The Most Unlikely Man to Influence A Generation of Writers: Walking Stewart

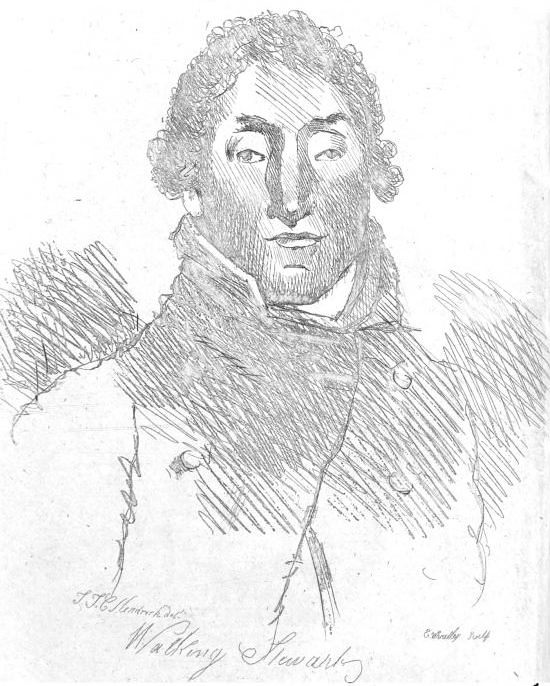

An etchng of Stewart from this 1822 biography ‘The Life and Adventures of the Celebrated Walking Stewart’ (Photo: Public Domain)

In their time, the English Romantics were known as a motley crew of libertines and dope-fiends. Percy Shelley was expelled from Oxford for an essay defending atheism, Samuel-Taylor Coleridge spent most of his life strung out on opium and Lord Byron (who was first deemed “mad, bad and dangerous to know” by his lover, Lady Caroline Lamb) died while fighting for Greek independence.

Like the multifaceted characters in George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones, their lives wavered between moments of heroism and scandal. In her diary, discovered in 2010, Claire Claremont, a lover of both Byron and Shelley calls the men, “monsters of lying, meanness, cruelty and treachery.”

But who influenced this oddball generation of writers, who produced works of literature like The Rime of The Ancient Mariner and Frankenstein? Their irrational behavior was partially a rational reaction to the industrialism that were ushered in by the Enlightenment era. The Romantics sought the sublime in everything: praising spirit, nature and the classical past with impassioned poetry and prose. And sometimes they found the sublime in a person, as was the case with their least-known, most-unexpected influence—a half-mad Englishman named John “Walking” Stewart.

William Wordsworth in 1798 (above) and Samuel Taylor Coleridge (below), who co-wrote ‘The Lyrical Ballads’. (Photo: Public Domain)

(

(

Photo: Public Domain)

Walking Stewart redefined eccentricity. Something like a cross between Jack Sparrow and Dumbledore, Stewart had the gift of gab and a bohemian fashion sense (he preferred dressing in raggedy “Armenian”garb, which mainly consisted of military accessories that he’d acquired in his wanderings). According to his biographers, Stewart walked across continents, venturing as far Tibet and Arabia. His geographical expertise even earned him entrance into the Royal Society. Thomas de Quincey, author of Confessions of An English Opium-Eater, was so impressed by the man that he wrote an article about him which was published in The London Magazine in 1823. Some parts read like an eulogy for the greatest explorer of all time:

“His mind was a mirror of the sentient universe.–The whole mighty vision that had fleeted before his eyes in this world,–the armies of Hyder-Ali and his son with oriental and barbaric pageantry,–the civic grandeur of England, the great deserts of Asia and America,–the vast capitals of Europe,–London with its eternal agitations, the ceaseless ebb and flow of its ‘mighty heart,’–Paris shaken by the fierce torments of revolutionary convulsions, the silence of Lapland, and the solitary forests of Canada, with the swarming life of the torrid zone, together with innumerable recollections of individual joy and sorrow, that he had participated by sympathy– …I however, who am perhaps the person best qualified to speak of him, must pronounce him to have been a man of great genius; and, with reference to his conversation, of great eloquence.”

The full account of Stewart’s life is no less extraordinary. His adventures kicked off in 1753 when, at the age of 14, he joined the British East India Company as a clerk in Madras, India. After he left the company in 1765, he was captured by Sultan Hyder Ali and forced to work as an interpreter and soldier in Mysore. When the sultan, suspecting that Stewart would try to leave the kingdom attempted to have him assassinated, Stewart fled to Arcot, where took up residence with Muhammad Ali Khan Walla Jah, an associate of the British East India Company. Stewart was employed by the noble until he saved up £3000. At this point, according to “a Relative,” he:

“…took leave of India, and travelled over near the whole of Persia and Turkey on foot; rarely allowing himself the indulgence of a horse or caravan…”

By the time he arrived in Europe in the 1770s, Stewart had developed into a full-blown free spirit and vegetarian. Stewart’s spiritual philosophy was one of “feeling” materialism; he denied the soul’s existence, but he believed that atoms could be sentient without having any level of memory-based cognition. In Paris, between 1790 and 1792, Stewart made a strong impression on the Romantic poet William Wordsworth, then in his twenties. Wordsworth, who would eventually express a similar naturalistic philosophy in his writings, went on to become become one of the leading members of the first generation of Romantics, co-writing The Lyrical Ballads with his friend Samuel-Taylor Coleridge in 1798.

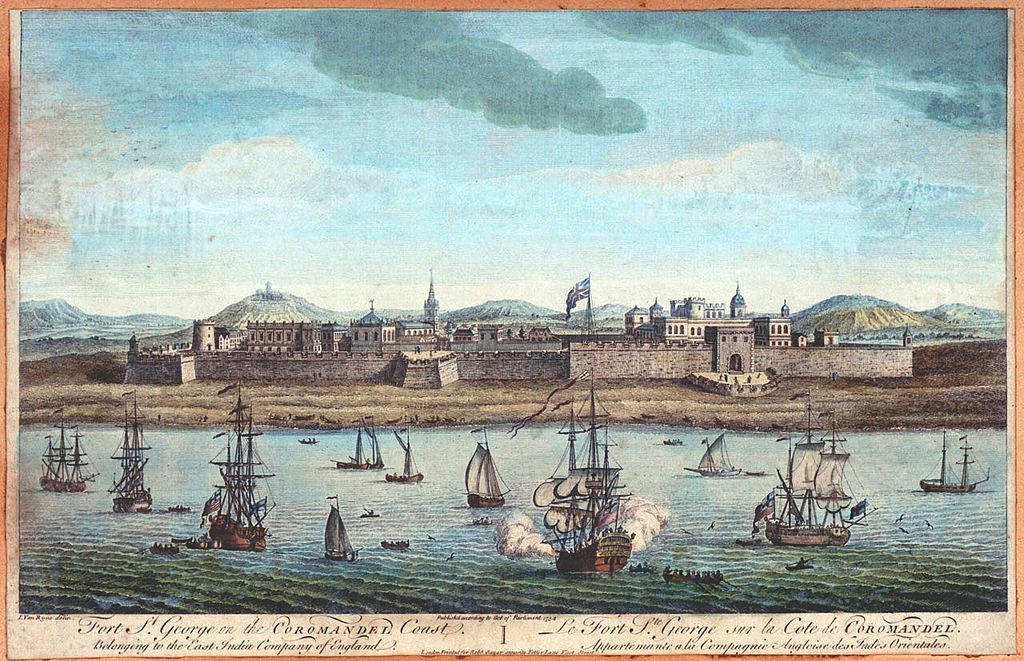

A painting of Fort St George in Madras (Chennai) by Jan Van Ryne, 1754, one year after Walking Stewart joined the British East India Company (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

At the turn of the century in London, Stewart hung out in coffee rooms near Piccadilly and meditated in St. James Park. He lived a spartan lifestyle until he was awarded at least £10,000 in unpaid salary from the East India company. With his newfound affluence, Stewart established his own “Epicurean apartment” on Cockspur Street, where he hosted fancy dinners and entertained guests with conversation. Although the self-acknowledged sage wanted to be remembered and revered for his teachings, he grew increasingly skeptical about society’s future. Henry Salt, writing in an 1849 essay writes:

“He seems to have been haunted by a constant dread of some great and world-wide revolution, some ‘universal empire of revolutionary police terror,’ which would ‘bestialize the human species and desolate the earth.’”

Stewart’s solution to the coming Apocalypse was simple: People needed to create secret societies of book lore:

“…he recommended to all those who might be impressed with a sense of their importance to bury a copy or copies of each work properly secured from damp, &c. at a depth of seven or eight feet below the surface of the earth; and on their death-beds to communicate the knowledge of this fact to some confidential friends, who in their turn were to send down the tradition to some discreet persons of the next generation; and thus, if the truth was not to be dispersed for many ages, yet the knowledge that here and there the truth lay buried on this and that continent, in secret spots on Mount Caucasus–in the sands of Biledulgerid– and in hiding-places amongst the forests of America, and was to rise again in some distant age and to vegetate and fructify for the universal benefit of man…”

An engraving of Queen’s Palace, St James’s Park, in 1810, where Walking Stewart was said to meditate (Photo: Public Domain)

An engraving of Queen’s Palace, St James’s Park, in 1810, where Walking Stewart was said to meditate (Photo: Public Domain)

It’s not known whether Stewart went forward with his literary time capsule project before his death in 1821, but at the very least, his itinerant and cosmopolitan lifestyle may have had some effect on the early Romantic movement in England. Many members of the second generation (Shelley, Byron) probably never met him, but they lived like him, wandering across Europe and rebelling against Western social norms. Like Stewart, their actions were impulsive and heartfelt, and their works helped to inspire Gothic writers such as Edgar Allen Poe and Aesthetes like Oscar Wilde.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook