Walldogs and the Disappearing Art of Painting Signs on Buildings

Factory building of the Bloch Brothers Tobacco Company, on Wheeling Island, West Virginia. (Photo: Library of Congress)

When the tall, lean 39-year old from Chicago was asked to explain his job, he said: “If anybody asks you, sign-painting’s just an occupational disease. But we get around, that’s something.”

It was the mid-1930s, and the Works Projects Administration was assembling a Historical Records Survey–personal accounts about different professions–as a kind of oral history of American workers. They sent writers out to scour the country, hoping to create a portrait of its workforce. They interviewed all kinds of people, including a few sign-painters like the man from Chicago.

At the time sign-painting was a fairly common job, and many sign-painters did, indeed, get around. While most cities had their own sign shops, many smaller towns and rural areas depended on traveling artisans to do their sign-painting.

We can see the chipped and faded remains of many of these signs today, often called “ghost signs”, apparitions from a time before computers and vinyl letters. Because they had to be made on the spot, every sign was produced with a brush attached to a hand. And if the sign was big enough and painted high on a wall, that hand was attached to a “walldog”.

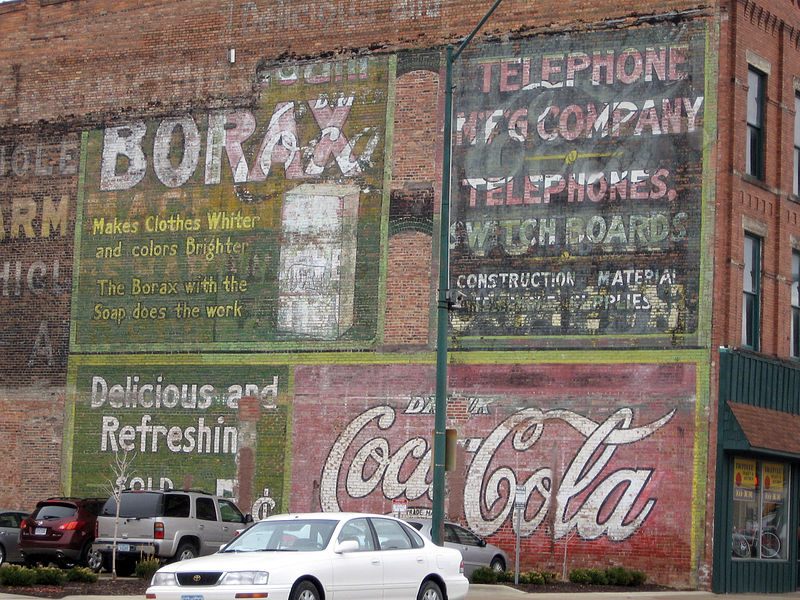

Ghost signs in Fort Dodge, Iowa. (Photo: Billwhittaker/WikiCommons CC BY 3.0)

For the high-wire act, walldogs scaled buildings to paint signs that sold everything from the local laundry to King Midas Flour to Owl Cigars. It’s not exactly clear where the term originated, but it goes back at least to the turn of the 20th century. And it stuck. The workers were called walldogs for two reasons: first because they worked like dogs (you try painting a 30-foot brick wall in the blazing heat or wind and cold); plus, sliding up and down the side of a building meant they needed to be tethered–leashed, so to speak–to the wall.

The signs may have been commonplace, even ordinary, but there was nothing ordinary about a walldog’s skill or their influence on our landscape, even if it was unintentional. Despite being the low men on the sign-painters’ totem pole, they were landscape artists, uncredited but combining the skills of a muralist and a rock climber. They were often poorly paid, and living more than a little dangerously. Not only were the designs and execution done by hand while hanging from the side of a building, the paints themselves were “personal” formulas, each artist mixing his own slurry of toxicity.

Old Dr Pepper mural on a building in the town of Hico in Hamilton County, Texas. (Photo: Library of Congress)

That Chicago sign-painter wasn’t kidding about it being an “occupational disease”: the paints, especially wall paints that needed to outlive more than a few winter storms and blasts of summer sun, were typically a combination of linseed oil, pigments, “driers” like benzene or gasoline, and most importantly for the paint to last: lead. Lots of lead. Sometimes buckets of powdery “white lead” (a lead complex used as a base for both white pigment and smooth texture). As one sign-painter told the WPA Survey about a particularly large sign: “… we used a ton of lead just for the period.” As toxic as the paints were, it is primarily the lead that has kept many ghost signs from disappearing altogether.

The United States first became a carnival of signs around the end of the 19th century, when advertising took hold like never before. Back then, there were no rules about signs–where or how big they could be, or how much valuable wall space they were allowed to take up. Commercial buildings, barns, depots, grain silos: any place people gathered or traveled past (by train or buggy or, a little later, by auto) was fair game. These ads tended to be simple: uncluttered copy, easy to read and, as important, easy to repaint.

Part of an old Mail Pouch Chewing Tobacco sign on a wall in downtown Grafton, West Virginia. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Businesses like groceries and drug stores began to advertise for themselves right on their own buildings. If they were lucky, they might get a company to pay for the “privilege” of including the store name in the ad. These were attention-getters, and as more and more businesses became national and signs began to spread across the country, the names Dr. Pepper, Beechnut or Borax became as prominent on the sides of buildings as the names of your resident druggist or greengrocer.

The 1920s, 1930s, and 40s saw the “golden age” of wall advertising, with companies like Coca Cola and Mail Pouch Chewing Tobacco taking up lots of vertical real estate. But as quickly as they spread, beginning in the 1950s, they began to disappear. Electric signs and eye-catching neon were the hot new thing; large-scale printing of vinyl signs soon meant you didn’t have to pay a sign-painter or maintain the paint; and in the 1960s there was President Lyndon Johnson.

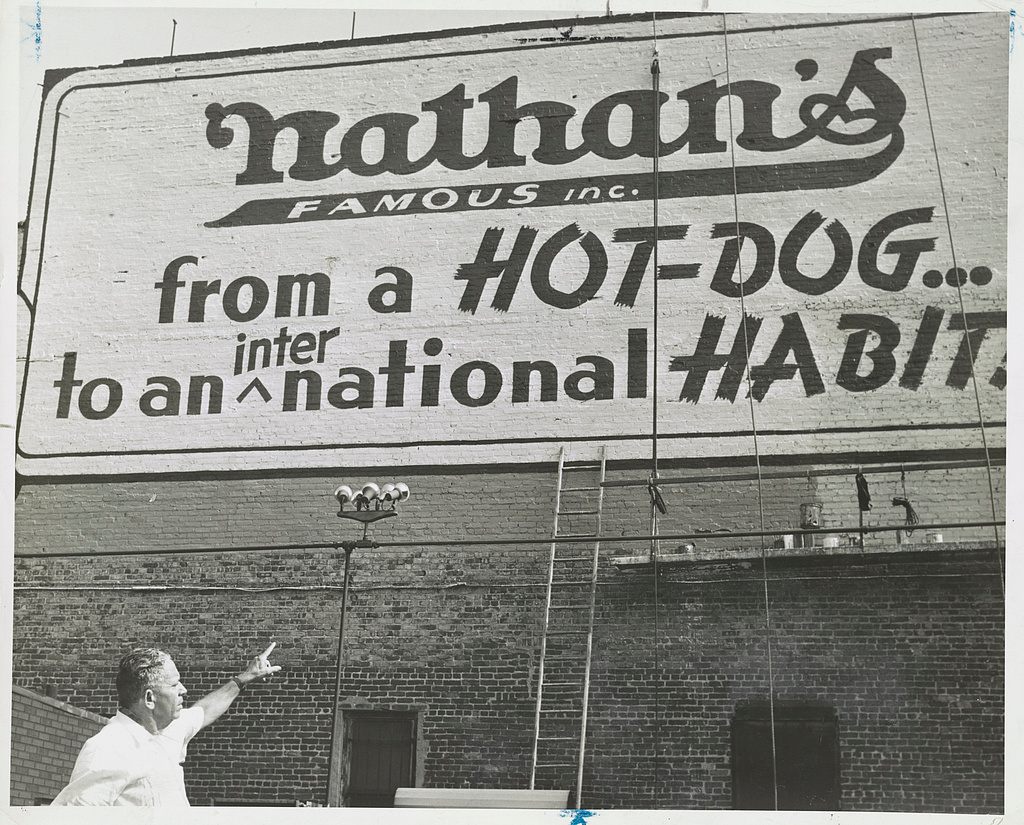

Photograph showing Nathan Handwerker pointing to Nathan’s Hot Dog sign. (Photo: Library of Congress)

In 1965, Johnson signed the Highway Beautification Act, regulating road signs that were popping up along the growing interstate system. There had been an earlier attempt to control the signs–the 1958 Federal-Aid Highway Act–and although the two pieces of federal legislation were aimed at highways, they paved the way for local regulation of outdoor ads and signs in many communities, restricting where they could be, their size, and sometimes even their colors.

The signs and their painters began to fade from view, neglected, painted over or stuccoed through the years, leaving only a ghost of themselves behind, worn by time, weather and a little apathy.

Cambridge, Ohio. (Photo: Joanna Poe/flickr)

These days many towns and cities are bringing the old signs back to life by documentation, preservation and restoration. And in recent years, sign-painting has experienced something of a revival on the fronts and walls of new businesses. There are now sign shops and collectives celebrating the craft, mentoring new converts, mixing their own paints (minus the lead), and reminding us that the touch of the artist’s brush can’t be replaced by vinyl or neon.

While the term “walldog” may have been derogatory way back when, it has now been embraced in this resurgence by a new breed of high-flying sign-painters, proud to be Walldogs.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook