Today Me, Tomorrow You: Rome’s Sculptural Skeletons

Sant’Agostino, memorial to Cardinal Giuseppe Ranato Imperiali, by Paolo Posi (design) and Pietro Bracci (statuary), 1741 (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

Sant’Agostino, memorial to Cardinal Giuseppe Ranato Imperiali, by Paolo Posi (design) and Pietro Bracci (statuary), 1741 (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

The dead are everywhere in the churches of Rome. Their tombs line the walls and dominate whole side chapels. Visit enough of them and you’ll come to expect the loose wiggle and hollow thunk of the marble slabs shifting beneath your feet that signal you’ve walked over a grave. If you imagine what’s just beyond every surface, the churches become mega-necropoli, Tokyos made of tombs instead of hotel rooms.

Unlike the relics of the saints, the entombed bodies of clergy and parishioners are largely hidden from the public, but the Baroque skulls and life-sized marble skeletons won’t let you forget they’re there. They speak to you. But as David Sedaris noted in When You Are Engulfed in Flames, the skeleton has a “limited vocabulary, and says only one thing: ‘You are going to die.”

Rome’s skeletons prefer to deliver the bad news in Latin, an appropriately dead language, but even so you can’t mistake the message or the fact they’re addressing you directly. An engraved skeleton on the façade of Santa Maria dell’Orazione e Mort unfurls a banner that reads, “Hodie mihi. Cras tibi.” “Today me. Tomorrow you,” it shrugs.

Though their message is grim, the skeletons are surprisingly lively. At San Francesco d’Assisi a Ripa Grande, they climb out from behind the artwork. At Gesù e Maria, one appears frozen in the middle of a solo danse macabre, flailing so wildly it seems to be coming apart. Even in the more staid examples, it isn’t unusual for the skull’s empty sockets to convey more emotion than busts of the living. It’s this kinetic quality that’s so arresting; life seems to bursts supernaturally from these dark corners devoted to death.

The juxtaposition is intentional. Bernini popularized the use of these unusually active skeletons, and in doing so masterfully expressed a tenant of his Catholic faith. The feathered wings signal these aren’t your average corpses. They’re complex allegories for the inescapable passage of time, and the belief that death and decomposition of the body are the first stages in the transition to everlasting life (or damnation, as the case may be). Though the skeleton may only say, “You are going to die,” for some that implies, “You haven’t lived yet.”

Sant’Eustachio (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

Sant’Eustachio (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

San Lorenzo in Damaso, memorial to Allessandro Valtrini by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, 1639 (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

Gesù e Maria, memorial to Camillo del Corno by Domenico Guidi (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

Gesù e Maria, memorial to Camillo del Corno by Domenico Guidi (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

Façade of Santa Maria dell’Orazione e Morte, designed by Ferdinando Fuga, 1738 (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

Façade of Santa Maria dell’Orazione e Morte, designed by Ferdinando Fuga, 1738 (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

Santa Maria del Popolo, tomb of Giovanni Battista Gisleni, made for himself prior to his death in 1672 (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

Santa Maria del Popolo, tomb of Giovanni Battista Gisleni, made for himself prior to his death in 1672 (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

Santa Maria del Popolo, tomb of Princess Maria Eleonora Boncompagni Ludovisi, died 1745 (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

Santa Maria del Popolo, tomb of Princess Maria Eleonora Boncompagni Ludovisi, died 1745 (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

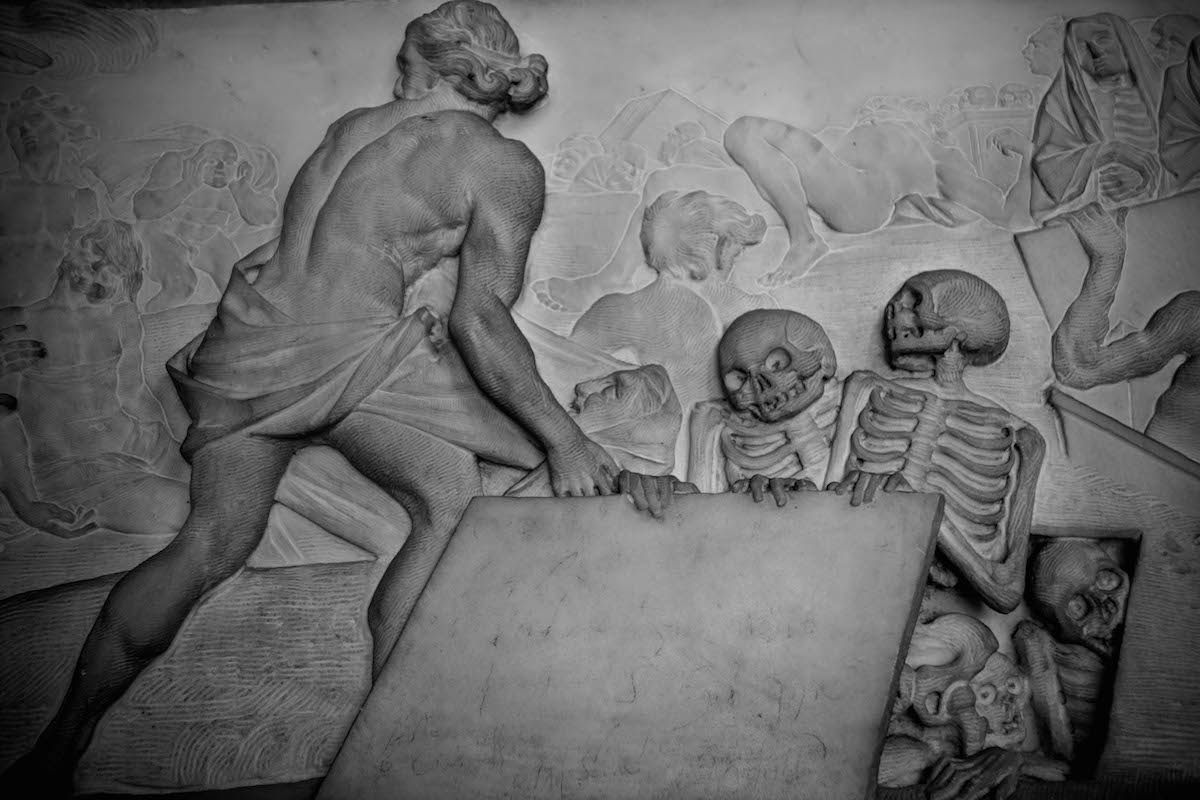

San Pietro in Montorio: Detail of the relief carved on the tomb of Girolamo Raimondi by Niccolo Sale, chapel designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

San Pietro in Montorio: Detail of the relief carved on the tomb of Girolamo Raimondi by Niccolo Sale, chapel designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

San Pietro in Vincoli, memorial to Cardinal Cinzio Aldobrandini by Carlo Bizzaccheri, died 1610 (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

San Pietro in Vincoli, memorial to Cardinal Cinzio Aldobrandini by Carlo Bizzaccheri, died 1610 (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

San Pietro in Vincoli, memorial to Cardinal Mariano Pietro Vecchiarelli, died 1639 (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

San Pietro in Vincoli, memorial to Cardinal Mariano Pietro Vecchiarelli, died 1639 (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

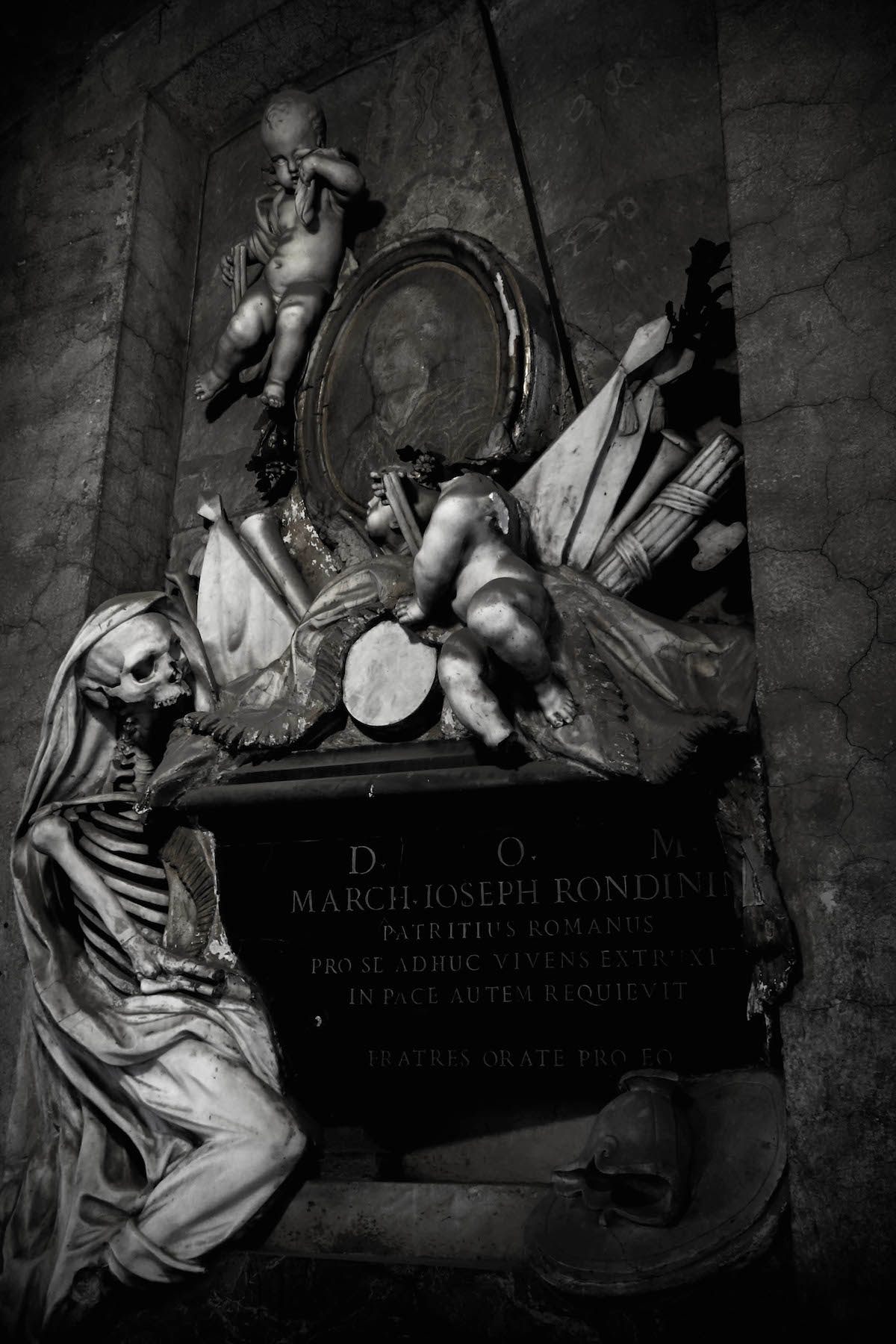

Sant’Onofrio, tomb of Marquis Joseph Rondinin (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

Sant’Onofrio, tomb of Marquis Joseph Rondinin (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

Santa Maria sopra Minerva, memorial to Carlo Emanuele Vizzani, by Domenico Guidi, 1661 (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

Santa Maria sopra Minerva, memorial to Carlo Emanuele Vizzani, by Domenico Guidi, 1661 (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

San Francesco d’Assisi a Ripa Grande, memorial to Maria Camilla and Giovanni Battista Rospigliosi, skeleton by Michele Garofolino, 1713 (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

San Francesco d’Assisi a Ripa Grande, memorial to Maria Camilla and Giovanni Battista Rospigliosi, skeleton by Michele Garofolino, 1713 (photograph by Elizabeth Harper)

Elizabeth Harper writes about saint relics and other morbid history at All the Saints You Should Know. You can also find more on the remains of the holy departed at the All the Saints You Should Know Facebook page.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook