Vintage Photos of Lumberjacks and the Giant Trees They Felled

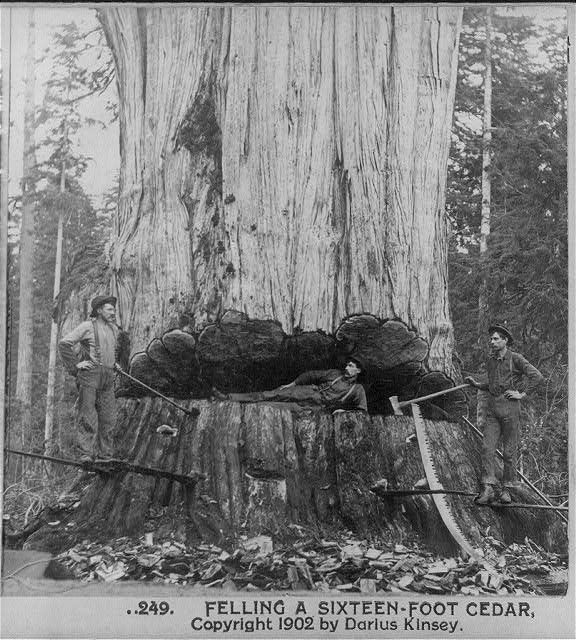

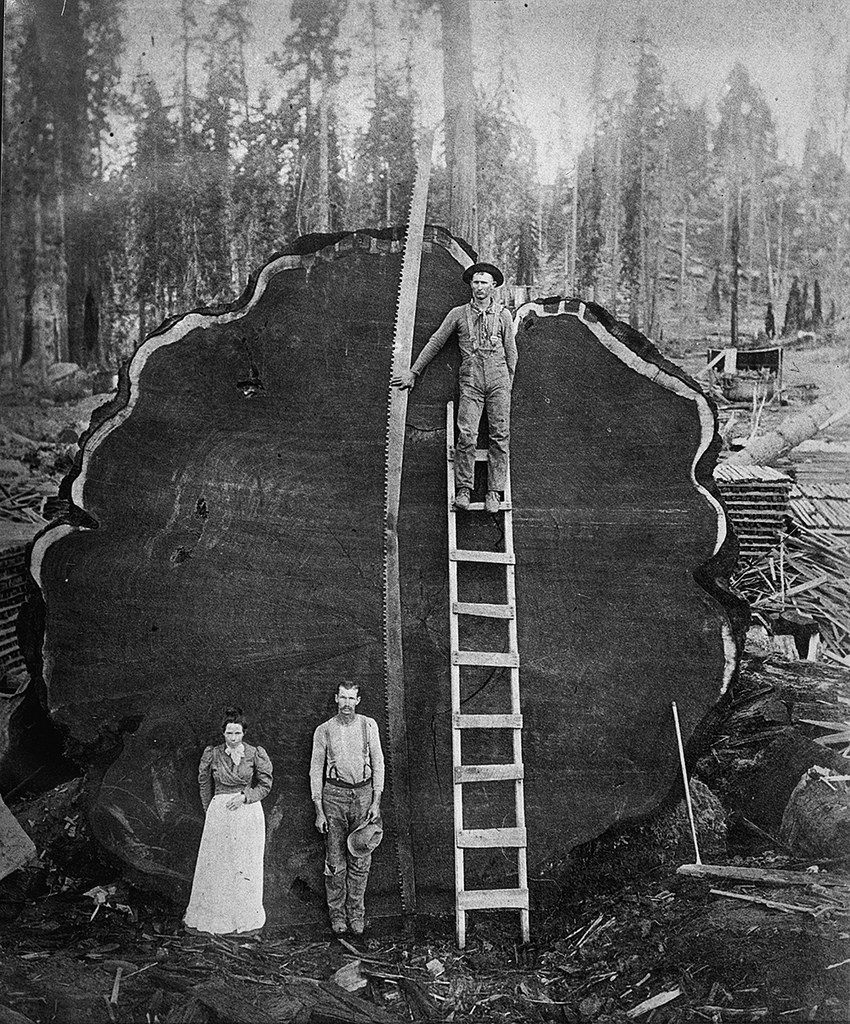

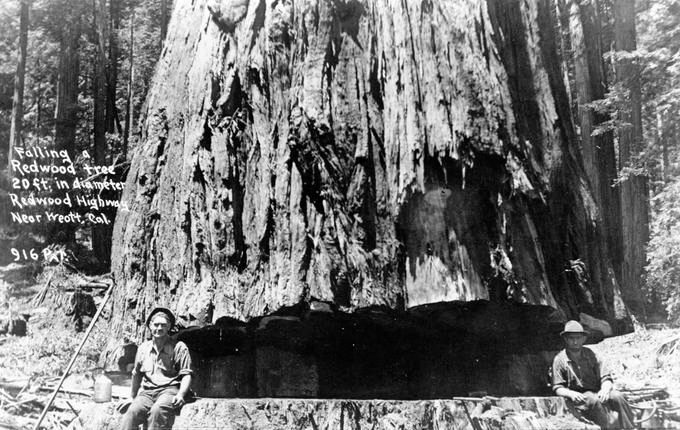

Loggers posing with the trees they cut down by hand.

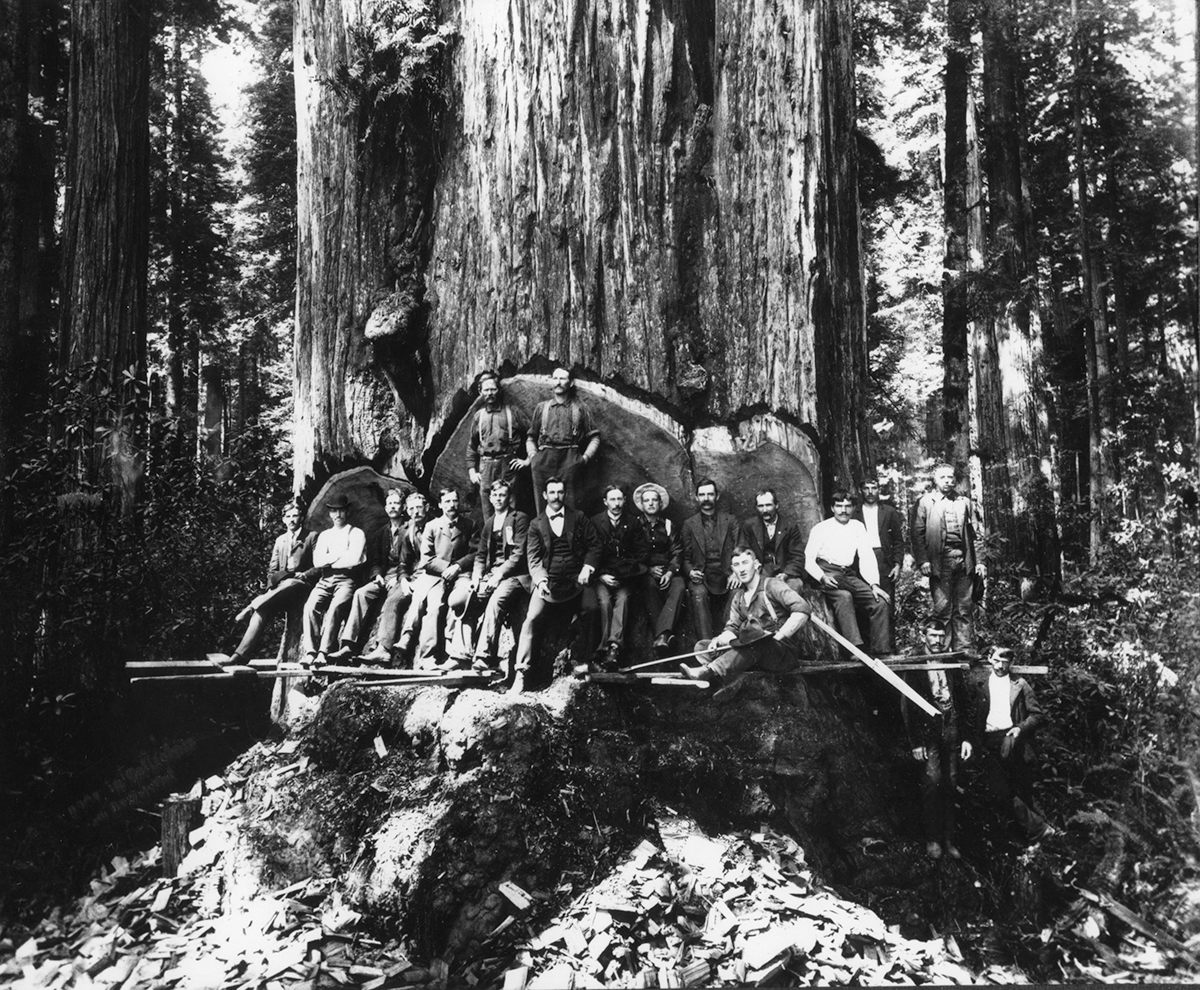

Loggers among the redwoods in California. (Photo: Ericson Collection/Humboldt State University Library)

The Pacific Northwest and California are home to some of the largest trees in existence. A giant sequoia, for example, grows up to 311 feet; a coastal redwood, up to 370. Diameters range from between 16-20 feet, but can grow as much as 30 feet. Just trailing is the Sitka spruce, which averages between 120-180 feet in height. These behemoths existed for thousands of years, and were known within the local American Indian communities, before the lumber trade arrived in the 1800s.

And the lumberjacks realized, way before selfies, that these trees make for amazing photo ops.

The logging industry grew throughout the 19th century. By 1910, it was the largest employer in Washington State. At the forefront were the loggers, the men whose job it was to fell these enormous trees by hand. Their work was dangerous and labor-intensive: in the early 20th century, an estimated one in every 150 loggers died.

Typically, the loggers would stand on a springboard, which was slotted into notches in the tree above the base. Using crosscut saws and axes, the loggers would then work on chopping a wedge into the tree. It was important to judge the direction of the cut for where the tree would fall. For a redwood, it was preferable for the tree to fall either towards water or up a hill, to prevent splitting the timber.

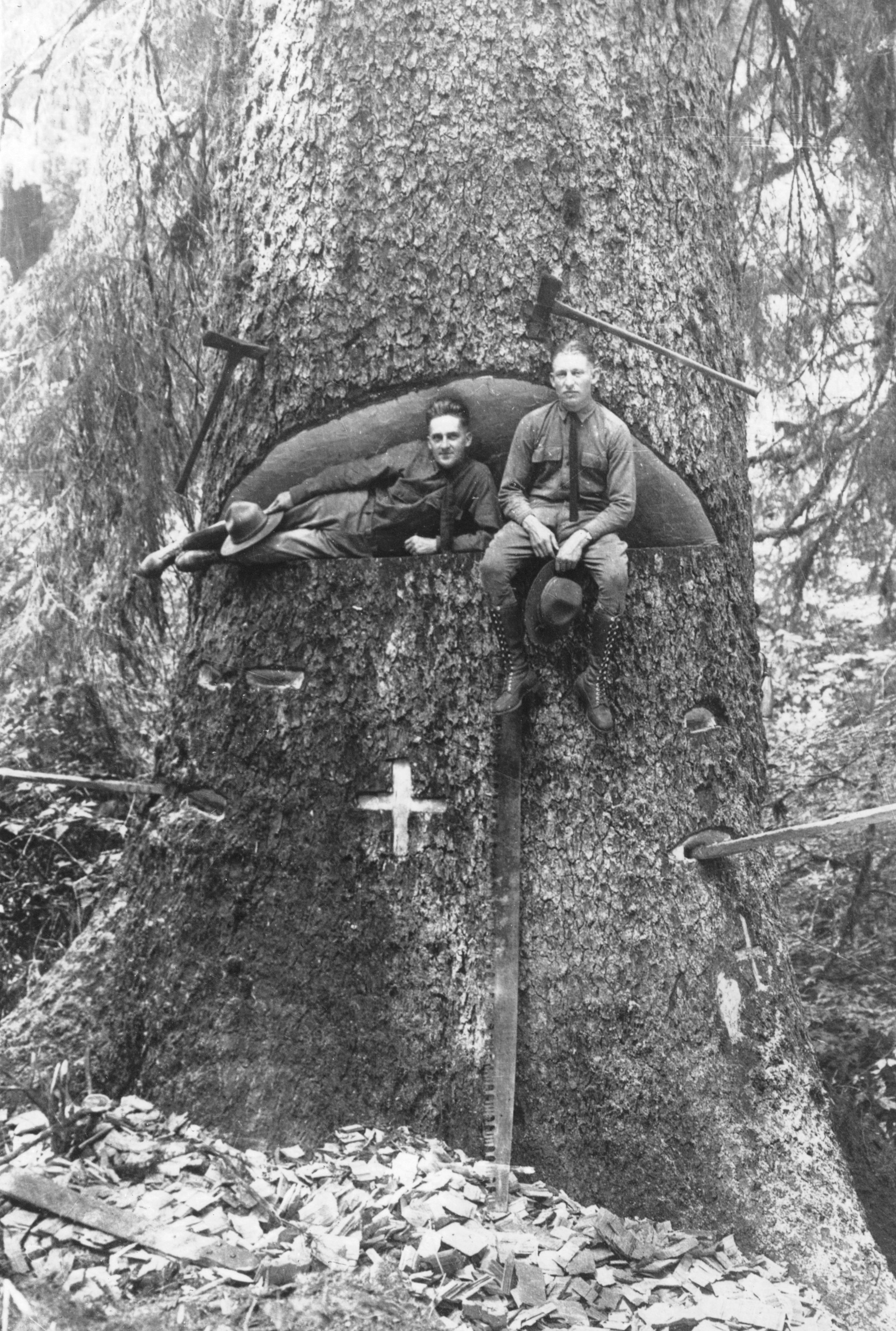

Tree logging wasn’t just for trade. In 1917, the Army established the Spruce Production Division to supply lumber from spruce trees for WW1 aircraft, and by 1918, there were just over 28,000 men working within the division. From this also grew a union, the alliteratively-named Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen.

Within all this is the tragedy that, despite the difficulties of the work, the logging industry succeeded in destroying a vast number of ancient trees. By 1900, an estimated one-third of old forest redwoods had been destroyed; by the 1960s, that figure stood at 90 percent.

Some of this work was documented in photographs. Here, an extraordinary collection of images of loggers posing inside a cut tree, or gathered around a trunk as big as a house.

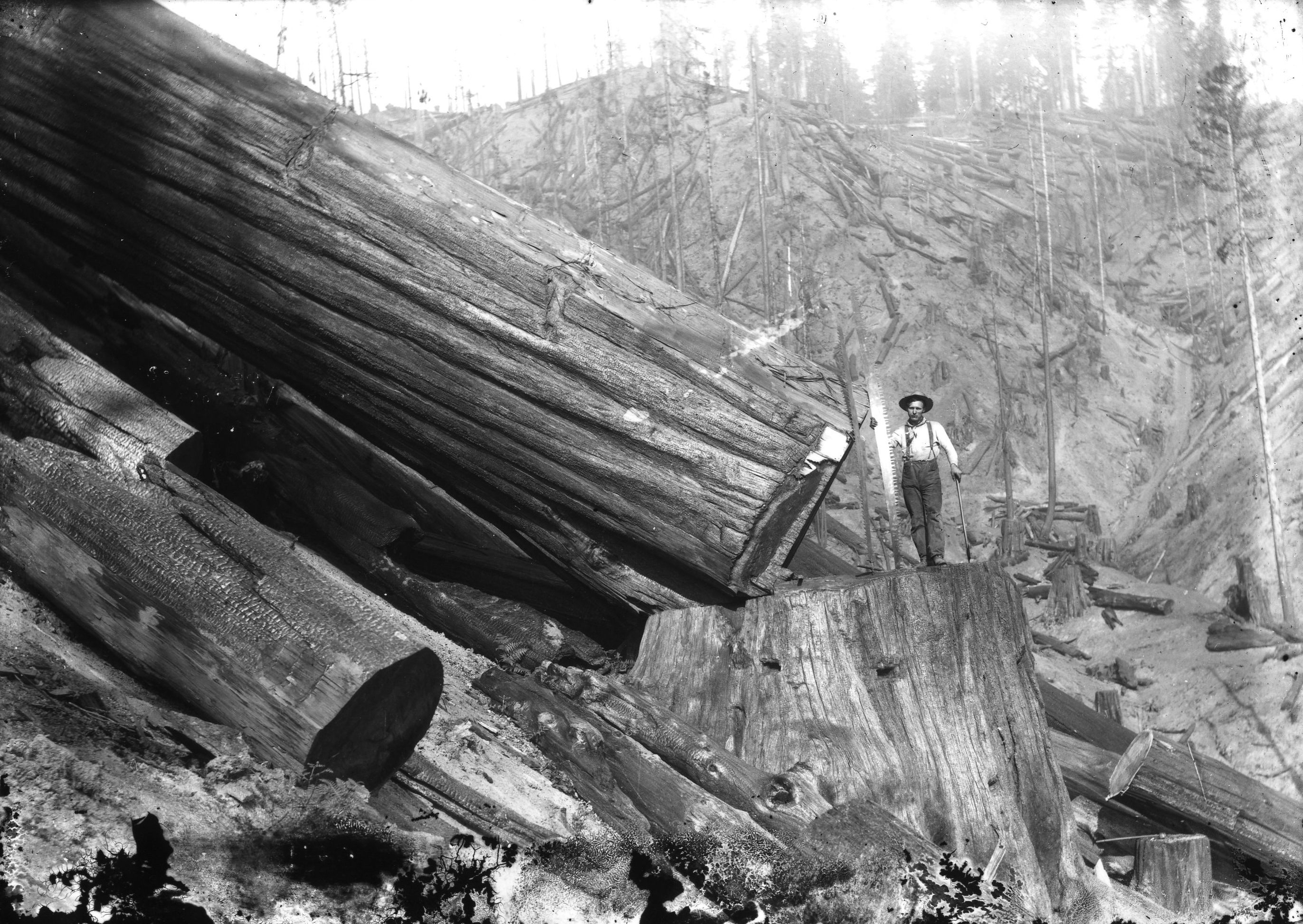

Standing by a Sequioa log in California, c. 1910. (Photo: Library of Congress/HAER CAL,54-THRIV.V,2–17)

Members of the Spruce Production Division sitting in a giant Spruce tree in Oregon. (Photo: Gerald W. Williams Collection/OSU Libraries Special Collections & Archives Research Center)

A logger stands on a felled spruce tree, c. 1918. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-73909)

A group of men standing on a Spruce tree stump. (Photo: Gerald W. Williams Collection/OSU Libraries Special Collections & Archives Research Center)

Loggers with a Redwood 20 feet in diameter. (Photo: Gerald W. Williams Collection/OSU Libraries Special Collections & Archives Research Center)

Loggers with felled trees. (Photo: Gerald W. Williams Collection/OSU Libraries Special Collections & Archives Research Center)

In the redwoods of Humboldt county. (Photo: Ericson Collection/Humboldt State University Library)

A logger with a redwood. (Photo: Swanlund-Baker Collection, Humboldt State University Library)

A felled Sequioa tree in California, c. 1900. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-105050)

US Army Spruce Division solders sitting on a stump, c. 1918. (Photo: Gerald W. Williams Collection/OSU Libraries Special Collections & Archives Research Center)

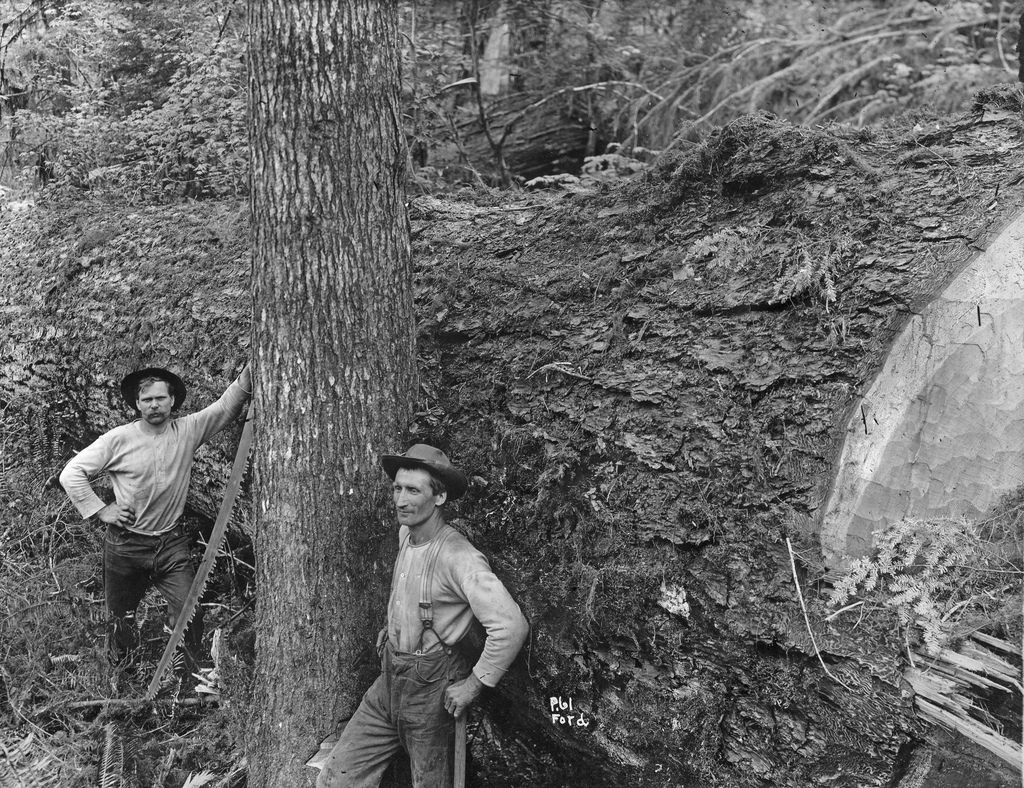

Two loggers with a felled tree. (Photo: Gerald W. Williams Collection/OSU Libraries Special Collections & Archives Research Center)

Loggers on a Cedar stump near Deming, Washington, 1905. (Photo: NARA/95-G-195968)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook