96-Year-Old Barney Smith Is Giving Up His Toilet Seat Museum

Wanted: A worthy buyer to take care of over 1,300 hand-decorated seats.

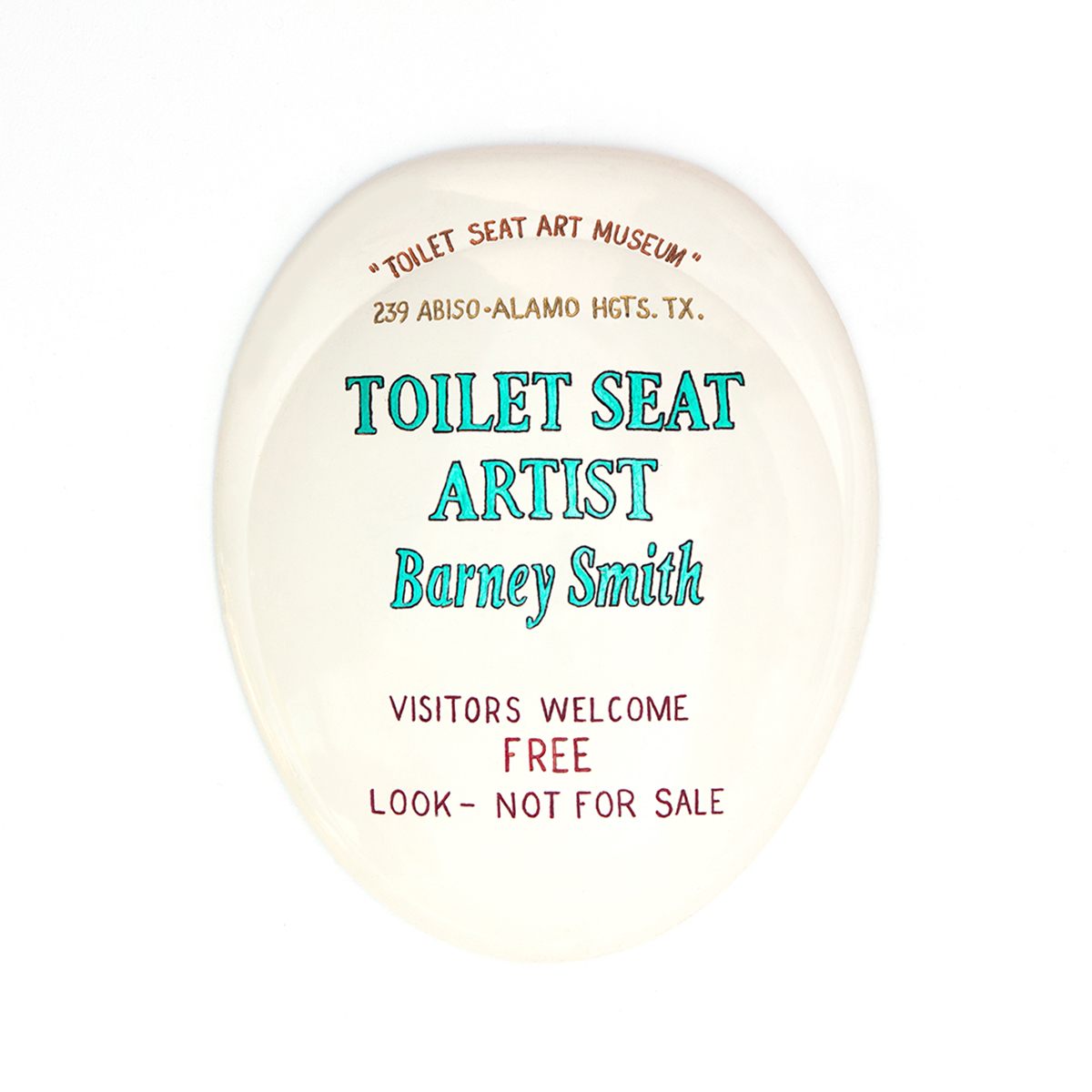

Most visitors to San Antonio know it for the Alamo, the Missions, or the Riverwalk. These well-known tourist centers draw millions to the city. But for the past 25 years, a steady stream of oddity seekers has used the road less traveled to see a local bastion of folk art. His work isn’t displayed in a trendy gallery or exhibition, but it is appointment only. Visitors drive into the heart of an upper-class neighborhood called Alamo Heights until they arrive at a garage. When the metal doors swing open, there stands Barney Smith and 1,300 toilet seats.

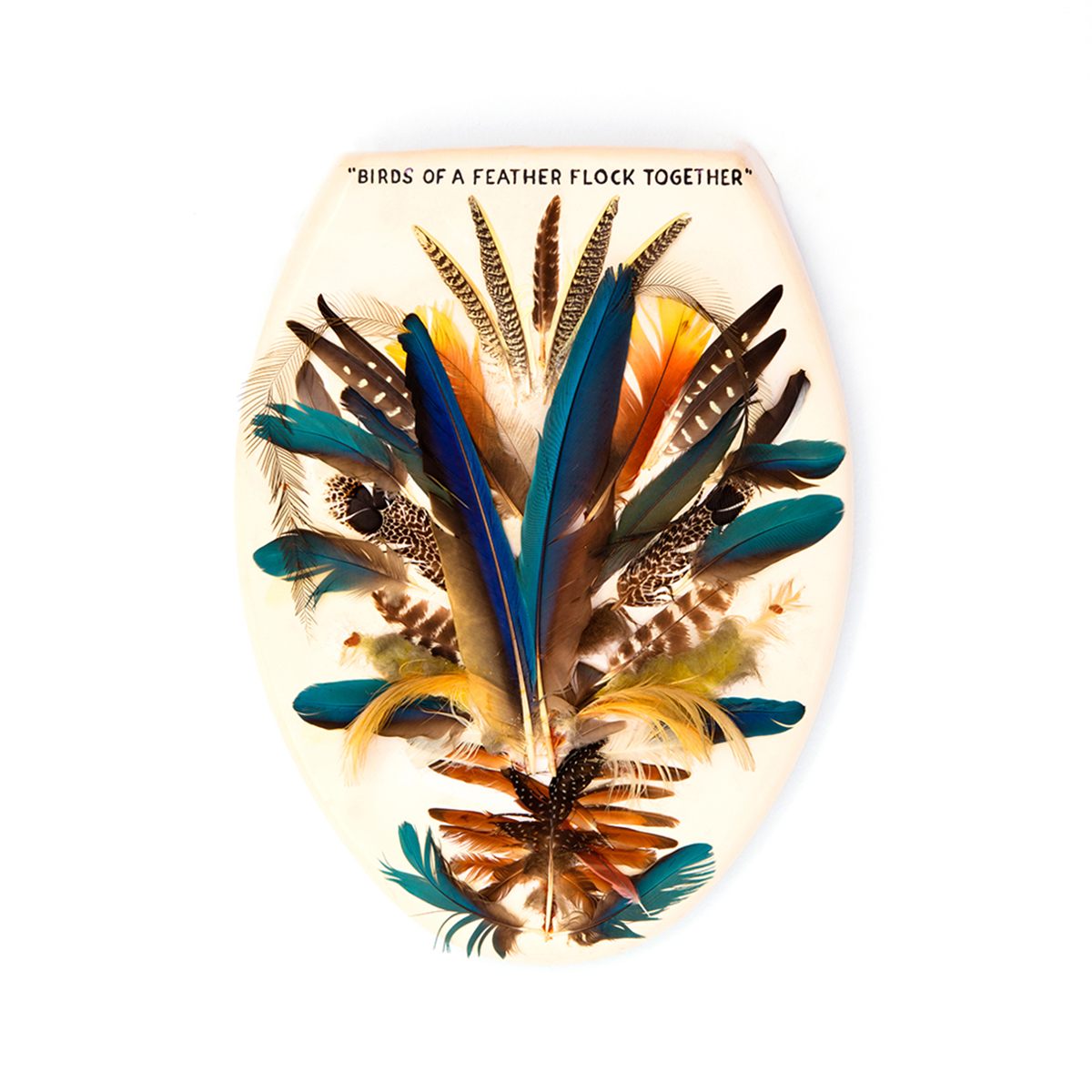

The 96-year-old Smith is a retired master plumber who was inspired to put artwork on toilet seats by the hunting mounts made by his father. His first seat is adorned with deer antlers, but he’s found inspiration in almost anything under the sun. For the past 50 years, he’s poured thousands of hours and nearly every thought into making toilet seat art. Why?

“Because I’m still alive,” he exclaims. “Is that a good enough reason?”

He didn’t make his collection viewable to the public until 1992, when another artist saw Smith’s seats during a garage sale. After Smith showed off the the full collection, word got around. His phone started ringing off the hook.

“People demanded to see it,” he says. “It’s the people’s museum.”

It’s also the only museum of its kind in the world. His visitors come from all over that world, usually leaving behind a memento for Smith to place on a toilet seat. He has commemorative toilet seats to mark guests from Israel, Brazil, Greece, Japan, and several others.

He promised his wife of 74 years that he’d stop when he reached 500, but he just kept on going. Creating the collection has largely been a solitary labor of love, with long hours spent in the garage making and maintaining the seats. It was only last year that he admitted that he wanted some help.

“I call myself his museum assistant, but he calls me his helper,” says Carye Bye, laughing. She’s a local artist who moved to San Antonio recently from Portland, Oregon, where she ran the Bathtub Art Museum. She helps out a few times a week with opening the museum and keeping regular hours.

“Right now we’re on ‘Project Reglue,’” she says. “Sometimes things fall off the seats and he just puts those things in a catch-all bowl. We’ve restored probably 75 seats so far.”

According to Smith’s detailed records, the museum averages about 1,000 visitors a year. On a recent rainy weekday afternoon, a geocache enthusiast from Fort Worth was surveying the grounds while two women, one local and one from Los Angeles, marveled at the sheer numbers of the collection.

Patricia Fetters, the Angelino, says that she frequently makes “wunderkammer,” or “curiosity cabinet” trips.

“We read about this museum and Barney’s story and we had to come see it,” she says. “It’s amazing. I love folk art. There’s all of this detail captured on a toilet seat. I never expected it to be this phenomenal.”

As visitors look through the two-room garage, Smith is quick to point out toilet seats that are the most special to him. His walking stick will direct you to the seat with a piece of debris from the exploded Challenger shuttle. He’ll point out the toilet seat that came from the private plane of Aristotle Onassis, several seats that serve as a hub for geocachers, and a toilet seat from Saddam Hussein’s palace sent to him by a member of the armed forces.

His mind is still sharp. He can tell you the story behind every one of his seats, which he will do if you get him going. With his advanced age and his body growing weary, he wants to sell the collection. But he won’t just let it go to anybody.

“I want somebody to keep it as a museum,” he says. “I don’t care whether it goes to New York or Kalamazoo, Michigan. Wherever they want to take it, they’ve got to keep it together.”

Smith has fielded several offers, none of which have satisfied his criteria. His recent partnership with Clorox has taken the search national with a website showcasing Smith’s favorite seats. Rita Gorenberg, a public relations associate with Clorox, says that Smith displays a new appreciation for the bathroom.

“We really wanted to share that appreciation with others,” she says. “So Clorox is really trying to find that right buyer for his collection.”

Bye wants to keep it local, arguing that it’s time for someone to step up and give Smith the recognition he deserves.

“My sense is that it’s because he’s an outside artist and visionary,” she says. “He’s a folk artist but he’s not a part of the art scene. He isn’t well known for his art, he’s more well known for the whole picture. It’s the package of Barney and the art that matters more than the art.”

She has put together a small group that is searching for a location in town to keep it free and open for anyone who wants to appreciate an artist who made his mark in folk art.

“If his art, and other art like his, was in one space in San Antonio, people would flock to it,” she says. “It would become huge.”

All of this doesn’t matter to Smith. He just wants to keep making toilet seats until his last day.

“I’ve got ideas running out of my ears,” he says. “I may be making more toilet seats in place of wherever [the collection] goes.”

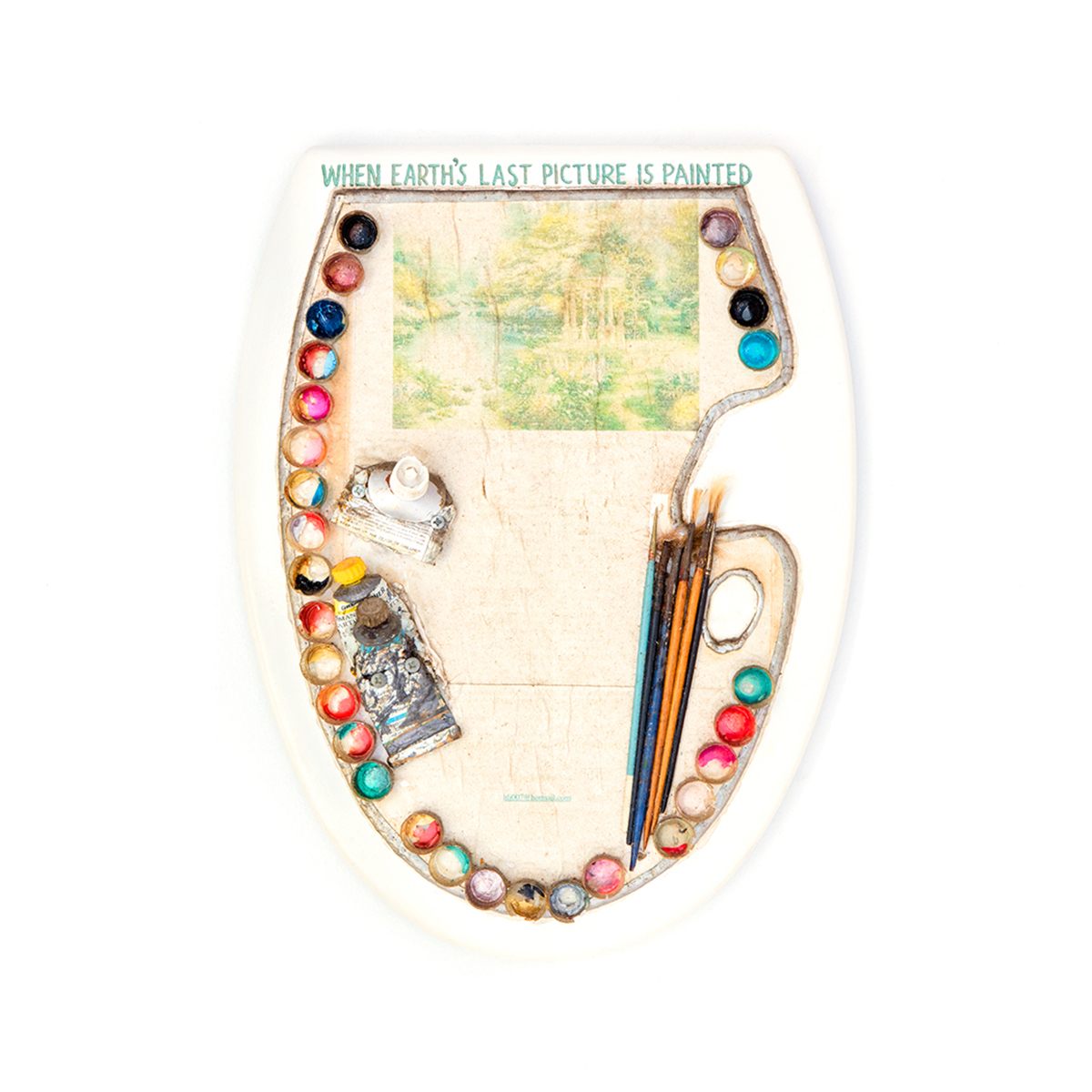

If you ask him about his favorite seat, he shows you something less flashy. Centered on the seat is a piece of paper so worn that its words are unreadable. You won’t have to read it, though, as Smith will immediately recite Rudyard Kipling’s poem, “When Earth’s Last Picture Is Painted,” from memory. He’s known it since it was assigned to him in the fifth grade. The poem describes a world with no critics, where everyone works “for the joy of the working,” realizing their own vision.

“It means a lot,” he said. “I’ll eventually paint my last picture and then I’ll be gone from this old world…And I’ve left quite an impression on a lot of people. Everybody needs their day. I got mine.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook