The Oscar for Best Forgotten Film Pioneer Goes to this Black Director

Oscar Micheaux c. 1913. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Who was the most prolific African American filmmaker of the silent film era? That’s a question that undoubtedly has some asking, “were there any?” Absolutely. The Jim Crow era’s effect on filmmaking is rarely discussed outside of film history circles, leaving one of its most prominent figures, Oscar Micheaux, largely forgotten.

Oscar Micheaux was a pioneer in almost every aspect of film, but before that he was a determined boy from southern Illinois. Born in Metropolis, Illinois, in 1883, Micheaux was the first generation of his family born free in America. The importance of property ownership and education was instilled in him during childhood.

After a stint as a Pullman porter in Chicago, where he saved a great deal of money, Micheaux moved to South Dakota so he could own his own land and write. His first novel, The Conquest, was self published in 1913. He wrote two more novels before setting his sights on the film industry. The self-taught writer left his South Dakota farm and moved to Chicago, where he started the Micheaux Film and Book Company.

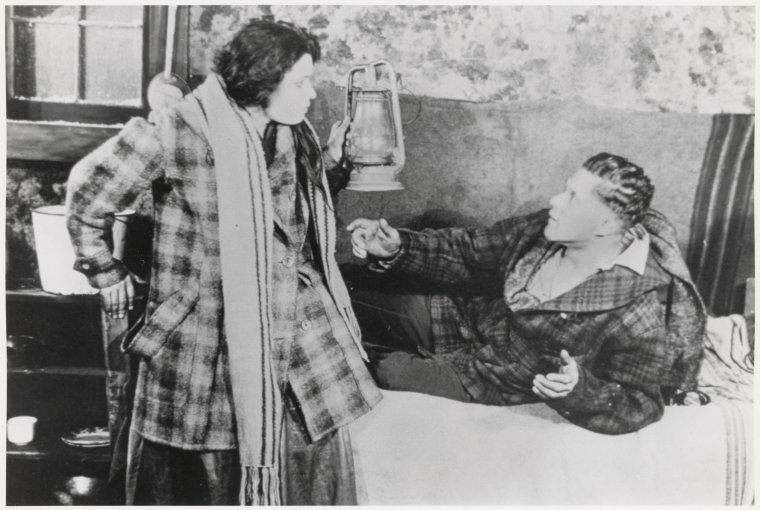

Iris Hall and Charles Lucas in a scene from Micheaux’s film The Homesteader. (Photo: Public Domain/New York Public Library)

His first film was an adaptation of his novel, The Homesteader, about a black homesteader in the Dakotas who falls in love with the daughter of a Scottish widower. In 1919, Micheaux raised the money on his own to film and produce The Homesteader in Chicago, becoming the first African American to make a feature film.

Context is important for how incredible this venture into film is. Micheaux’s silent film, about a forbidden seemingly interracial romance (the female love interest does not realize she is not white) that is ultimately ill-fated, would have been ground-breaking even had it not had the distinction of being the first black-helmed film to be classified as a feature. The film industry was just beginning and while Hollywood was the biggest player, there were independent film companies throughout the country. Chicago was the Hollywood of “race films”–movies produced for an all-black audience–and black filmmakers owned production companies throughout the city.

The film industry in its early days (and for decades later) was not kind to other races. African Americans were cast on screen in offensively stereotypical caricatures or subservient roles. This is why race films were revolutionary in their portrayals of non-whites as real people with their own joys and struggles. The term “race film” probably sounds racist and exclusionary by today’s standards, but in a time ripe with racial segregation, it was a necessity for blacks to see their stories on screen, and this was the only way to see them. Sadly, very few of these films were preserved for posterity. Most of them, including The Homesteader, have been lost.

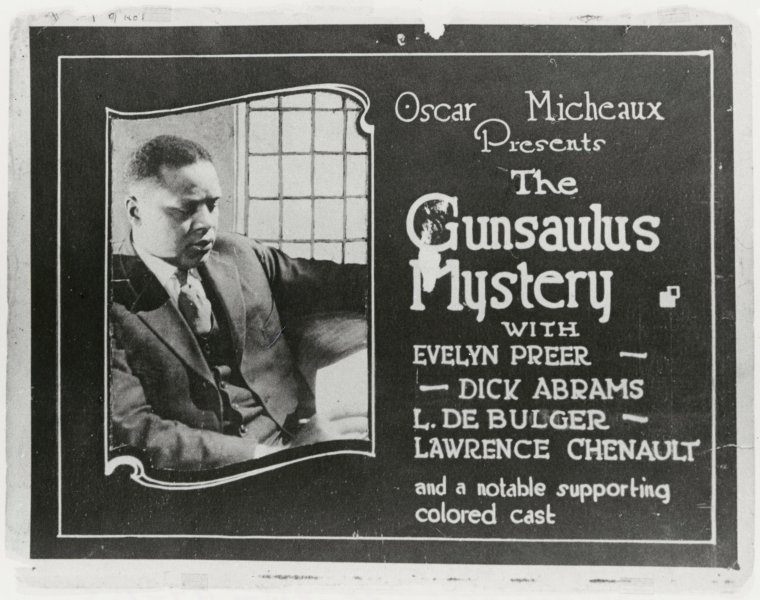

Lobby card for Micheaux’s 1921 film The Gunsaulus Mystery. (Photo: Public Domain/New York Public Library)

As a genre, race films existed from the silent era until 1948 when United States v Paramount Pictures put an end to the studio system and allowed more distribution for independent filmmakers. It is estimated that around 500 race films were made in all.

This is all to say that there was a direct market for Micheaux. His films were played in black urban neighborhoods throughout the country. His most celebrated film is the 1920 silent feature Within Our Gates. Within Our Gates was a response to the D.W. Griffith’s racist epic Birth of a Nation. While Birth of a Nation depicted the Ku Klux Klan as heroic, Micheaux made a film that showed African Americans as heroes in the face of racism. Within Our Gates dealt with threats of lynching, Ku Klux Klan revivalism, and whites’ fear of blacks in their communities. It shone a light on what we would probably consider to be the prevailing racism and racial struggle of African Americans for the entire next century. And it was the first to do so.

Not one to rest on his laurels, Micheaux continued working intensely for the next three decades. He went on to make over 40 movies, continuing to push buttons in the African American community. He was the first black filmmaker to make a talkie with 1931’s The Exile. With 1948’s Betrayal, he became the first black filmmaker whose work was shown to white audiences. It was his final film. He died a few years after its release, while on a promotional tour in 1951.

A scene from Within Our Gates, Micheaux’s 1920 film. (Photo: The Riverbends Channel/YouTube)

With all of these accomplishments, how is it that the majority of the public has never heard of Micheaux before? Why isn’t he celebrated alongside early filmmakers like Charlie Chaplin or Cecil B. De Mille?

Maybe because he wasn’t a very good filmmaker.

Critics, both modern and of his time, have pointed out that Micheaux was not all that technically skilled. Most of his films are lost, as most old silent films are, but those that remain are filled with camp and melodramatic scenes riddled with shoddy editing and continuity issues. What makes him worth talking about, however, are the themes in his films. His themes of interracial marriage, lynching, and voting rights during the Jim Crow era of segregation make him a champion of early African American filmmaking–regardless of his technical skill.

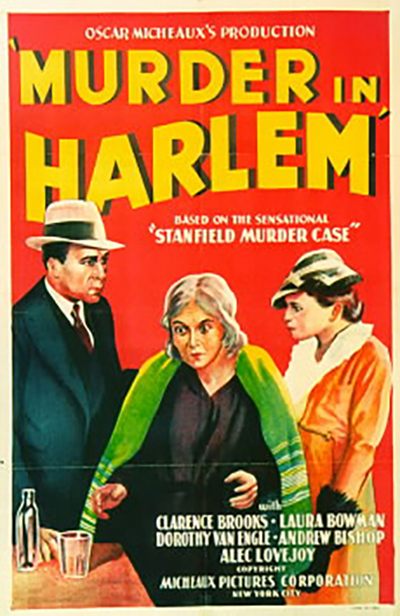

The Gunsaulus Mystery was remade with sound in 1935 as Murder in Harlem. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

A lot of the reason for his poor filmmaking, however, was a looming threat of bankruptcy. The director would famously ignore actors’ requests for retakes and technical issues that arose during shooting. However, others contend that when he did find the money, Micheaux’s work was focused and detail-oriented. The criticism that he was a poor filmmaker can perhaps be explained by the fact that he was literally poor.

Similarly, the Harlem Renaissance generation didn’t pay him much due at the time either. They looked down on Micheaux. They were middle class and educated. He wasn’t. Critics at the time, as well as his contemporaries, often lambasted his efforts. He was always either doing too much or too little. Black critics have pointed out that he presents unattainable ideals for black people, with most of his characters being light-skinned and wealthy. Micheaux saw it differently. He thought he was inspiring people. He thought he was challenging what it meant to be black in America and stirring up conversations about black identity.

Still, it’s hard to discredit the work of such a prolific African American filmmaker at a time when black expression was not readily seen. When cinema was taking its first teetering steps, this ambitious former farmer turned himself into an author, director, producer whose films recognized the concerns of a long-disenfranchised group on the silver screen.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook