The Once Glamorous Salton Sea is Now Rife With Toxic Dust and Dying Fish

The Salton Sea is a polluted accident turned natural resource, and the government is finally giving it funding.

Abandoned pier on the Salton Sea, California. (Photo: Hank Shiffman/shutterstock.com)

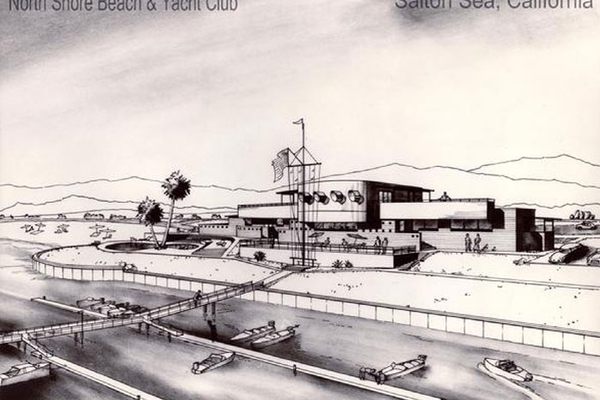

In the Imperial Valley of California’s southeastern desert is an unexpected, almost oasis-like sight: a vast saline body of water called the Salton Sea, covering an area of around 350 square miles. On a closer look, though, its long-term neglect is obvious. The area, once called the “California Riviera”, was once awash in pastel boating outfits and jet skis; now it’s littered with broken trailers and run-down yacht clubs. Millions of fish die there yearly, largely from the water’s rampant avian botulism.

And now, decades after the water began to recede into an ultra-concentrated smelly, salty mess, environmental groups are finally getting funding to manage the water. “It’s a terminal lake, which means there are no outlets to the Salton Sea,” says Bruce Wilcox of the California Natural Resources Agency, part of the Salton Sea Task Force. “Anything that’s in the water or comes into that basin stays there, and it’s getting progressively saltier.”

The Salton Sea is now one-and-a-half times saltier than the ocean, and evaporating quickly. But saving the Salton Sea isn’t your typical restoration effort, undoing human mistakes. This time, ecological interest groups are fighting nature to keep the mistake intact: the Salton Sea is a man-made lake, created by accident.

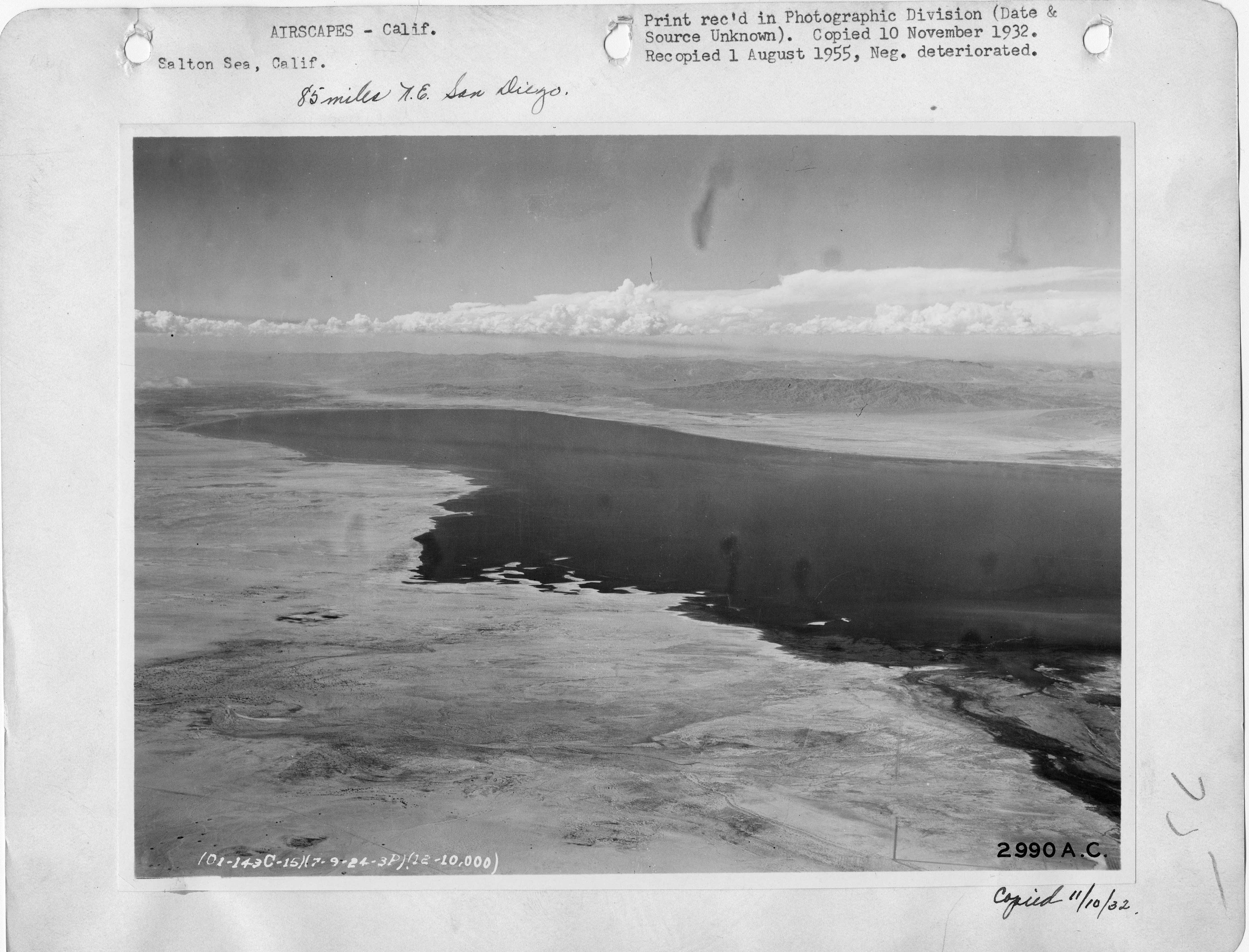

An aerial view from the early 1930s of Salton Sea. (Photo: National Archives/23935069)

“The fact that [the Salton Sea] was an accident, and a human accident, makes no difference to the birds,” says Wilcox. Birds use the Salton Sea as if it were a natural habitat, and taking that away would cause more damage than it would have decades ago; most of the wetlands along the shores and central valley of California have since been drained and developed. Losing the Salton Sea would be destroying a necessary foodsource and pitstop for thousands of birds migrating from the west, Appalachia and Colorado, many of which would face extinction, unable to replace the loss.

This is an unexpected development for the Salton Sea, considering that for much of its history, it wasn’t a source of water at all. In 1900 the Salton Sea was called the Salton Sink, and was, at the time, a dry geological depression, deep and wide, with vast salty deposits on its floor. Commercial interests grew around it: salt farmers harvested the basin, and the California Development Company began an irrigation project to send water from the Colorado River to surrounding farmland, which exists today. The company dug canals to divert water into the Coachella and Imperial Valleys, hoping to build lush green farmland in the desert.

Unfortunately, a series of mishaps plagued the area from the beginning; the Colorado River was not yet controlled by the Hoover Dam, and the canals flooded and filled with silt. Efforts to fix the problem included making additional, hasty cuts into the river basin, making the problem worse, and money and interest ran out after a major flood filled the Salton Sink at a rate of one inch per hour. For two years, the Colorado River filled the sink creating a large saline lake, later known as the Salton Sea.

Old signage at Salton Sea. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-highsm-21008)

Over time the Salton Sea became a tourist draw. In the 1920s its soft waves and migrating birds enchanted entrepreneur Gus Eilers into promoting the area and building a clubhouse with boat races near the water. The word spread, and property developers rushed to the area, building marinas, resorts, and a yacht club in Salton City—the Salton Sea became known as the California Riviera. In June 1954 women entered an annual contest to become the official Miss Salton Sea.

Celebrities like Frank Sinatra and Jerry Lee Lewis spent their weekends boating and jet skiing into the 1960s, and fish were added to the brackish water for recreation. Corvina and tilapia thrived, attracting birds and fishermen to the new watering hole. But, since the Colorado River was under control, its water wasn’t supplying the desert sea with water anymore; farming continued to thrive in the area with more controlled irrigation, and unregulated agricultural runoff began to flow into the lake from nearby farms, sustaining its water levels to a degree.

The Salton Sea had been slowly shrinking since the 1950s, but hurricanes in 1976 and 1977 further devastated the area. Conservation groups sought aid from the government. Sonny Bono (of Sonny and Cher fame), who by the 1980s was a congressman, introduced plans to save the Salton Sea before his death. The plans were briefly supported before falling by the wayside, though a wildlife refuge there bears his name. As the water and property values evaporated, many people moved away, and the area faded from public consciousness.

Abandoned gas station at Salton Sea. (Photo: Marc Cooper/Public Domain)

Now, the Salton Sea is surrounded by vacant property and few residents remain beyond a smattering of elderly folks and families attracted by the low cost of rent. Fish have been dying by the millions since the 1990s. The water is now at 59.3 parts of salt per thousand parts water, and “fish can’t breed at 60 parts per thousand,” says Wilcox, though invertebrates continue to thrive. Locals complain of the smell, the lack of stores and amenities, and the regret that their property investments did not live up to the dream.

But the issues around the Salton Sea are getting more serious, beyond the financial collapse of a local tourist economy. On Monday, there were 200 earthquakes under the lake, which sits near several fault lines including the San Andreas Fault. Water management in the region is an issue in the desert and for California, which had to divert water from reaching the Salton Sea in 2003 in order to supply San Diego. A 2014 report estimates that by 2045, the receding lake will expose nearly 150 miles of the lake’s floor, called “playa,” which will release around 100 tons of fine dust into the air per day.

“The playa is hazardous because it’s such a small size dust particle,” says Wilcox. “They can travel through your lungs into the bloodstream.” The surrounding valleys provide much of the United States’ produce, and that dust will also destroy crops, affecting our food supply. Since 2003 elevation has dropped six to seven vertical feet, exposing 10,000 to 11,000 acres of playa around the lake, which would flood the area and the Coachella Valley to the north with dust.

A ditch in the Salton Sea. (Photo: Akos Kokai/CC BY 2.0)

Current playa control plans of the Salton Sea Task Force include finding areas that are higher in arsenic and copper, in order to control those first, with an initial goal of 12,000 acres of habitat creation and control. Teams will build canals and storage ponds next to the Alamo and New rivers to store agricultural runoff to add water to the lake. Plans also include rooting the playa with plants, covering the dusty Salton Sea floor, and building nearby shallow habitat wells for fish and insects while monitoring the lake’s salinity. Wilcox adds that wildlife concerns are pressing: the Salton Sea alone is a vital stopover point for over 420 species of birds.

While these matters are in need of immediate action, those who are working on and advocating for saving the Salton Sea are realistic; they’ve stopped calling their efforts “restoration,” and instead use the word “management.” “What we’re talking about doing will not turn it into a natural habitat, it will have to be managed forever,” says Wilcox. “But we’re trying to put something in place that has minimal management requirements over time.”

While the task force’s plans are not entirely funded, the California government recently earmarked 80 million dollars for saving the water, which is a start. President Obama’s administration gave another $30 million from the federal budget in September of this year. In addition to suppressing the playa and adding water, Wilcox says these plans aim to add value for humans and local tourism. Bird watchers and sailors may one day use the Salton Sea again, though the waters will never be quite as deep as they were before.

Dead fish on the sand at Bombay Beach. (Photo: EsotericSapience/CC BY 2.0)

A new full proposal with updated cost estimates and data is scheduled for release at the end of 2016, just before the last holdout of water supplying the basin will be removed per agreement the following year; implementation of many management plans is estimated to begin next year. While some plans are estimated to cost millions of dollars, the alternative—which includes a major public health hazard—could cost the government over $70 billion if it spirals out of control.

The Salton Sea was made through blunders because of human desires, but over time, those actions actually made the large salty lake vital. Hopefully a new course of human intervention for it will arrive in time to sustain our lucky mistake.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook