Marie Curie Got Her Start At a Secret University For Women

The controversial Flying University.

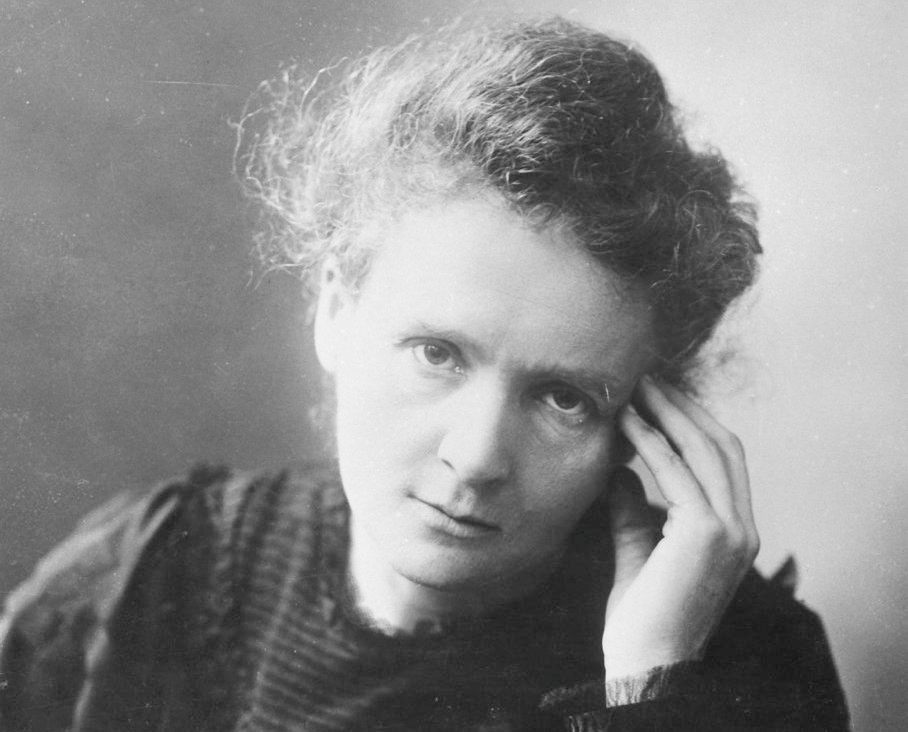

Before she won two Nobel Prizes, Marie Curie attended the Flying University. (Photo: Tekniska museet/CC BY 2.0)

If you think getting a college education is tough today, try earning a degree in Russian-controlled Poland in the late 19th century. If you were a man, you couldn’t be taught anything at university outside of the state-sanctioned curriculum, which was bad enough, but if you were a woman, you weren’t allowed to attend at all.

That’s where the Flying University, which produced Marie Curie and thousands of other students, came in.

By the middle of the 1860s, Poland had been parceled up between Russian, Prussian, and Austrian powers. One of the first things the country’s new rulers did was set out to limit and control Polish education. Like so many colonizing powers before and since, they knew that the first step in stamping out that pesky nationalism was to take it out of the history books. The Germanization and Russification efforts (depending on what political power controlled the part of Poland where you lived) aimed at higher education made it nearly impossible for the citizenry to take part in a curriculum that wasn’t in some way working to erase Polish culture. Even the teaching of Catholicism among a largely-Catholic population was taboo.

In the 1860s and 1870s, more educational opportunities were being made available to women in Poland, but universities still staunchly refused to admit them. In 1863, the Ministry of Education had actually sent out a decree to every university council in the country explicitly banning women from enrolling (to be fair, most all universities across Europe had policies forbidding women at the time). Any effort to give a complete education to the complete population would have to happen in violation of the new laws.

In the 1800s, the gates of Warsaw University were closed to women. (Photo: Witia/CC BY-SA 3.0 PL)

The Flying University began in the Polish capital of Warsaw in 1882, when secret classes for women began taking place in private homes. The lectures and seminars were taught by Polish philosophers, professors, and historians. Here they could not only receive a proper higher education, but also one that celebrated Polish heritage, free from the influence of outside powers. Hosting and organizing the classes was illegal under government statute, so to avoid detection they often changed location, moving from private home to private home. The classes came to be known as the Uniwersytet Latający, the Flying (or Floating) University.

These unincorporated classes, organized by various pockets of pro-education rebels, went on in and around Warsaw for years, but they were not formally brought together under one umbrella until around 1885. One of the students of the clandestine courses, Jadwiga Szczawińska, who has been described as possessing “formidable organizational ability,” got the idea to join the disparate classes together as a single covert operation. As the organization came together, even began creating a secret library that was funded by the small tuitions, which were also used to compensate the teachers. As the university formed, the coursework became more formalized as well, establishing a curriculum that covered sciences, history, math, theory, and more. What had begun as an informal rebellion evolved into an actual secret school.

With the freedom to provide a more complete, and patriotic, education, the Flying University was able to employ some of the country’s finest academic minds, giving the school a reputation for providing a higher standard of education than any of the formal universities. As more male students heard of the university’s success, they also wanted to take part, and by the 1890s, the Flying University had near a thousand students from both sexes.

While the university couldn’t grant its students any sort of official degree, it did have graduates. As noted in a piece over on Open Culture, easily the most famous of the students who took part in the Flying University was Curie, the mother of radioactivity who would go on to win multiple Nobel Prizes for her work. Curie, a Warsaw native, joined the university with her sister, prior to earning her first official degrees in France.

Marie Curie and her husband at work. (Photo: Wikipedia/Public Domain)

The Flying University remained in operation until 1905 when changing attitudes in government allowed it to come out of hiding. Sensing the coming of World War I, the Russian and Germanic powers made moves that they hoped would make the Polish people warm to them, including loosening the restrictions on education. Once the university could operate legally, it established itself as the Society of Science Courses, and later as the Free Polish University.

A second incarnation of the Flying University appeared again in the mid-20th century in response to a post World War II effort by Communist Russia, who once again took control of Poland, to send the memory of previous Polish-Russian conflicts down a memory hole. Where the first Flying University seemed to have operated relatively without conflict with the government, the second incarnation was a more contentious, and outwardly political affair, with supporters of the institution often getting brutalized by Soviet thugs. The second university eventually disbanded at the end of the 1980s as Poland moved towards democracy.

Today there are over 500 colleges and universities across Poland, offering both women and men the opportunity for a balanced and comprehensive education. No flying needed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook