The Sexual Intimidation Tactics of the Male Water Strider

Their mating rituals are pretty disturbing.

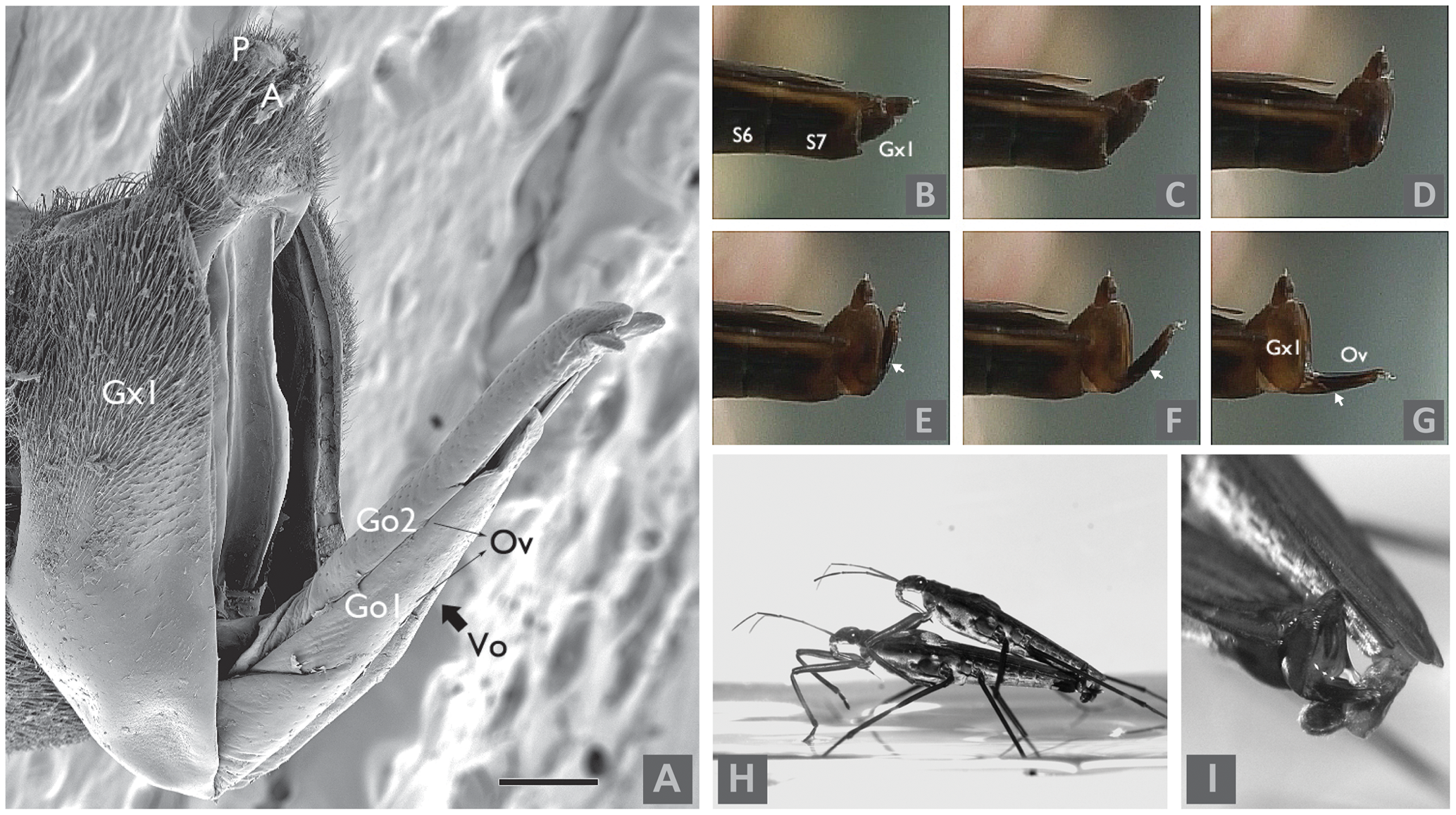

Water striders mating, probably after coercion. (Photo: Markus Gayda/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Water striders mating, probably after coercion. (Photo: Markus Gayda/CC BY-SA 3.0)

When a male water strider wants to mate, he skips the small talk and goes straight for the death threats.

That was the finding of a 2010 study, which found that male water striders of the genus Gerris want sex so badly that they coerce a female into it by strumming the water to alert and attract predators—predators that might approach and swallow her up.

Water striders, also known as “Jesus bugs,” have garnered fame for their ability to “walk” on water. Tiny hairs on their legs capture air and repel water, allowing them to stay afloat by taking advantage of water’s surface tension. But now their messianic walking method is not the only reason they’re notorious in the insect world.

Two water striders lock eyes before the romance turns to aggression. (Photo: Alexander/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Two water striders lock eyes before the romance turns to aggression. (Photo: Alexander/CC BY-SA 2.0)Jen Perry, a postdoctoral fellow at Oxford University who’s researched sexual behavior in water striders, says female striders, who can store the sperm from a single mating for a weeks, are biologically inclined not to prefer reproduction. This is because she literally has to carry to male around—post-copulation, the male water strider passively rides on the back of the female for anywhere from a few minutes to two days, causing her to forfeit her foraging efficiency.

Because the males want to maximize their offspring, there’s an evolutionary conflict. Gerris gracilicornis females have a hard genital shield that only allows them to mate when they open it. That’s where the males react with their own behavioral adaptation—strumming the water. As a male is precariously perched on the female’s back, he’s free to “skate away,” Perry says. Meanwhile, the female must bear the risk—or actual brunt—of an attack by an aquatic predator.

A typical predator? A backswimmer—an upside-down-swimming aquatic insect of the Notonectidae family—a duck, or a bird, truly formidable foes. When these predators approach the female, she can either continue to resist the male and risk becoming lunch or give in to his sexual aggression.

A backswimmer looking for some delicious water strider. (Photo: JRxpo/CC BY-SA 2.0)

A backswimmer looking for some delicious water strider. (Photo: JRxpo/CC BY-SA 2.0)Perry studies sexually antagonistic coevolution—what she calls “an endless tug of war” between the sexes of the same species—in ladybird beetles, fruit flies, and water striders.

She says males of the Gerris genus come stocked with a whole lot of evolutionary adaptations that help them ward off females’ attempts to, well, ward them off. For one, their enlarged forelegs and elongated spines allow easy gripping access, making mounting a female and grabbing on that much easier.

Though males’ aggressive tactics and appendages present a challenge, females aren’t left without a way to fight back. Those of the Gerris genus have enlarged spines above their genital openings—the same spines that males use to wrap around the females to keep them still for copulation, Perry says. The females’ spines make mating more difficult, as the males can’t access the genital opening, which can also be blocked by the genital shield.

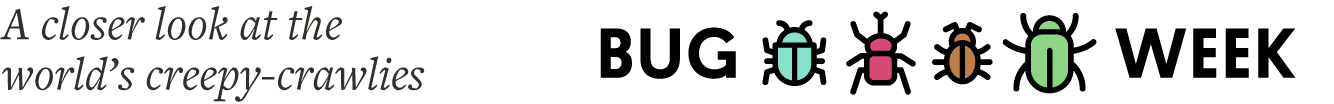

The image on the left shows a close-up view of a female water strider’s genital shield, with its inflation illustrated in pictures B through G. (Photo: Han CS, Jablonski PG (2009) Female Genitalia Concealment Promotes Intimate Male Courtship in a Water Strider/PLOS)

The image on the left shows a close-up view of a female water strider’s genital shield, with its inflation illustrated in pictures B through G. (Photo: Han CS, Jablonski PG (2009) Female Genitalia Concealment Promotes Intimate Male Courtship in a Water Strider/PLOS)They also adopt defensive behavioral strategies, such as tossing the male around until he can’t hold on, or leaving the area to go find solitude elsewhere.

Researchers at one point considered that the tapping could be a mating song—a romantic ballad, an alluring enchantment. But evidence now points to less of a seduction on the male’s part and more of a surrender on the female’s part. It’s clear the world of semiaquatic sex is one of battles and brutality.

Piotr Jabłoński, a professor in the School of Biological Sciences at Seoul National University in South Korea, studies sexual selection in birds and water striders. He says evolutionary mechanisms often pit the two sexes of a species against one another.

“Natural selection does not produce what is best for the species,” he says. “It produces what is best to increase offspring number in a lifetime of an individual, and if this leads to behaviors that are not so ‘good’ for a smooth and nice life—it does not matter as long as long as the number of offspring in the lifetime of an individual is maximized.”

In many cases, females are simply choosing the lesser of two evils—as Jabłoński puts it, a predator attack is “more fatal” to the females than simply allowing the males to fornicate forcibly with them.

This video posted by the account Wandering Sole Images illustrates the ferocity behind these predatory vibrations. Around 0:36 the mounted male’s legs make ripples so intense they’re like a strider-sized tsunami. Skip to 1:16, and the thrashing becomes so violent that the couple of copulators actually somersaults in the water as the female seeks to defend herself. The bug world is a scary place.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook