Think Kanye’s Bad With Money? This Family Literally Burned $1 Million

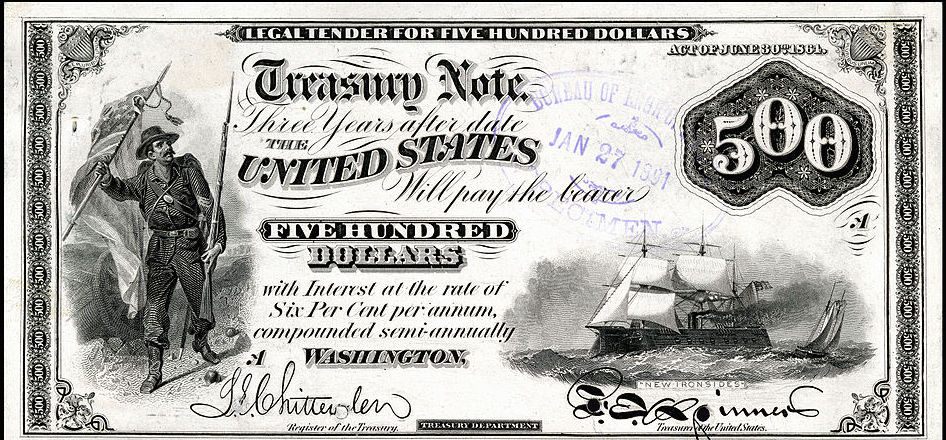

An 1864 series $500 bill (Photo: National Museum of American History/Wikimedia)

In 1937, one of the wealthiest families in America delivered a suitcase filled with cash to the Treasury Department of the United States, who paid $198,176 to one of the richest families in America, for a pile of money worth as much as $1 million. They didn’t go on a shopping spree, though.

In fact, after the Treasury took possession, the Associated Press reported, that cash was “hacked to pieces and burned.”

The Treasury did keep one bill—a $500 note that the Treasury had issued in the mid-19th century. It was in better condition than the one in the official Treasury collection.

Far from an example of government overreach, this strange incident of money-burning was a canny strategy to make the estate of one Colonel E.H.R. Green even more valuable. It was also a preamble to the demise of one of the greatest currency collections ever assembled.

This collection was begun by Hetty Green, the only female tycoon of the Gilded Age. Green was famously tight-fisted with her money—she lived in Brooklyn and Hoboken to avoid paying Manhattan taxes—but found physical bills fascinating (and valuable) enough that she started amassing rare currency, along with regular old money.

Although coin collecting had been in vogue for centuries, until the 1940s, collecting paper money was rare. Even then, coin collecting was more prestigious. “Until recently, the derisive term used by coin collectors to characterize those of paper money was ‘ragpickers,’” says Art Friedberg, co-author of Paper Money of the U.S.

Colonel Green, Hetty’s son, inherited half of her fortune and was himself a famous coin collector. After he died in 1936, though, neither his sister nor widow, fighting over his estate, seemed interested in the family hobby.

Col. Green’s mansion (Photo: Aaron Sherman/Wikimedia)

At the time, the Green currency collection contained two of almost every banknote ever issued by the U.S. government, the AP reported. This was one of the two “greatest collections of paper money ever formed,” Freidberg notes in his book. The other belonged to Albert A. Grinnell, and when it was broken up, beginning in 1944, it took seven auctions to sell it all off.

Before selling the Green collection, though, the estate’s advisor, James Wade of Chase National Bank, convinced the family to prune back the collection, so that it contained only one of every bill. Treasury policy was to destroy currency no longer in circulation, and by turning over those rare bills, the Green estate had a chance to increase the value of the remaining bills even further. (The Treasury still will destroy bills that are damaged or otherwise unusable.)

It was good advice, since the Green estate did have money to burn. According an appraisal, Friedberg says, the collection had 61,664 pieces of paper money at the time. “Whatever was ostensibly burned was a drop in the bucket and, indeed, would have made what was left more valuable,” he says.

A few years later, in 1942, the collection was sold privately. While auctions mean auction catalogues, private sales leave no public records, so it’s impossible to know what exactly what was in that collection—or what rare bills the Treasury burned. Since then, currency collecting has become popular (and competitive) enough that no new suitcase filled with money has ever rivaled the Greens’.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook