The Mystery of Why Chattanooga Raised Its Downtown by a Level

There’s a hidden layer of Chattanooga underneath the current city.

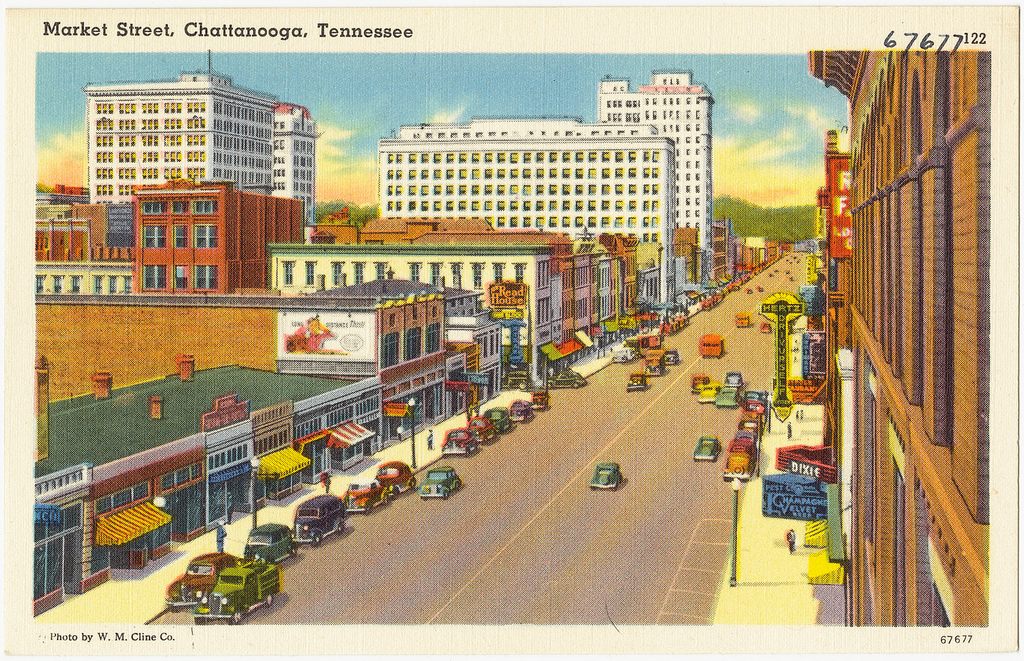

Walk the streets of downtown Chattanooga, Tennessee, today and you’ll find little evidence that the town’s residents of yesteryear conducted business in first floors that are now below sidewalks and parking meters. For that, you have to go underground.

“So this is Loveman’s,” says Cheri Lisle-Brown, property manager for the 130-year-old Loveman’s Building, which was originally a department store, in the heart of Chattanooga’s downtown. She walks through a pair of metal doors. “This is the original freight elevator. Watch your step.”

Below, the basement of the 19th-century building is made from a mix of cinderblock, brick walls and Tennessee limestone. It has the feel and smells of other old basements. Unlike other basements, however, the northern outer wall has openings in the brick—doorways or large windows—framed with wood leading to an alcove. What looks like a place to enter the building or let in light sits underground.

At some point in time, possibly between 1875 and 1905, Chattanooga built up its roads and abandoned the first stories of the buildings in the downtown of the city, turning them into basements. Today, no one knows exactly why or how it happened. The popular theory is that Chattanooga raised its city a story to escape the devastating flooding the Tennessee River wrought every few years. Evidence also points to an attempt to escape the diseases of the day, cholera and yellow fever.

Cities build upon themselves. For example, they pave over cobblestones that were once dirt paths. For Chattanooga, located a few miles from the Tennessee-Georgia state line, the foundations of the buildings echo the story of a construction project more unusual than most.

The best proof of Chattanooga’s hidden layer can be found in the basements of its older buildings. Yet the city’s original first floor is largely off limits to the curious because the locations are on private property.

And there’s the mystery of it. Documentation of the construction is scarce. City records don’t point to any motion where city leaders resolved to raise the streets. Newspapers from the time discuss the proposal but did little to document the earth moving project. This leaves modern city historians unable to answer basic questions like “when did this occur?” and “where did the city get the soil?”

“It required concerted effort—and that’s the big question mark—because there’s not a lot of evidence for it,” says Nick Honerkamp, professor of Anthropology at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, of the massive infrastructure project.

Indeed, utility workers would occasionally find items like a cut tree trunk eight feet below ground, he notes. Honerkamp’s predecessor, Jeff Brown, first posited the theory that the city initiated a project that raised the streets and made first stories basements after he noticed the doors and windows in basements of Chattanooga’s downtown. “It doesn’t make sense to have a window or a door that leads to dirt,” Honerkamp says.

As part of this theory, some people think that the dirt excavated from the Hamilton County Courthouse was pushed downslope to fill the streets below. The building, according to Honerkamp, features a large basement. “That dirt had to go somewhere and the easiest place to put it was downhill,” he says. The file the Chattanooga Public Library keeps on the project suggests the soil might have been lifted from one of the nearby hills.

Braving floods was a risk of doing business in Chattanooga during the 1800s and early 1900s. “We had dramatic floods virtually every decade,” says Maury Nicely, a Chattanooga-based lawyer and amateur historian. Chattanooga made its fortunes from the railroad system connecting it to the rest of the South and the Tennessee River. The main streets running from train depot to river were “low-lying troughs” that filled during large floods, according to Nicely.

Ultimately, it was a problem that was solved in 1933 when the U.S. Government created the Tennessee Valley Authority, which built hydroelectric dams along the river and stymied the floods.

But in 1875, city leaders were wrestling with what to do after flood waters once again ripped through their town. Robert Hooks, the city’s engineer, floated the ideas of building a levee and raising the streets in the March 4 edition of the Chattanooga Times. “The streets of Chicago, Boston, and many other cities have been raised, both for the purpose of escaping flood and for improving their system of sewerage,” Hooks wrote.

That week, Chattanooga’s Board of Mayor and Alderman considered a proposal to raise 15 miles of street 10 feet high, paid for by the property owners, but the resolution was put off. As Hooks noted earlier, these projects were cost prohibitive.

More motivation arrived in the summer of 1878, when yellow fever spread across the Mississippi River basin, striking its victims with jaundiced skin and black vomit, and killing thousands. In Chattanooga, 140 people in the city of 12,000 died.

People at the time didn’t know the true carrier of the disease, Aedes Aegypti mosquitoes, which can spread the Zika virus of today. But Chattanooga’s then-Registrar of Vital Statistics, J. H. Vandeman, was onto something when he wrote: “The more filth, the more yellow fever; the lower the ground, the poorer the drainage and water supply, there you would find this disease the worst.”

In 1878, people were already trying to raise up the land in downtown Chattanooga, but it was going in fits and starts. During his postmortem of how yellow fever infected the city, Vandeman described how even in the city’s downtown the ground never completely dried. He pointed out one building in particular, which is today known as the Loveman’s Building.

The building had been recently built with a commercial first story below the level of the street. It was not a good place to do business, however. It “is constantly exposed to dampness of the soil underneath, amounting at times to large collections of water,” Vandeman wrote.

The lot 100 feet to the east was not helping, either. The developer there placed fill so that the lot stood three feet taller than the ground of the Loveman’s Building. This cut off drainage. In other words, people were filling up Chattanooga a little at a time. Those who did not do so were left with damp ground.

As a result of the epidemic, Vandeman called for the city to improve its sanitation. Build out the sewer system, he wrote, and “increase our surface drainage.”

Unlike a city such as Paris, with its maze of catacombs and sewers, Chattanooga’s underground is mostly contained to a dozen or so basements today. Other basements were never first-story floors because they were dug out at a later date. “It’s a lot more localized than most people think,” Nicely says.

As with many places in cities, unused spaces are not long left unused. Today, a portion of the Loveman’s Building is used as storage for the current tenants of the building. Before she had the basement sealed, “I used to get a lot of flooding,” says Lisle-Brown, who managed the property for 10 years.

This is part of the nature of cities: they change and adapt to challenges, says Honerkamp. Sometimes it’s subtle, other times it’s dramatic. “To me, it represents a corporate, combined effort—between city and private individuals—to address a basically pretty horrific problem that was messing up the economy and driving people crazy.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook