says. “Imagine the sticks or the bachi that they’re using and the strike. Ask yourself if that is the right tone, if that’s the right tension for that particular drum.”

Katsuji is now spearheading Asano Taiko U.S. in Torrance, California, which handles taiko repair and sales in the United States as well as taiko drum playing classes. He was officially employed three years ago, but grew up around the factory in Japan observing the making process, getting his hands on taiko drums when he could, and learning from his father who is one of the executives of the company. He hopes to share the vibrant taiko culture to the United States and international players.

A 40-inch odaiko created by craftsman Mark Miyoshi on display at the Musical Instrument Museum in Phoenix, Arizona. (Photo: Mark Miyoshi/Miyoshi Daiko)

The distinct sound of the taiko comes from using all natural elements and skilled craftsmanship. Katsuji says it’s this sound that resonates naturally with musicians around the world.

“It’s a very specialized and highly developed art form,” says Miyoshi, who inscribes a dedication or prayer in addition to the unique patterns decorating the interior of the drum. “When it’s played, I feel like the music will carry that dedication out to the rest of the world.”

Katsuji Asano’s interview was translated with the assistance of Kristofer Bergstrom.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook