The Self-Made Castaway Who Spent 16 Years on an Atoll With His Cats

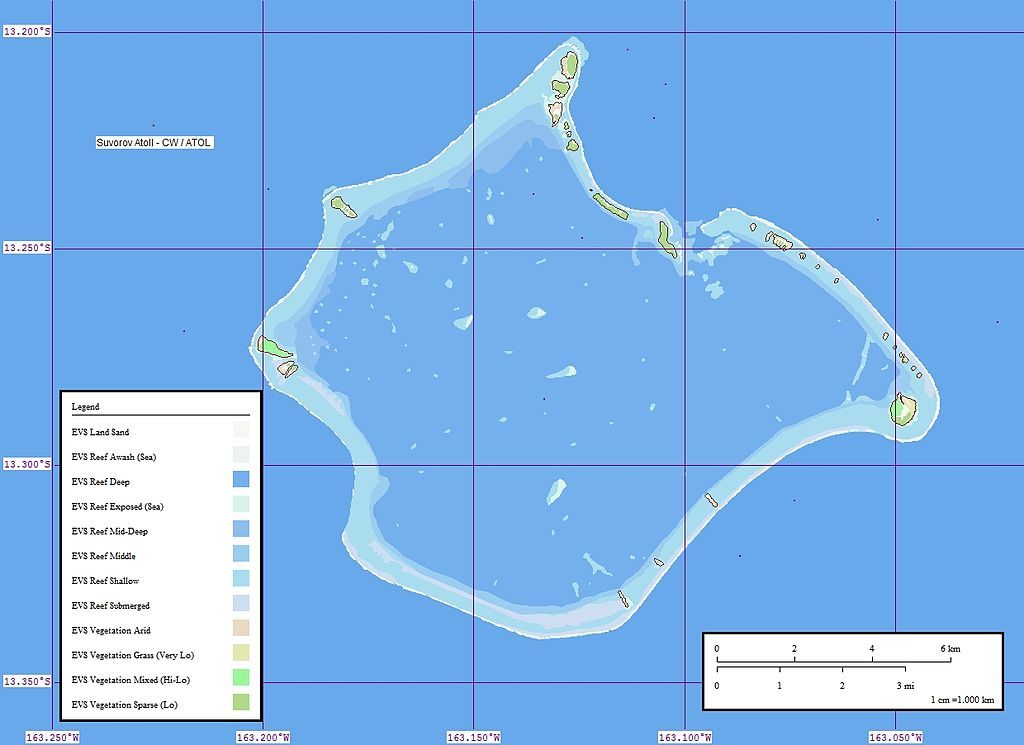

Anchorage Island on Suwarrow Atoll. (Photo: Suwarrow/Creative Commons)

The phrase “sole survivor” evokes scenes of violent disaster—a plane crash; an explosion in a mine; the eruption of a volcano whose lava destroys a city and all its inhabitants but one. The horrific details make an indelible impression on the survivors and those who hear their stories. One woman survived a Peruvian plane crash that killed 91 and stumbled injured through the jungle for days, during which she had to dig out 30 maggots that had burrowed into a gaping wound on her arm. In 2005, a man survived the Sago mine explosion that released toxic methane and carbon monoxide, slowly killing his 11 co-workers as they wrote final letters to their loved ones.

These are traumatic tales. But not all sole survivors have been through a hell unleashed on them by fates beyond their control. Another kind of “sole survivor” is one who survives solo. Take the story of Tom Neale, dumped by boat on a tiny atoll in the Pacific, where he lived alone for 16 years. Neale, a New Zealander, rode out violent storms in a rickety shack, ate a diet heavy on fish and coconuts, and wore nothing but a loincloth. It is the remarkable tale of a shipwrecked survivor, but for one detail: Neale did not land on the atoll by accident or during a terrible storm. He traveled there willingly and enthusiastically, determined to live a simple, solitary existence on an island he could call his own.

Formerly a shopkeeper, Neale became fixated on the tiny Cook Island atoll of Suwarrow (also known as Suvorov) in 1943, when author and traveler Robert Frisbie spoke of it to him after visiting. In his memoir, An Island to Oneself, Neale wrote of their conversation:

That afternoon Frisbee entranced me, and I can see him now on the veranda, the rum bottle on the big table between us, leaning forward with that blazing characteristic earnestness, saying to me, “Tom Neale, Suvorov is the most beautiful place on earth, and no man has really lived until he has lived there.”

In 1945, a ship passed by Suwarrow—which is 200 miles from the nearest populated land—to drop off supplies for the coastwatchers New Zealand had stationed there during World War II. Neale hitched a ride and saw Suwarrow’s gently swaying palm trees, pristine sands, and soothing turquoise waters firsthand. Enchanted, he decided he simply must live there.

Suwarrow Atoll. (Photo: NASA World Wind/Public domain)

To prepare for his stay, which he envisioned would last for years, Neale stockpiled supplies. On the island of Rarotonga in the Cook Islands, he perplexed store owners by buying their entire inventories of flour, sugar, kerosene, and coffee beans. As word spread about his grand plans, villagers offered gifts and even companionship. Neale politely refused the advances of several women who asked to accompany him, suspecting it would not be long before he came to resent their company. He did, however, choose two non-human companions: a cat named Mrs. Thievery (named for her favorite hobby), and her kitten, Mr. Tom-Tom.

Armed with tins of food, tools, seeds, and a motley collection of paperbacks, Neale arrived on Suwarrow following six days at sea. The island was bereft of any human presence, but World War II coast watchers had left behind a hut with water tanks, which would become his home.

Neale’s life on the atoll is described in fascinating detail in An Island to Oneself. As he wrote, he soon fell into a routine, spending the daylight hours building, cleaning, and tending to the garden he had made. As day turned to evening he would sit on a wooden box at the beach, watching the sun set while drinking a bowl of tea. But there were less comforting chores, too. The task of killing six pigs who threatened to destroy the garden brought Neale much anguish—after spearing the first one and hearing its screams, he wrote in his journal of feeling “melancholy,” and decided to bury the animal rather than eat it.

Ten months after his arrival on Suwarrow, Neale received his first visitors: two couples on a yacht, who were astonished by the orderliness of his abode. Not one to lower his living standards just because he lived in a shack, Neale boiled his sheets weekly, kept a tidy room, and ate his meals on a tablecloth. When the visitors departed a few days later, leaving well wishes and a half-drunk bottle of rum, Neale took up a new project: reconstructing a destroyed pier that had embarrassed him with its unsightliness.

For the next six months, he spent up to five hours every day dragging, rolling, and carrying coral stones to the water’s edge, setting them on the pier’s fragmentary foundations. When the interminable task was finally complete, Neale had single-handedly built a neat, structurally sound jetty using just rocks, patience, and hard work. The next day, a violent storm attacked the island, completely destroying the newly finished pier.

(Image: Mr Minton/Creative Commons)

Thus began a run of bad luck. Having exhausted his tobacco supply, Neale experienced torturous cravings. He dreamed nightly of soothing cigarettes, chocolate, beef, and fat, juicy ducks. But the mental torture would soon pale in comparison to physical pain. Casting an anchor on the beach one day, Neale felt a searing stab along his spine and suddenly every movement was agony. In his memoir he wrote:

When I stood still I felt no pain, but the instant I tried to move, the smallest action sent spasms galloping through every muscle. … I was certain I had dislocated my back, and remember telling myself, “Neale, if you give in, this is the end.”

Taking four hours to make the short journey back to his shack, Neale laid down in his bed and, between bouts of unconsciousness, hoped for a miracle. Incredibly, one arrived—in the form of Peb and Bob, two American yachtsmen who stopped in at the atoll while en route to Samoa. (Peb, as it turned out, was more formally known as James Rockefeller Jr., a member of one of the United States’ wealthiest dynasties.) The duo, astonished to find Neale on the “uninhabited” island, fed him, massaged his back, and, having returned him to good health, departed with a pledge that they would send a ship to fetch him. Two weeks later, the promised ship arrived, plucking Neale from his two-year life of island solitude and ferrying him back to Rarotonga.

The comparatively bustling island of Rarotonga. (Photo: mercyrains/Creative Commons)

Neale did not take kindly to being back among the comforts of civilization. Clocks were an intrusive nuisance, cars moved noisily and too fast, and trousers compared unfavorably with the comfort of a cotton loincloth. All Neale wanted was to return to Suwarrow, but the government forbade it. Disconsolate, he took a job in a warehouse. Six years passed before a friend with a 30-foot boat offered to take Neale back to his beloved atoll. Honor-bound, Neale visited Rarotonga’s Resident Commissioner to inform him of his plans and received off-the-record approval.

Neale’s second stay on Suwarrow lasted two-and-a-half years, only ending when the increasing presence of pearl divers at the atoll began to wear on his patience. A three-year break in Rarotonga allowed him to pen An Island to Oneself before returning for his final, decade-long stay on Suwarrow. In 1977, stricken with stomach cancer, he was transported back to Rarotonga, where he died at the age of 75.

Despite his long stretches of solitary living, Neale claimed he never felt lonely. The few times he wished someone were with him, he wrote in his memoir, were “not because I wanted company but just because all this beauty seemed too perfect to keep to myself.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook