The Rise and Suspiciously Rapid Fall of Freedomland U.S.A.

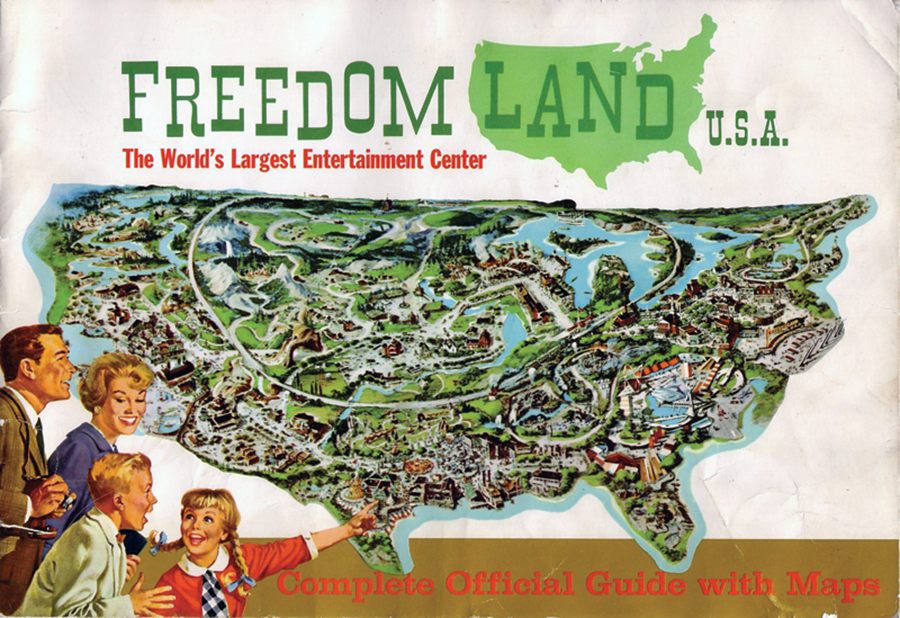

Freedomland brochure cover. (Photo: Mike Virgintino collection)

Freedomland U.S.A., an American history-themed amusement park in the East Bronx, was demolished 50 years ago this summer. But fond memories live on among Bronxites of a certain age, as do conspiracy theories about why the hugely popular pleasure garden lasted just five seasons, a suspiciously rapid demise.

History is the future at today’s theme parks. Whether it’s an immersive experience inside a World War I field hospital, a roller coaster whizzing through a 19th century mineshaft, or an entire park about Russian history, contemporary rides and attractions are designed to give visitors the feeling that they are part of a story from another time and place. Freedomland U.S.A. helped to inspire this trend more than five decades ago.

Billed as the world’s largest amusement park when it opened on June 19, 1960, Freedomland was quickly nicknamed the “Disneyland of the East.” Spread across 205 acres, the park dwarfed the actual Disneyland. For weeks prior to its debut, newspapers ran fervent articles hyping Freedomland’s ability to serve 50,000 hamburgers and hot dogs per hour, its eight miles of navigable waterways for river rides, its 8,500-car parking lot, and the 5,000 original costumes worn by its historical re-enactors.

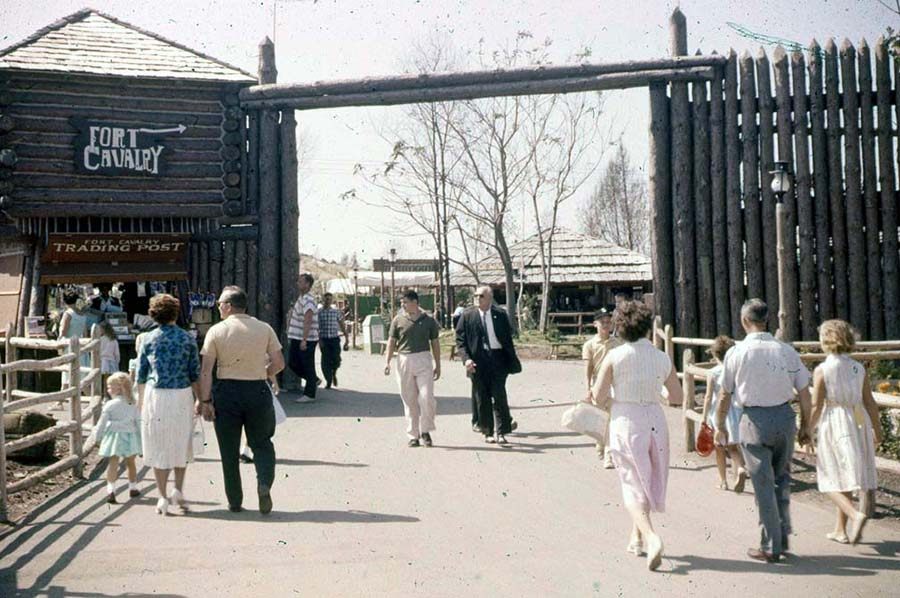

The Northwest Fur Trapper at Freedomland. (Photo: David Eppen)

The cost was just as newsworthy. “Twenty-two movie spectaculars could be produced for the investment in Freedomland,” The New York Times marveled. The $65 million price tag “is also equivalent to 195 top-budget Broadway musicals or 130 hour-long TV spectaculars.”

Twenty-five thousand people, breathless with anticipation, jammed the opening-day celebration.

They frolicked in a park layout that roughly mirrored the outline of the continental U.S., designed by Cornelius Vanderbilt Wood, an architect who led the planning team for Disneyland in the mid-1950s. Like its Californian predecessor, Freedomland was divided into seven regions: Little Ole New York, Old Chicago, the Great Plains, the Old Southwest, San Francisco, New Orleans—each with anachronistic shops on lively fake streets– and Satellite City, a town of the future modeled on Disney’s Tomorrowland.

Among the 37 attractions were the San Francisco Earthquake, a ride that tossed and jerked riders mercilessly; full-size paddleboats on the recreated Great Lakes, a western fort with daily shootouts, canoe cruises with Oregon fur trappers, and an amphitheater for live concerts called the Moon Bowl.

The star attraction was The Great Chicago Fire, where individual gas jets ignited buildings every 15 minutes and children ran to pump the fire hoses and douse the flames with a bucket brigade. Naturally, this was before the obsession with safety took hold.

“There was a couple fires before Freedomland even opened, and they took up some of the debris and put it in Old Chicago for the Chicago Fire exhibit. They didn’t waste too much money there,” laughed Tom Casey, secretary of the East Bronx History Forum.

The Great Chicago Fire, the star attraction at Freedomland. (Photo: David Eppen)

When the park opened, all-day admission was $1 for adults, 75 cents for teenagers, and 50 cents for children. Special ticket books that included admission and access to nine attractions cost $3.50 for adults, $3.20 for juniors, and $2.50 for children. Freedomland’s first season, from June through September 1960, counted 1.5 million visitors—an impressive number, but less than the five million that owners expected.

Soon, Freedomland ran into financial and cultural obstacles. Managers hoped customer turnover throughout the day would guarantee a profit, even with the cheap ticket prices. Customers, though, knew a good deal when they saw one. “They got there at 10 o’clock and didn’t go home ‘til after the fireworks,” Casey said.

For its second season, Freedomland introduced a variety of discounts and coupons to attract more visitors, even as the base price of admission went up to $2.50 for an economy ride ticket (though the concerts in the Moon Bowl were included).

“You know the jingle, ‘Mommy, Daddy, take my hand, take me out to Freedomland.’ The second part is, ‘50 cents is all you pay, at Freedomland today,’” said Casey. “I’ve heard a lot of people remember ‘75 cents is all you pay’ or ‘2.95 is all you pay,’ because the prices kept on going up, up, up.”

But attendance continued to dwindle over the next four seasons. Lingering debt from the park’s construction and its off-season closure between October and May each year mired Freedomland in the red.

Fort Cavalry, Freedomland. (Photo: Collection of Patrick Jenkins)

The park’s squeaky-clean image didn’t help matters. Freedomland struggled to survive after President Kennedy was assassinated in 1963. The event, often described as “the day the nation lost its innocence,” brought on a cultural shift that saw lighter diversions like amusement parks becoming less popular. At the same time, theme park design changed from nostalgic pleasures to thrills and chills.

“Freedomland should have opened in 1950, not 1960,” said Gregory Young, co-creator of the New York history podcast The Bowery Boys. “You’d never be able to get away with a whole section called ‘Old Chicago’ just ten years later.”

And when the park added late-night movies, more rides, and concerts by A-listers like Lesley Gore and Paul Anka to attract patrons, some of the sponsors revolted. The Benjamin Moore paint company even sued the park for $150,000 for “changing character” and becoming a hub for ”commonplace and vulgar mass unrestrained teen-age entertainment,” according to a 1962 article in the New York Times. The suit was dismissed as “groundless.”

“Scripto Pen, insurance companies, the banks, Kodak—they wanted to make sure that it maintained this historical significance, not just pure entertainment,” Casey said. “Over the years, some vendors did decide to leave because it really didn’t live up to that original idea.”

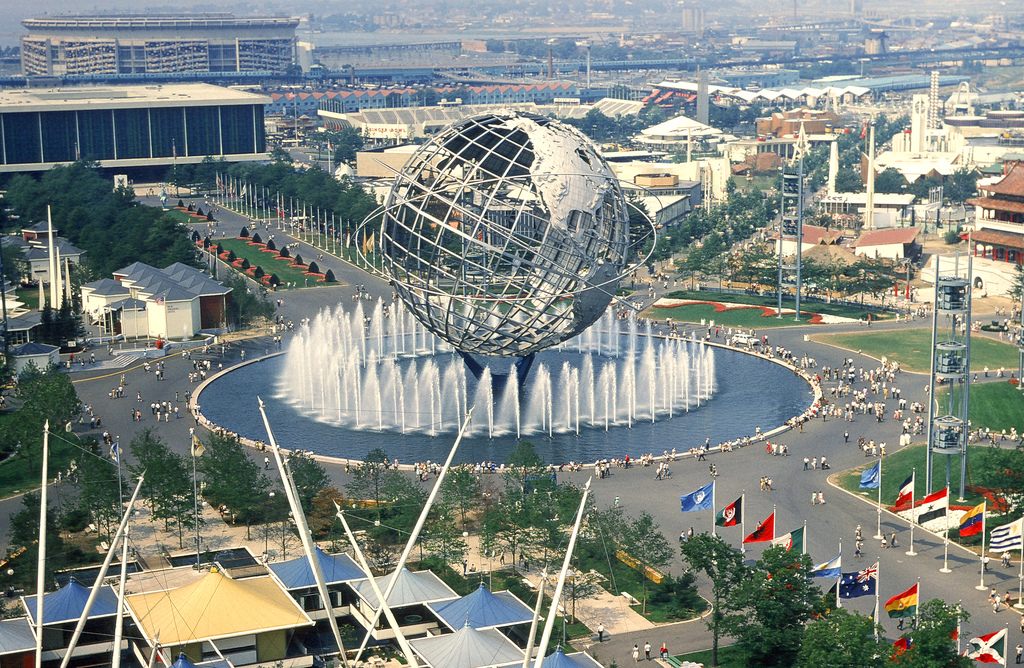

The last straw for Freedomland was tough competition from the glitzier, Robert Moses-backed 1964-1965 World’s Fair in Queens. Freedomland declared bankruptcy on September 15, 1964, and was demolished a year later.

The Unisphere in the center of the World’s Fair in Queens, which hastened the fall of Freedomland. (Photo: PLCjr/flickr)

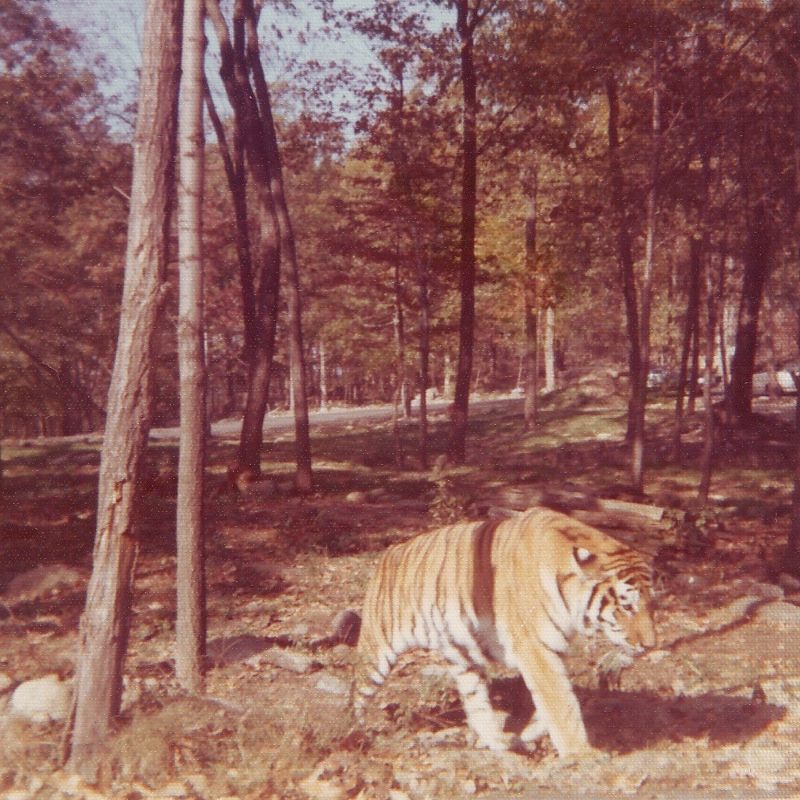

Sadly, Freedomland was not alone: failed amusements parks were endemic in the 1960s and 1970s. Jungle Habitat, which hung on for four years, closed in 1976 after its lions and elephants attacked visitors and rampaged through the New Jersey suburbs. The owners of the Pixie Kitchen restaurant in Lincoln City, Oregon, opened Pixieland—a theme park based on the state’s pioneer history—in 1969 and shut it down in 1973. The Land of Oz in North Carolina closed in 1980 after a decade of mediocre attendance (though it re-opens once a year for a Wizard of Oz fan day). Dogpatch USA, debuting in 1968 and starring the characters of Al Capp’s comic strip Li’l Abner, failed to find an audience around its Arkansas locale and petered out in 1993.

Briefest of all, The World of Sid and Marty Krofft, an Atlanta park featuring the Krofft’s cartoon characters, lasted six months in the summer of 1976.

New Jersey safari park Jungle Habitat, which closed in 1976 after the animals went bonkers. (Photo: David Powell/Flickr)

New Jersey safari park Jungle Habitat, which closed in 1976 after the animals went bonkers. (Photo: David Powell/Flickr)

But the speed of Freedomland’s destruction, and the immediate creation of the gigantic Co-Op City housing development on the site, fuels conspiracy theories today. Some fans are convinced that William Zeckendorf, a real estate mogul who owned Freedomland’s property, conspired with Cornelius Vanderbilt Wood to build federally subsidized housing on the site all along.

A news story at the park’s opening claimed its buildings “were built to last 50 years,” but historian Michael Virgintino believes that the structures were built just to prove the marshy Bronx shoreline could support multi-story apartment buildings.

“Their goal was always, ‘let’s use the land as we can now, until a better opportunity comes along,’” said Virgintino, who maintains the Freedomland U.S.A. Facebook page. “Freedomland was doomed from the start.”

All that remains of the park is a commemorative plaque marking the where the entrance gate once stood, placed there by Virgintino and other fans in 2013. Yet its legacy lives on in the fad for history-based attractions that fail to reach their potential.

Owners had high hopes for Hard Rock Park in South Carolina, a state-of-the-art theme park based on the birth of rock n’ roll, but it closed after a single season in 2008—only to be rebranded as Freestyle Music Park, which survived just as long. “Some said it just didn’t connect with guests,” says Scott Lukas, an anthropologist who studies theme parks. “This is too bad, since it had some very innovative rides, attractions and themes.”

A view of the abandoned Wonderland park in China. (Photo: JoeInSouthernCA/flickr)

Half-built a decade ago and demolished in 2013, Beijing’s Wonderland took its historical cues from the original Disneyland. Now Beijing Shijingshan Amusement Park wears China’s imitation-Disneyland crown. And the miniature historical landmarks of Splendid China, a theme park near Orlando that opened in 1993, shut down after a lackluster decade (its twin in Shenzen remains open for business).

None of these similarly short-lived parks have garnered the level of obsessive nostalgia that Freedomland has. Judging from the hundreds of personal memories posted to the Freedomland U.S.A. and East Bronx History Forum Facebook pages, the Bronx lost a valued piece of its identity 50 years ago.

One fan, Christopher Arena, wrote, “I was only there once, as a little boy, but I never forgot it.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook