The Truth and Myth Behind Animal Trials in the Middle Ages

(Image: Wikipedia)

(Image: Wikipedia)

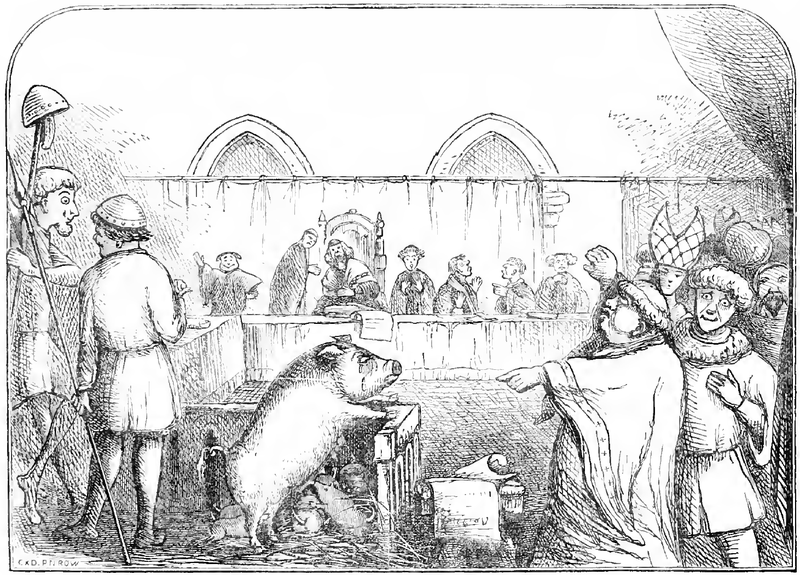

Weevils destroy your crops? Pig maim your children? Dying to get back at these creatures? In Europe during the Middle Ages, you could bring them to court, where they could face sentences ranging from gruesome mutilation to excommunication. Or at least that is what many reports say, although the hard evidence of such legal actions is scant.

And somehow, the surreal practice of trying beasts as though they are people continues to this day.

The main issue with our understanding of the strange practice, according to Sara McDougall, associate professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, is the sourcing. “The sources are 19th century scholars who didn’t bother to give a whole lot of explicit information on where they found the stuff,” she says, “With a lot of the medieval ones we know that some of them were either made up or they were textbook cases that were kind of a way to keep students from falling asleep.” In an even stranger reasoning for an fake animal court story, McDougall says that one of the most famous cases of beasts on trial, involving a bunch of rats, was “completely made up just to defame the lawyer who supposedly defended the rats.”

Even with so much uncertainty about which animal trials were real, McDougall stresses that some did still take place.

The most detailed source of case studies (whether real or imagined) we have for the medieval (roughly between the 13th and 16th century) practice of putting animals on trial is E.P. Evans’ treatise on the subject, The Criminal Prosecution and Capitol Punishment of Animals, published in 1906. Evans points out two distinct types of animal trials that would occur:

[There is] a sharp line of technical distinction between Thierstrafen and Thierprocesse; the former were capital punishments inflicted by secular tribunals upon pigs, cows, horses, and other domestic animals as a penalty for homicide; the latter were judicial proceedings instituted by ecclesiastical courts against rats, mice, locusts, weevils, and other vermin in order to prevent them from devouring the crops, and to expel them from orchards, vineyards, and cultivated fields by means of exorcism and excommunication.

In other words, most large animals were tried for offenses such as murder, and generally executed or exiled, while smaller, more diffuse pests and offenders were more often excommunicated or denounced by a church tribunal. But all were thought to have been given their day in court.

Evans’ book lists around 200 cases where all creatures large and small were brought to trial for a plethora of reasons.

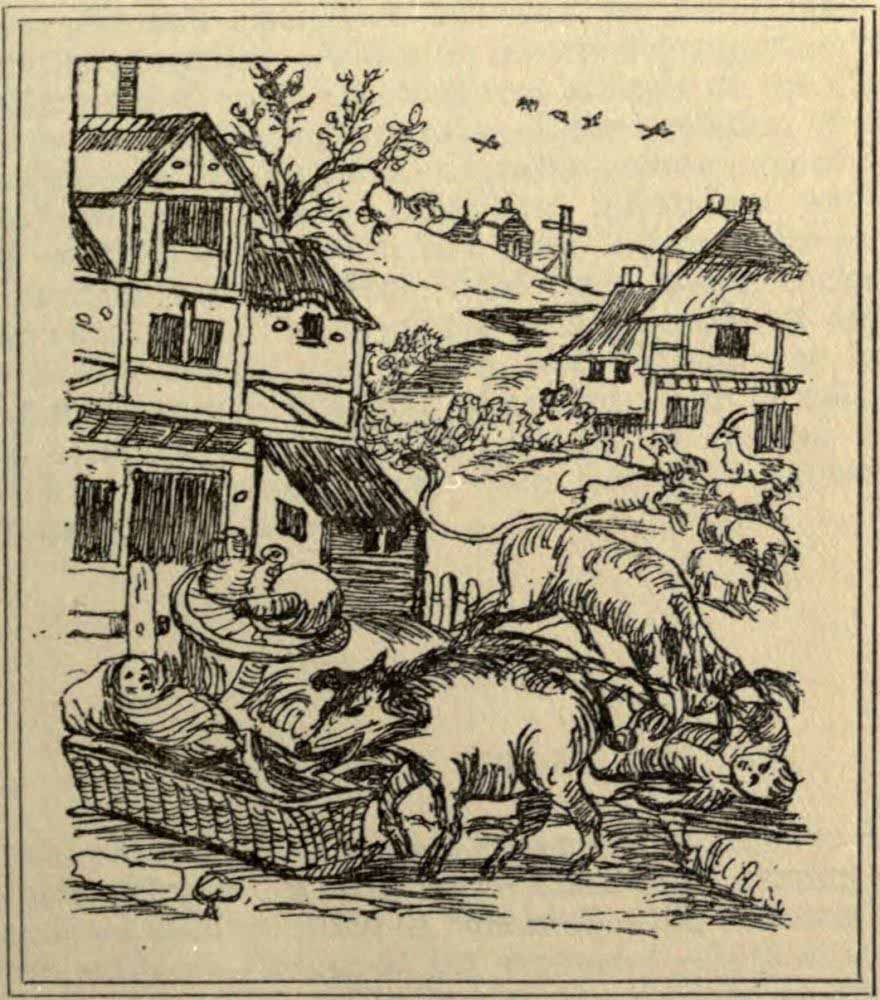

Most complaints against smaller animals leveled for infestation or destruction of crops ended up in some sort of excommunication from the church, or official ecclesiastical denouncement. Evans explains that this was largely done as an effort to make people feel better about exterminating them. Since even weevils, slugs, rats, and such were considered God’s creatures, the devastation they inflicted was likely part of his plan, so to just destroy them would be to act against God’s will and creatures. Of course if they were tried in a church court, and excommunicated (or condemned in the case of animals and insects), that could mitigate guilt.

One such case in the 1480s saw the Cardinal Bishop of Autun in France rule against some slugs which were ruining estate grounds under his purview. He ordered three days of daily processions where the slugs were told to leave the area or be cursed, thus making them free game for extermination. A similar case was said to have taken place just a year later.

(Image: Gutenberg.org)

(Image: Gutenberg.org)

In the case of larger animals such as bulls, pigs, dogs, cows, and goats, the offending beasts which could, in theory, actually be brought to court to stand trial. The sentences for these animals tended to be more severe.

Pigs often got the worst of the human legal system, for a simple reason. “They were killing people,” says McDougall.

In an age where animals were often roaming the streets and children were found in the fields, accidents were pretty common. Evans describes one, fairly typical case in 1379 in which two herds of swine were feeding together when a trio of pigs became agitated, and charged the swinemaster’s son, who died from his injuries. All of the pigs from both herds were tried, and “after due process of law, were condemned to death.” Somewhat luckily, all but the three instigating pigs were implicated as accomplices, and later pardoned.

In most cases, the court endeavored to try the animal as closely as it could to the same way humans were tried. This included how they were punished. Just like some murderers of the day, condemned animals (again, in most cases, pigs), were horribly executed for their crimes. Evans described a pig in 1266 who was publicly burnt for the crime of mutilating a child, and another in 1386 that was “to be mangled and maimed in the head and forelegs, and then to be hanged, for having torn the face and arms of a child.”

Beastiality was also an occasional accusation that led to the trial of an animal, although this charge was actually known to go in the animal’s favor. “Both the human and the animal might be put to death, but in some cases, they seem to have managed to say that it wasn’t the animal’s fault, that the animal didn’t consent,” she says, “So the animal wasn’t punished.”

Still other animals were imprisoned right along with human criminals. In this case, as no one honestly believed the animal was solemnly considering its actions, the owner was charged for the animal’s board as a form of second-hand punishment.

As barbaric, strange, or just silly as animal trials may seem, they continue well into the modern day. In 1916 an elephant named Mary murdered her trainer and was hanged in Tennessee using a crane. In 2008, in Macedonia, a bear was convicted of stealing honey from a beekeeper. The parks service was forced to pay $3,500 in damages. It seems like the human thirst for justice, no matter how irrational or silly, continues to know no bounds.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook