The Complex Ethics of a Haunted House Starring Psychiatric Patients

A Halloween attraction at a Utah mental-health hospital perpetuated stigmas but benefited residents.

One October morning in 1996, Pat Baker was driving her three youngest kids to school. On the car radio, the zany and irreverent DJ Jimmy Chunga was jabbering about the haunted castle in Provo.

Like everyone in north-central Utah, Baker knew about the castle, which sprung up every October: A spook alley infamous not because it was particularly well-done (though by all accounts it was), or particularly scary (though it was better than average), but because it stood on the grounds of Utah State mental hospital—and because some of the actors who worked there, playing witches and zombies and chainsaw murderers, were patients at the institution.

Baker had been a special kind of shocked to learn about the haunted castle. She directed Allies for Families, a nonprofit that educated parents and teachers about mental health, and provided support for families of the mentally ill. Every day in her work, she had to battle the perception of mentally ill people as unpredictable at best, dangerous at worst. She knew this stigma was precisely why those with a history of mental illness often kept it a secret, lest they make it harder for themselves to find jobs, friends, or housing.

To Baker, the haunted castle only reinforced this negative stigma. But the situation was complicated. Allies for Families contracted with Utah State Hospital, and Baker had a happy working relationship with the hospital administrators. She also knew that the hospital depended on revenue from the castle for its yearly recreation budget. That money wasn’t just an abstract good to Baker—her oldest daughter, Amy, had been an inpatient at the hospital two years earlier.

So Pat Baker had reached an uneasy peace with the haunted castle. That peace wouldn’t last the car ride, however.

From the speakers of her Subaru, Chunga was up to his usual shtick, trying to get groggy listeners to call into his show. This particular morning, the station was giving away tickets to the haunted castle—or, as Baker and her children heard him describe it, a chance to be frightened by “real-life psychos” at the hospital.

As they pulled up in front of the school, Baker’s youngest son turned to her: “Mom, is Amy a real-life psycho?”

That was when Pat Baker decided the haunted castle had to go.

Originally known as the Territorial Insane Asylum, Utah State Hospital was founded in 1885, on an isolated plot separated from Provo proper by swamps and a garbage dump. As the hospital’s website puts it: “The message this reveals about the prevailing attitudes regarding mental illness is unmistakable.”

In 1971, the hospital organized a spook alley for staff and patients, which then became an annual tradition. “Pretty soon the employees here started asking if they could bring their families,” recalls Janina Chilton, a long-time hospital administrator who now runs a museum at the hospital. “It just kept getting bigger.”

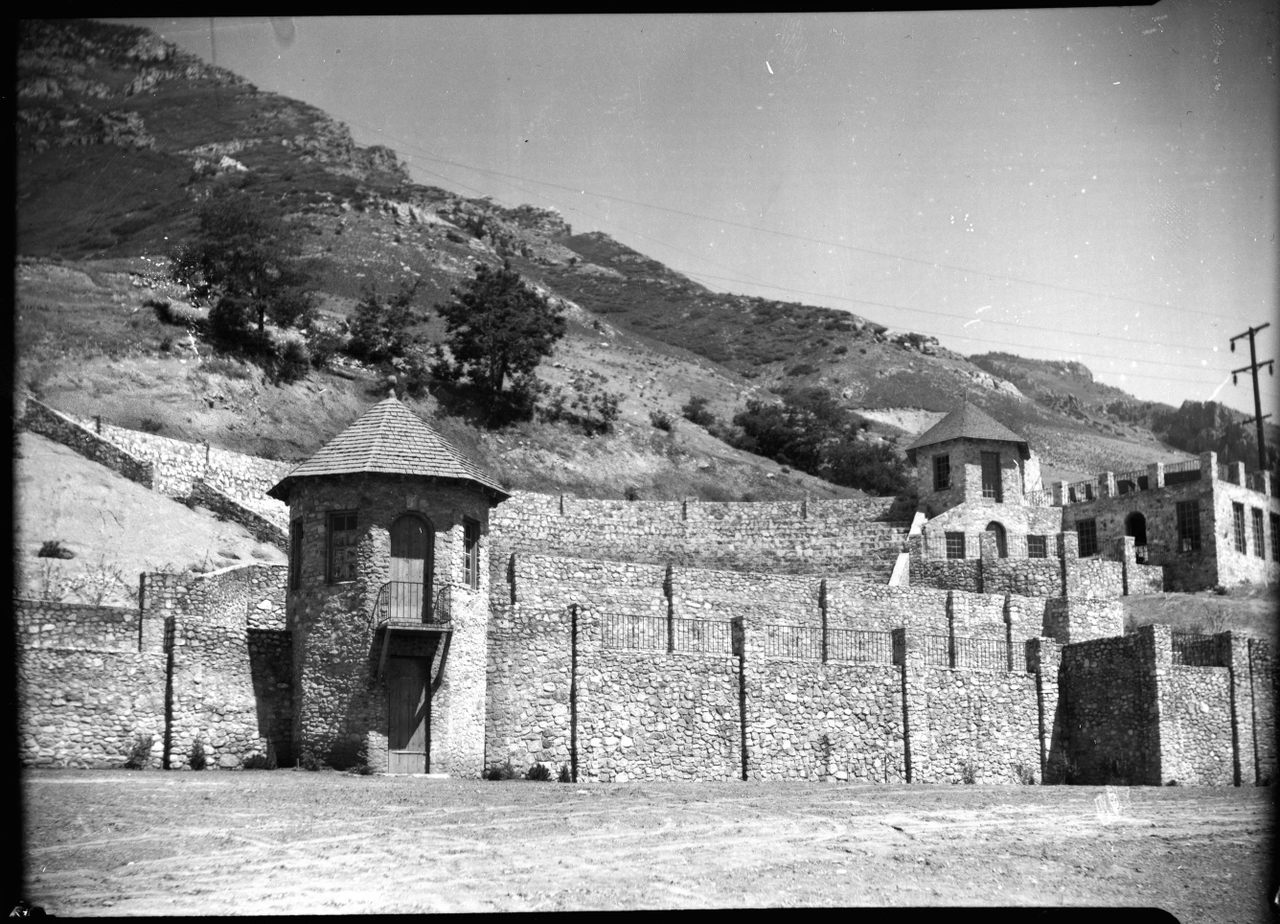

After a few years, the hospital decided to turn the event into a haunted house fundraiser. There was already an ominous building on the grounds that lent itself to the cause: the giant, turreted stone Castle Amphitheater, built as a public works project in the 1930s. Every September, patients and staff would spend weeks working to build and spookify several rooms on the amphitheater structure, each with a unique haunted theme. The castle would open up to the public in late October.

“It was a lot of work,” says Leland Slaughter, director of recreational services at the hospital from 1981 until 2009. “We spent a lot of late nights and extra time doing that.”

Former staff members recall how the patients clamored to help build and act in the castle. Slaughter says that the event was not only therapeutic—a chance for patients to exercise creativity and challenge themselves—but a rare bonding opportunity. “You’d have patients and staff right beside each other that were manning the room. So the patients would get to see the staff in a different light.”

They took the scary factor seriously. Over the years, the castle would include brutal torture scenes and savage gorillas; chainsaw murderers and mad scientists’ laboratories; a swamp monster that popped up to scare people as they walked over its giant water tank. To keep the haunts up to date, a fraction of each year’s revenue would be set aside for new lighting, sound equipment, costumes, and props the following season.

Hospital staff assessed which patients were fit to participate. Those with emotional issues, or whose psychosis might be triggered by the overwhelming lights and sounds, wouldn’t be allowed to interact with visitors. “We didn’t want to interrupt or hurt their treatment at the hospital,” says Slaughter.

Over the years, as the patient population at the hospital became less stable, they relied more on volunteers to don the makeup and costumes. By the 1990s, only 10 to 15 patients were helping at the castle, alongside some 90 citizens from local community and church groups. That didn’t diminish the draw. Attendance at the castle grew steadily through the 1980s, and hit 27,000 visitors a year by 1995. The line extended across the hospital grounds. At $5 a ticket, that translated to $100,000 to $125,000 in revenue.

“State money has lots of strings attached, what you can use it for,” says Chilton—but the castle money was different. “This was all in a separate fund, and didn’t have those same parameters,” she says.

“Over time we became more and more dependent on it, and we actually built the recreation program around the funding,” says Dallas Earnshaw, a longtime staff member and current hospital superintendent.

Indeed, Slaughter says, the haunted castle revenue roughly matched the sum that his department received from the state. They used the money to take patients out to bowling alleys, performances, and restaurants. They bought art supplies, as well as gear for camping, skiing, and river rafting.

“A lot of times, if you got the patients in an outdoor environment, or maybe on a raft, … the patients would open up and talk a little more freely,” Slaughter says. “We were able to do a lot of good for the patients—to show them a sense of normalcy.”

For centuries, there had been a sense of hopelessness surrounding the mentally ill. “The outlook was, ‘They’re gonna be homeless or institutionalized,’” says Baker. Starting in the 1980s, however, she saw that beginning to change—as understanding of mental health expanded, families were no longer willing to simply accept that their mentally ill relatives would be ostracized from society.

“It was a different view of mental illness,” Baker says.

After she heard Jimmy Chunga’s “real-life psychos” comment, Baker got to work convincing others that the haunted castle perpetuated a negative, outdated idea of mental illness. Over the next year, she brought it up at meetings with public officials and fellow advocates. She called reporters on the mental health beat to voice her concerns.

Baker knew that change happened slowly—but she still wasn’t happy when the haunted castle opened up again in 1997. “I do remember being frustrated and annoyed,” she says.

That same year, word of the anti-castle effort made its way to Kat Snow, a reporter for Salt Lake City public radio station KUER. Snow says she immediately understood Baker’s concerns. “I was really stunned that nobody seemed to think that it was perhaps a damaging idea,” she recalls.

Snow decided to produce a radio story to take a closer look at the castle—and to find out if the hospital had good reason to subject its patients to such a spectacle. When she interviewed kids waiting in line for the castle, her microphone didn’t keep them from speaking their minds.

“Knowing that mental people are here is scary,” a young girl told her, giggling.

“It’s real crazy people, not fake!” tittered one boy. “Psycho people! Chainsaws!”

Another girl: “There’s no control over them! They could just grab you and it’d be scary.”

Inside the castle, Snow found a cackling mad scientist, and a man chained to a wall who lurched at visitors as they passed by. To her, these scenes evoked those days when the mentally ill were considered dangerous pariahs. “People were chained to the walls in asylums,” she says. “And here it was being kind of used as a scare tactic.”

(Superintendent Earnshaw insists that the castle planners worked to avoid any scenes that evoked mental illness. “I think it was probably her over-interpreting what she was seeing,” he says of Snow’s reporting. But Snow doesn’t buy it: “I would have a hard time believing that you could do that scene and not know what you’re doing.”)

Snow interviewed a patient named Robin Judd, who was working as a “vampire-witch-creature” in the castle. Judd described how an adult visitor had snarkily asked her if she’d taken too much Thorazine, a drug used to treat symptoms of mental illness.

“It’s not right what the public thinks,” said Judd. “So, the heck with them. If they think they’re going to come see a bunch of freaks—well, they’re not.”

But over the course of the reporting process, Snow’s opinion of the castle began to soften. When she interviewed recreation director Leland Slaughter, she was struck by the sheer amount of money on the table, and how far that cash went towards helping patients feel like part of society.

Snow, who also covered state politics, recognized that the money would not be easy to replace if the castle was closed. “This was a population of people that have been suffering from budget cuts for a long, long time,” she says. “It’s not like the Utah legislature was quick to jump on funding those kinds of things.”

But the question lingered: Did that sad reality justify keeping the castle open?

“By the end, I was really glad I wasn’t the one making the decision,” Snow says. “Because it was a lot more difficult of a decision than it seemed to me at first.”

Not all mental health advocates initially saw the castle the way Pat Baker did. As of October 1997, both the American Psychiatric Association and the local National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI) chapter declined to take a strong position on whether the hospital should shut it down. While they grasped the stigma problem, they also recognized how much money was on the line.

But perspectives were shifting. In April of 1998, a national NAMI representative sent a letter to Utah’s governor, begging him to shut down the “barbaric” castle. The letter read: “I do not know which is more offensive—the fact that this horror show is allowed to continue or that the hospital administrators admitted to knowing that part of the draw each Halloween is the public’s fear of mental illness.”

Later that month, Baker walked into a meeting of the state Board of Mental Health, which oversaw Utah State Hospital. The Board had agreed to make a decision on the haunted castle. As the meeting began, Baker was optimistic—and afraid.

“This is it,” she remembers thinking. “And if this doesn’t work, then it’s probably not going to work.”

When it was her turn to speak, Baker played a recording of Kat Snow’s radio story. She wanted the Board to hear how the children in line talked about the castle. “I knew if there was gonna be a tipping point, that was it,” she says.

Baker herself was interviewed in the story. The Board listened to the recording of her holding back tears as she talked about her daughter: “When you have a family member who has a serious mental illness, and you love that person, and you watch them struggle, and you watch them succeed, it is hurtful to have that person stereotyped as some kind of a maniac.”

Representatives from the hospital also had a chance to weigh in before the Board voted. Administrators explained that they were actively working to combat the stigma issue. “We took advantage of the notoriety of the castle to educate the public about stigma,” says Earnshaw, who was present at the meeting. Every October, hospital staff and patients would visit local schools to explain to students that the mentally ill were just like them. “It was an opportunity for us to educate the community,” says Earnshaw.

The hospital staff said as much to the Board. And, of course, they reiterated the revenue issue—nobody in the room was confident that state lawmakers would allocate more money to fund the recreation program.

The Board took a vote. It wasn’t unanimous, but they reached a majority decision: It was time for the haunted castle to close.

As far as controversies go, the haunted castle controversy had been intensely civil. Baker continued her relationship with the hospital for many years after the final haunted castle in 1997. “We didn’t have any ill feelings towards her,” says Earnshaw.

Historian Janina Chilton suspects the castle’s days were numbered regardless of the Board’s decision, simply because the event was becoming a larger legal liability. Chilton, Earnshaw, and Slaughter all say that they sympathized with Baker and her concerns about stigma.

For her part, Baker would ally with the hospital to lobby for state funding to replace the castle revenue. In 2000, the legislature moved around money to appropriate an additional $76,000 to the recreation program, and the hospital was able to continue its robust recreation program.

In many ways, it was a happy ending. The stigmatizing castle had been vanquished, and the patients were no worse off.

Yet the end of the castle signified a broader change—something that went beyond one hospital or one haunted house.

Your average Utahan might say it was an explosion of political correctness. In 2006, the Utah Valley Daily Herald published an editorial blaming “politically correct zealots” for the castle’s closure, and imploring Utah State Hospital to bring it back. To this day, Earnshaw gets calls every year asking him to revive the event. (It’s a non-starter—stigma aside, all of those elaborate lights and costumes are long gone.)

Hospital staff say it was a loss of trust in the people of Provo. Earnshaw thinks that a handful of insensitive radio DJs didn’t accurately represent the community’s view of the mentally ill, and that advocates like Baker had fixated on that minority. “Most of the public were actually quite offended that people would assume that they would stigmatize the State Hospital because of the castle,” he says.

Pat Baker, on the other hand, believes that it represented a newfound demand for dignity, particularly among people like her, who saw their loved ones being publicly stereotyped. “I had been in Utah for a while and knew about this haunted castle, but it wasn’t until it hit me personally that I was willing to take it on,” she says. “I knew it was the right thing to do.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook