The Poisonous Beauty Advice Columns of Victorian England

A woman applies lipstick in Joseph Caraud’s La Toilette, 1858. (Photo: Public Domain/The Athenaeum)

Glass and tin bottles hide snug in a case, waiting for a woman’s daily ritual. She reaches for a bottle of ammonia and washes it over her face, careful to replace the delicate glass stopper. Next, she dips her fingertips into the creams and powders of her toilet table, gravitating toward a bright white paint, filled with lead, which she delicately paints over her features. It’s important to avoid smiling; the paint will set, and any emotion will make it unattractively crack.

In Victorian England, these were some of the ways women began their daily beauty routines. Unfortunately, cosmetics of the era were plagued by caustic chemicals that could also cause bodily addiction. And, similar to today, the advice on how, if, and when to use these treatments came from the era’s most popular beauty columns.

One such column, from Harper’s Bazaar, was called “The Ugly Girl Papers: Or, Hints for the Toilet.” It was written by a Mrs. S.D. Powers, a beauty expert of the time, and became so popular that it was re-published in 1874 as an anthology. The “Ugly Girl Papers” has the tone of a wise aunt with endless advice on how to solve your beauty woes.

In one chapter Powers asks, “Is there such a being as a hopelessly homely woman?” It is a rhetorical question, and readers of the time would have known the author’s firm belief that one could go from average to “charming” with just a few dress and makeup adjustments. Powers prized subtlety in makeup, though, and always included careful reminders to be sparse with powder and rouge.

According to Powers, women’s beauty was an elaborate, skilled, and semi-secret performance. “Everybody knows they are inventions, and accepts them as such, like paste brilliants at a theatre,” she wrote.

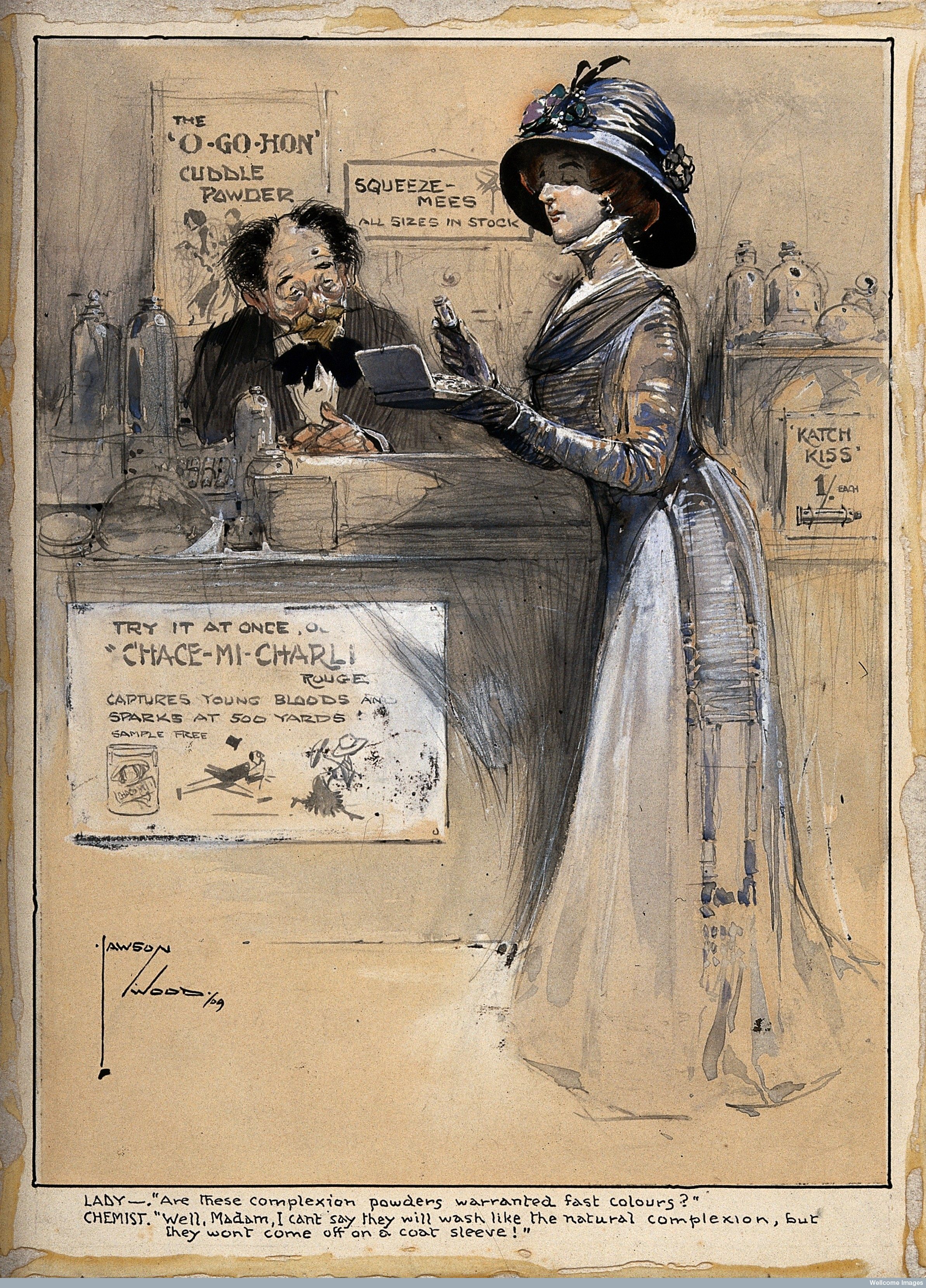

A woman queries the durability of cosmetics at a pharmacy. (Photo: Wellcome Images, London)

Victorian beauty ideals were unsurprisingly obsessed with pallor: upper class white women chased even whiter skin, a symbol that their privilege never left them working in the sun. “It was all about how to make your skin more translucent,” says Alexis Karl, a perfumer and lecturer who has researched Victorian cosmetics extensively.

There were two dominant makeup styles in the 1800s: “natural” and “painted.” The ideals of “natural” skin care conjured images of the “English Rose”; a wholesomely beautiful woman with good morals, but Karl notes “it was understood that there was a lot of artifice going on.” The “painted” beauty regime was seen as a bit risqué; these women were not hiding their artifice nor their desire to be beautiful.

Similar to the “no-makeup makeup” trend that exists today, the natural look was often achieved through unnatural preparations, many of them homemade. Modern beauty practices belie the roots of current ideals: a chemical called Taraxacum is suggested as a sort of 1800s chemical peel by Powers, who says “the compress acts like a mild but imperceptible blister, and leaves a new skin, soft as an infant’s.”

To keep the face fresh, she advises coating the face with opium overnight, followed by a brisk wash of ammonia in the morning. For the woman with sparse eyebrows and eyelashes, mercury was often recommended as a nightly eye treatment, eradicating the need to use heavy makeup. “The look of the consumptive was very desirable: the woman with the watery eyes and pale skin, which of course was from the cadaver in the throes of death,” says Karl.

An 1898 advertisement for Dr. Campbell’s Safe Arsenic Complexion Wafers. (Photo: Jussi/flickr)

To get this near-death look, women would squeeze a few drops citrus juice or perfume into their eyes, or reach for some belladonna drops, which lasted longer, but also caused blindness. Pale skin was encouraged with veils, gloves and parasols, but could also be bought: Sears & Roebuck sold a popular product called Dr. Rose’s Arsenic Complexion Wafers, which were just that–little white chalk wafers filled with arsenic for delicate nibbling. They were specifically advertised as “perfectly harmless.”

Arsenic, a natural metalloid found in the earth’s crust, is an extremely toxic compound that can be tolerated for a time when eaten in small amounts (and has occasionally been used in medicine). Long-term exposure, however, is extremely unpleasant: nervous system and kidney damage, hair loss, conjunctivitis and growths called arsenical keratoses plague the body along with, yes, vitiligo, which causes pigment loss in the skin. Arsenic, which became addictive as a person’s tolerance built, was used in as many forms as possible.

Lola Montez, a Victorian actress and traveling beauty writer, wrote in her book The Arts of Beauty about how women in Bohemia (now a part of the Czech Republic) regularly bathed in arsenic springs, “which gave their skins a transparent whiteness.” She also warned of the price: “once they habituate themselves to the practice, they are obliged to keep it up the rest of their days, or death would speedily follow.”

Though beauty-related deaths were not always reported as arsenic poisoning, it wasn’t that Victorian women didn’t know arsenic was toxic or addictive. It was not uncommon for it to be used as a poison by murderesses of the era, and by the late 1800s arsenic was known to be a dangerous ingredient when used in dyes and wallpaper. The use of arsenic in small quantities for skin lightening was considered so effective that it continued for decades.

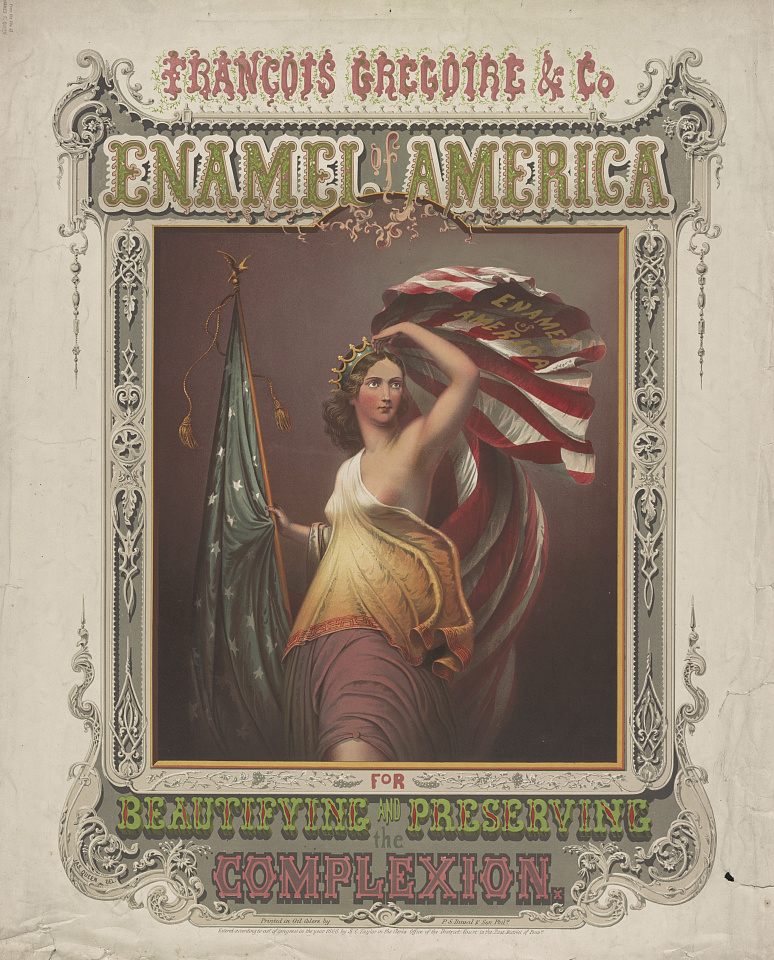

An advertisement from 1847, for François Gregoire & Co’s “Enamel of America for beautifying and preserving the complexion”. (Photo: Library of Congress)

The mentality associated with using dangerous substances was possibly rooted in the era’s culture. ”Toxicity is one thing, but there was also a stream of mortality running through daily life,” says Karl. Victorian life was full of everyday dangers beyond poisoned products; diseases, fires and electrical mishaps may have contributed to an obsession with death that made domestic dangers, like skin care, easier to overlook.

While the skin remedies geared toward a “natural” look were dangerous, the painted ladies were hardly better off. Women who used these products coated their faces and arms with white paints and enamels, in an effort to cover their natural skin tone and mimic an extremely pale complexion. These products were made from lead, which is corrosive–the more paint you wore, the more you needed to wear next time to cover your damaged skin. Vermillion, sometimes called “red mercury”, was a known poison and lip tint.

Many advice columnists, including Montez, vehemently hated enameling. “If Satan has ever had any direct agency in inducing woman to spoil or deform her own beauty, it must have been in tempting her to use paints and enameling,” Montez declared.

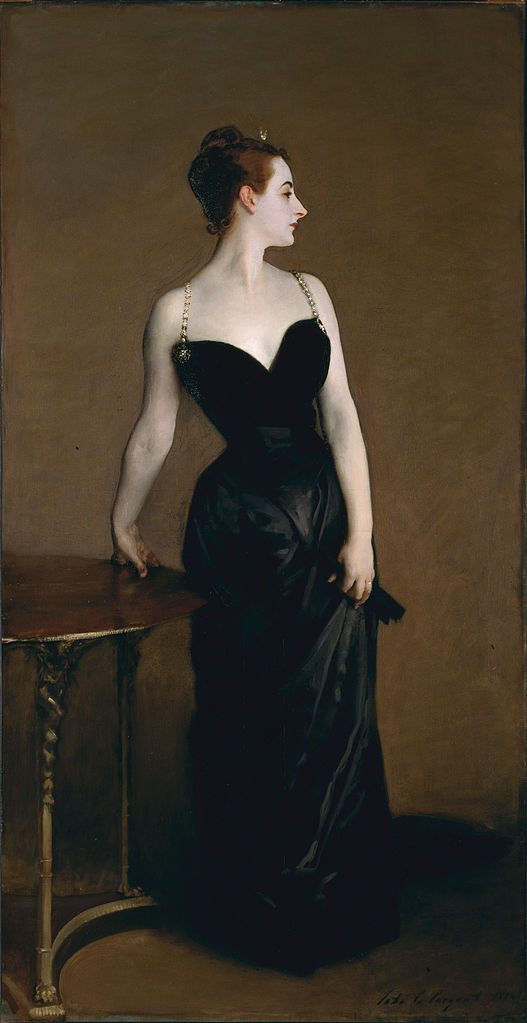

John Singer Sargeant’s painting Madame X. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

One painted woman, Virginie Gautreau, depicted in a black dress in Sargent’s famous portrait “Madame X”, was admired and hated for the sensualization of her corpse-like skin. “Madame X would use indigo dye to paint veins on her arms, over the enamel. She was highly skilled–these women were literally living pieces of art,” says Karl.

While wearing the enamel, painted women had to keep a largely emotionless face, against the risk that the enamel would crack. According to Karl, they made a concerted decision to paint rather than employ “natural” cosmetics methods, which were used out of sight and at home. Once you began to paint, everyone knew you did so, and in a social sense you could never switch to a natural look.

When read as a collection, beauty columns like “The Ugly Girl Papers” have a strangely contradictory feel. In one instance, Powers claims that “ammonia is the most healthful and efficient stimulus for the hair” and in another insists that to remove unwanted hair, all that is needed is a good application of ammonia.

The frontispiece for The Ugly Girl Papers: Or, Hints for the Toilet. (Photo: Internet Archive)

Youthful grace was emphasized, until Powers herself aged, when she began talking of the beauty found in grey hair. There is a surprising amount of advice that seems comparable to beauty and health columns of today, including eating well, keeping fit, and developing mental health and a sense of self-worth. At the same time, none of the above were optional lifestyle choices in the eyes of many beauty mavens at the time: the word “duty” comes up in these columns a lot.

Today’s consumers like to think they are savvier than the Victorians, of course, and there have indeed been some improvements. Ingredient lists are now a legal necessity, and contemporary wearers tend to approach makeup as a conscious method of self expression and creativity rather than as a duty.

In some senses, though, it’s hard to miss the parallels to contemporary beauty tips dispensed by blogs and vlogs, and the potentially risky treatments that wax and wane in popularity and endorsements. “It’s kind of like how people say ‘Oh, Botox for your eye is probably not good’ while others say ‘but she looks so good now!’” says Karl. “So how far have we really come?”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook